Poems of Olga Orozco, Marosa Di Giorgio & Jorge Palma

Edited and translated by Peter Boyle

Vagabond Publishing, 2017

In 2017, Vagabond Press launched its Americas Poetry Series. This is a brave and much needed venture, one that borders on the quixotic: an Australian editor offering publications from poets from the Americas to the Australian reading public, for the love of poetry and the art of translation. So far, the series has three excellent entries focused on the translation of Spanish language Latin American poets into English. Notably, all three books in the series consist of translations by translators who are themselves poets. They seize the creative potential of the translating act, producing poems that walk the fine-line between the languages and cultures of the original and the translated texts, while seeking to conserve the imagery, expression and rhythm of the poems. Given that many of the translations published so far stem from the baroque to the vanguardist schools of poetry, it is no small feat that the books present readable, engaging translations that retain the playfulness, the shock, the allure and ambience of the originals. Though this review concerns the first publication in the series, it must be noted that it has continued successfully, with the two latest publications being Poems of Mijail Lamas, Mario Bojórquez & Alí Calderón, focusing on a selection of Mexican poetry (reviewed in these pages by Gabriel García Ochoa), and the haunting Jasmine for Clementina Médici by the Uruguayan Marosa di Giorgio, with a foreword by notable poet, translator and academic, Roberto Echevarren.

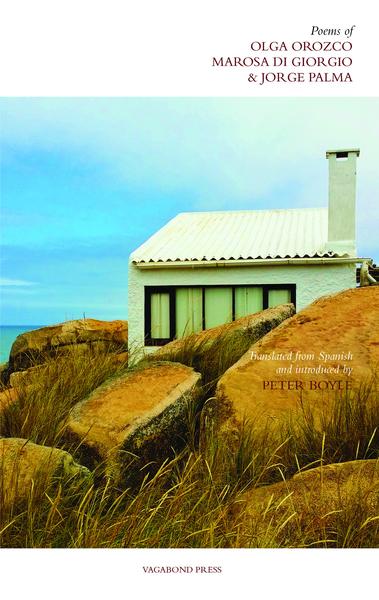

Poems of Olga Orozco, Marosa Di Giorgio & Jorge Palma is selected and translated by Peter Boyle and consists of a selection from these three poets from Argentina and Uruguay. Boyle is himself a distinguished Australian poet and translator, with a long-running relationship with Latin American poetry, having previously translated poems by the Cuban José Kozer and the Venezuelan Eugenio Montejo, amongst others. Adorned with a beautiful photograph of a Uruguayan cottage taken by fellow Australian poet Stuart Cooke, that, with its ochre and blue tones, accentuates the connections between these distant souths (Australia-South America) and offers a glimpse of idyll that connects with the romantic tendencies of some of the contents. Yet, acting as the proverbial calm before the storm, this idyll also presages the turbulence of the pages to come. That is because Boyle’s book provides an eccentric, alchemical, if not iconoclastic selection that chooses the path of discovery, adventure and mysticism. To aid the reader, Boyle provides an excellent introduction that serves to not only to introduce the poets, but also contextualises the work of the three poets by placing them in their respective poetic traditions. Boyle’s introduction also addresses the task of translation itself, presenting different difficulties in each of the three cases. However concerned Boyle may be about those things that are lost in translation (rhyme, sound play), his anthology presents a delightful set of translations that read well, and most importantly, represent three different twentieth century conceptions of the poetic in Latin America: those who took up the call of surrealism, represented by Olga Orozco; the neo-baroque and experimental, in Marosa di Giorgio; and the conversational, socially engaged poetry in the poems of Jorge Palma. These are three forking paths that lead into different traditions that are well worth exploring.

The book begins with a selection of poetry by Orozco (1920-1999), and whose poems are carefully chosen from a lifetime of poetic practice, including a poem dedicated to her dead brother Emilio, dating from 1946, to the poet’s last verses, published posthumously in 2009. Orozco’s ‘Cartomancy’ sets the tone for what is to come, with its dense and dreamlike images and allusions to the world of the magical. In Orozco’s poems, this is a world where both poet and the reader are subjected to the twists and turns of fate and are surrounded by its symbols, often as jarringly juxtaposed as the twists of fate itself. Orozco was involved in Argentina’s Tercera Vanguardia, a vanguardist movement that drank heavily from the well of surrealism, embracing its formal experimentation and tendency to the violent juxtaposition of incongruent imagery. Perhaps, however, the most marked influence from the surrealists in Latin America was its play with the unconscious and its trust in dream imagery. Orozco takes from these traditions and filters them through images, experiences and places from her own past. As a result, there is in Orozco’s poems a marked tendency towards the magical and the fantastic. According to Boyle, Orozco’s faith in the magical stems from her own childhood through the figure of her grandmother who inculcated her with a belief in the magical and in the talismanic, in symbols, herbs and indecipherable turns of phrase. Orozco’s poems embrace these elements and render them on the page in the service of exploring her own recurring themes. There is in all of her poetry a fascination with both the fantastic and the fatalistic that is coupled with an exploration of the poet’s interior worlds. These are worlds marked by nostalgia for long-gone people and places of the poet’s past: the Argentine Pampa where the childhood home once stood; death; the animal-world, and the spaces once inhabited. Notably, many of Orozco’s poems are dedicated to the dead, ‘For Emilio in his Heaven’, ‘Pavane for a Dead Princess’ and ‘Cantos a Berenice’ are dedicated to her dead younger brother, to Alejandra Pizarnik and to Orozco’s cat. Orozco’s recurrent themes lead the poet to her own images and symbols of the plains, the elements of nature, the seasons, dogs, talismans, stones and snouts that “steal your breath”. Orozco puts these images to use to create a multifaceted image of reality, characterised as a space ruled by fate; a space in which one must attempt to decipher the runes of chance. Orozco explores this dynamic in ‘Mutations of Reality’:

Like me a captive, with constellations and ants,

perhaps inside a glass ball where souls wander,

I’ve seen reality shrink and take the form of puny Jonah

inside the whale

or endlessly expand into that skin which, in a stream of

vapour, breathes out all the sky:

indissoluble stowaway groping through the bilge water of the

unknown

or all-encompassing beast at the moment of exploding

against the wire fence around limbo […]

Like me, protector of one of destiny’s indecipherable masks,

Reality dresses up as a witch and with a sigh transforms

dazzling birds to legions of rats,

or puts all of yesterday’s and tomorrow’s wine in a pot to

evaporate