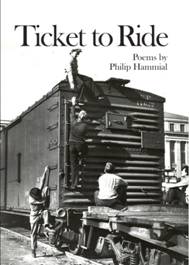

Ticket to Ride by Philip Hammial

Island Books, 2015

It’s so terribly apt that Philip Hammial begins his twenty-seventh collection of poems, Ticket to Ride, with an epigraph from Thoreau’s Walden:

I desire to speak somewhere without bounds; like a man in

a waking moment, to men in their waking moments; for I

cannot exaggerate enough even to lay

the foundation of a true expression.

Ticket to Ride is a collection of life-moments; a certain ‘true expression’ splash in a muddy world puddle, some shocked morsel of life momentarily caught in the light. They aren’t easy moments, perhaps, but they are strangely beautiful, nonetheless.

It’s hard to imagine what the creation of a collection of this size and gravity at this point of Hammial’s long and energetic career as a Detroit-born Australian poet must feel like. A few poems in, and my main question becomes, ‘doesn’t he ever get tired? Where on Earth, or any other planet, does he keep finding these images?’ To any reader, Ticket to Ride must feel like an escalating journey through a smashed galaxy of images, oftentimes disparate, sometimes frighteningly homogenous. To borrow that perhaps over-used phrase from Alejo Carpentier, the work might be an intelligent exploration of lo real maravilloso, which could make sense, considering Hammial’s professed love of Cuban literature. Yet the work can’t so easily be framed inside any easy point of reference. This latest instalment from the ‘wunderkind chronicler’ is, as the book’s title claims, a ride. And a ride suggests play or danger, suggests journey, not destination.

Having purchased the ticket, going along for the journey with Hammial is no simple task, and in fact what you thought might be a pleasure cruise turns out to be a ten-cent tent show, fraught with well-dressed little horrors, gilt with holy icons that could be balloons with faces drawn on them, evoking the sense of ‘an annunciation made by a somewhat suspect/ New Age angel.’ Reading Hammial, both in this new collection and throughout the years, the reader could at times be forgiven for feeling utterly out of depth and flailing about in metonymic phrases seemingly so disconnected as to be deliberately misleading. While no reader would dare assume that the central voice in a poem is the poet speaking from real life (whatever that is), Hammial leaves one believing in authorship and legitimacy, regardless. We are sucked in to the quirky narrative, dragged along down a ‘dark ally,’ willing participants in what could be the ultimate tomfoolery, perhaps even something more sinister. As ‘Hold your Breath’ asks: ‘On tippy-toes across a log, will the ballerina reach dry/ land before the crocodile wakes up?’ Reading Ticket to Ride, we become that ballerina.

It might be neat and tidy to assume this collection centres around ‘an old man/ dreaming about the good old days.’ Yet this is impossible, as in the brilliant poem, ‘Honour,’ we hear, ‘talk about the good old days. I’d/ rather not.’ More likely, we have been tricked into thinking this book is a log pile of typical tropes like nostalgia and longing when really it explores the vast, near-violent open spaces of that ‘wunderkind’ brain whose sole purpose is to display: ‘my library/ stacked against you.’ In short, we have doubtless been fooled, and left with the sneaking suspicion that we were always going to be. And just as we are ready to ingest it all, the poet warns: ‘Don’t eat that, it come up/ from underground’.

Reading, sometimes reeling, through the collection, it would be tempting to assume that there is no axis mundi in this chaotic world. And yet the essential tempting idea of clarity persists, insisting that it is not so difficult to locate inside the miasma. This is not surrealist writing, no matter how overtly it might toy with the genre. There is precision here, a thousand sparkling truths caught inside what could be biography, sometimes autobiography, and oftentimes play-acting. It reads like Hammial has made good on his threat to ‘invoke Literary Canon.’ How terrifying. Big things are questioned here. ‘Tomorrow be Glory? – that spiel ain’t real.’ Ticket to Ride explores a very human grappling with sex and ageing and death, and the pull of religion, even spirituality, if I dare call it that.

Fans of Hammial will cherish this latest extravaganza for all its deliberate trickery, the sense that what we all think it might mean is planets from the essential star. As one of the poems claims: ‘It’s a very heavy book.’ Readers new to this fringe-dwelling yet somehow central figure of Australian poetry will find something to marvel at here too, awed by the sense that nobody, perhaps especially the poet, minds what we make of it all. As Hammial says in the collection’s final poem, ‘Hey Bra, You Like My Beat,’ ‘Niko you’re responsible/ for this mess; you can clean it up I’m out of here.’ And just in case anyone fears it’s all clever trickery that nobody feels responsible for, here’s a beautiful and honest ‘waking moment’ from what curiously turned out to be my favourite poem, ‘A Journey’:

And now they begin to pull things from pockets, purses, bags — matches, bottle caps, cigarette butts, train tickets, keys, combs, pencil stubs — “things,” says George, “that you’ll need for your journey into our world.” And now, diminished, like my friends only a few inches tall, a huge hand picks me up, places me gently into the empty box and closes the lid.