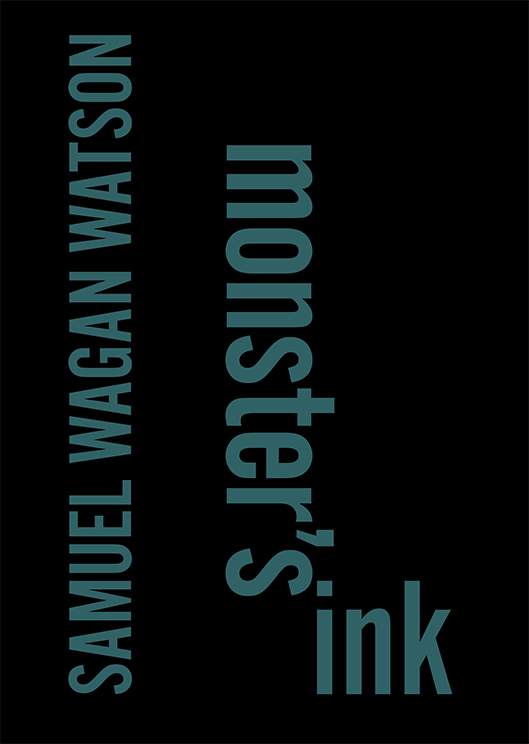

Monster’s Ink by Sam Wagan Watson

Recent Work Press @ IPSI, 2016

Selfless by Zoe Dzunko

The Atlas Review, 2016

Since the late 1970s Warren Motte, Professor of French and Comparative Literature at the University of Colorado, has been collecting mirror scenes in literature, a studiously archived assembly of ‘moments when a subject glimpses himself or herself in the mirror.’ From an analysis of these more than 10,000 scenes collated in Mirror Gazing (Dalkey Archive Press, 2014) Motte suggests that in such instances ‘a curious effect of dissociation seems to be at work, for the face in the mirror typically presents itself to the subject with its otherness prominently on display’; the reflection becomes ‘the deforming mirror of another’s gaze.’

As the title suggests, monsters in many forms populate Sam Wagan Watson’s latest chapbook, Monster’s Ink, the third in IPSI’s chapbook series after Philip Gross’s Time in The Dingle and Katharine Coles’s Bewilder. Wagan Watson’s monsters are hidden in the darkness of closets and beneath beds – or they’re not hidden at all, proudly occupying positions of power. Many of the monsters, like Wagan Watson (of Munanjali, Birri Gubba, German and Irish heritage), are culturally diverse: a German vampire, Jenze Stager, with a taste for Aboriginal Dreaming; Bram Stroker’s Dracula evoked somewhere under a bed in Brisbane; a ‘7-foot arachnid-homo-species from a rare alabaster egg’; an indigenous equivalent of Mary Shelley’s creation, Frankenstein of the Dreamtime.

There is another folkloric monster in this ink, one that appears by implication, and not appellation as such: Bloody Mary, who will appear in a mirror when her name is said before it three times. The ghostly catoptromantic apparition, often bloodied, can be malevolent or benevolent, and prophesies visions of the future. It is as though, with the many I’s that litter Monster’s Ink, Wagan Watson has summoned himself into the mirror for honest inspection and reflection. In the tellingly titled ‘Butterflies And Premonitions’ he writes:

I was born with a bad headache and before I could write I predicted the wording of incident reports before accidents occurred […] Pulling into the driveway an empty house sleeps […] And before my key hits the front door I know what lies beyond. I picture this scene while switching off the igni tion in the car […] answering my stomach’s want, for butterflies and premonitions …

Like Wagan Watson’s most recent full-length collection, Love Poems & Death Threats (UQP, 2014), the majority of the poems in Monster’s Ink are haibun, a form of prose poetry traditionally comprising a paragraph or so accompanied by a haiku addressing or distilling the entry’s themes and content. Love Poems & Death Threats opens with ‘Blood and Ink’, which begins: ‘“I AM A RIVER …” / How your words reverberate off the mirror of our conscience.’ The possibilities of the plural pronoun – a river’s tributaries; Wagan Watson and the reader; etc – are numerous, but dominant amongst them is the idea of many selves, and reflections as a means for addressing these. Later in that collection, the water-like Wagan Watson again finds a mirror:

The bedroom mirror can only reflect the serene skin of a lake; a lake is an ephemeral living entity, and the mirror will remain a dead-pool in the bedroom. (‘Warning’)

So what is discovered in this time spent before the mirror? We could begin with a survey of some of the many I’s mentioned above. ‘I was born in a land, borne from a Dreamtime …’ begins the first poem in Monster’s Ink, ‘Wonderland?’ Wagan Watson continues later: ‘I am free but have few democratic rights. I am the unforgiven scourge of the Ruling Class.’ In ‘A Brief Biography (Standard Operating Procedures #1)’ he once again introduces the mirror as a means for making and managing a self: ‘I am 175cm tall with a width that fluctuates seasonally. I live in a house with many mirrors as opposed to a domicile of glass that will only canvas certain reflections.’ One such reflection is Jenze Stager, first given voice in ‘Die Dunkle Erde [The Dark Earth]’, Wagan Watson’s opera with Stephen Leek, performed in 2004 with the Australian Voices Choir and special Dijeridoo arrangement by William Barton. Stager is a reflection of Wagan Watson’s mixed German and Aboriginal heritage; the German vampire finds his ‘black reflection / lost, I thought too / forgotten, forgotten / in the countless nights.’

The fruits of Wagan Watson’s introspection are not only reflected in mirrors or slick surfaces, but also in the revised versions of older poems. ‘Monster (Reloaded)’ is an updated version of a poem originally performed at the 2007 Utan Kayu International Literary Biennale, Indonesia. It is here that we find Wagan Watson as Frankenstein’s monster:

I am one of Tony Abbott’s monsters, hiding under his bed … I think like his version of a monster, therefore I am, Frankenstein of the Dreamtime … I scare some white people with my English, and some black people too, I am Frankenstein of the Dreamtime.

‘Love Poem (Reloaded)’ is an updated version of the ‘Love Poem’ in Love Poems & Death Threats, in which the protagonist ‘no longer used his real name, just the combination of slugs, LOVE POEM’ from his tattooed fists. In the reloaded version: ‘In time and in all the accumulated violence, he forgot his real identity, and only travelled with his signature-combination of slugs.’ The inapposite paradiddle of punches is extended, and a haiku appended to the violence:

The hardest stones crack

in the weighting pains of time,

destiny so cruel

It is not just the prose poetry that makes this slim 28-page collection seem disproportionately dense, it is also the proliferate population of possible Wagan Watsons that occupy the pages.