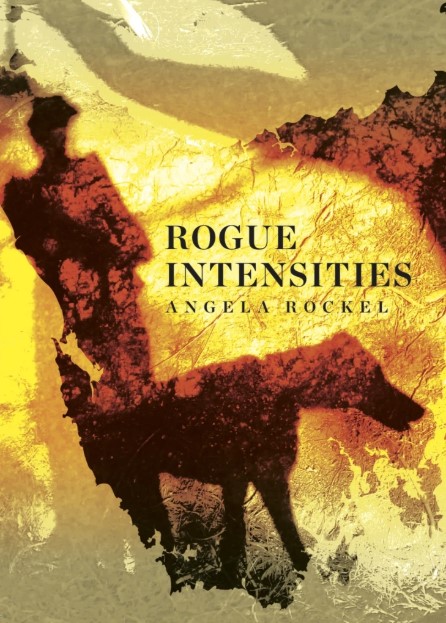

Rogue Intensities by Angela Rockel

Rogue Intensities by Angela Rockel

UWA Publishing, 2019

It’s January. As I begin to write this review it’s over 40 degrees celsius outside our small non-air-conditioned house in inner suburban Sydney. I’m indoors, perspiring lightly, with a desk fan on, windows closed, blinds drawn, listening to wails of gusts of hot wind. In Melbourne some of the international tennis competition matches have been closed. It’s been raining mud there. Canberra airport has been closed. There is thick smoke and nearby fire and runways are needed for water tanker aircraft. Friends in Bundanoon in the Southern Highlands, who have already been evacuated three times during recent bushfires, are on ‘Watch & Act’ alert as a fire a few kilometres from their place has reared up again. In the context of these extreme climate-changed conditions I’ll attempt to ignore my anxiety and temperately address Angela Rockel’s Rogue Intensities, though I know that the intensities I’m talking about presently are more commonplace than rogue.

Angela Rockel’s book is a journal of place. It’s a contemplative, highly literary diary documenting five of her more than forty years of observations and experience of living in rural Tasmania. Evolving from blog posts and structured almanac-like by Gregorian calendar, described as ‘moving month by month across five turns of the solar year’, the book works its entries through connection with nature, history, terrain, mythology, philosophy, family, farming, community as well as involving several international locations. Rockel says that she ‘bears witness to this place as I attend to it’.

The title is taken from a line by US anthropologist and ethnographer Kathleen Stewart – ‘Rogue intensities roam the streets of the ordinary’. Rockel’s introduction explains ‘a rogue intensity’ as a moment of potent feeling when an object provokes a brief, acute response, for example, being suddenly stopped in your tracks by a leaf animated by sunlight or the particular colours of an insect. Not so much ‘the streets of the ordinary’, these entries already seem less banal because of their location in terrain where ‘the ordinary’ is the complex superdomain of a rural biota.

Originally from Aotearoa, in the early 1980’s Rockel settled on her husband’s farm in fire country on the Huon River in south eastern Tasmania. Her husband is identified as T throughout the journal. His antecedents were ticket-of-leave settlers from Tipperary, Ireland. His great grandfather was a convict transported to Van Diemen’s Land in 1853 for stealing sheep. T’s great grandmother arrived as an indentured servant. In the late 1850s the emancipated and by then married couple was granted the parcel of land on which T and Rockel now live.

Wild fire has long been part of the area. Only a few pages in, in a climate-altered summer month of January, there is the realisation that Aboriginal methods of land management with fire have been disregarded since colonisation. T and Rockel’s old farmhouse had burnt down in 1981, from a chimney cinder, not a bushfire. She writes looking out on a thicket of deciduous food forest ‘in a provisional reprieve’ from catastrophic climate change and knowing ‘a lick of burning air could still flick down from the red centre and take us out’.

Natural flora and fauna are documented in precise detail, in lists, and significantly, in description of their return once, half a century ago, T had stopped the old practice of cutting regrown trees for box timber and also ceased dairy farming, leaving the land to grow as forest.

One autumn, walking through the forest’s undergrowth Rockel and T look up to see a Wandjina cloud spirit blown in from the Kimberley that as they move closer morphs into a large tall masked owl. The bird is injured. They wrap her in a shirt and take her to a local raptor rescuer. He thinks the bird has been hit by a car. He places her in a box to rest and, possibly, recover. Worried that the bird might not live Rockel spends the night fretting.

At times her language seems quaint and a little anachronistic, as if from earlier times. She has already written in this entry that she is ‘restless and heartsore and full of dread’ on hearing that a friend, M, in Aotearoa is sick.

Perhaps she should have killed the owl. She philosophises about damage and death, unintended suffering inflicted on both humans and creatures ‘and to communities and cultures’. The rescuer reports that the bird has grown stronger in the aviary. A year later, although not free, it’s surviving well and is being visited by a wild male masked owl. Rockel sees the wounded owl as having ‘somehow presaged’ M’s death and that leads her into a meditation on loss and love. Then she muses on her family’s story that their last name onomatopoeically means owl ‘somewhere in the forests of Northern Europe, up near the Baltic Sea’.

Rockel takes her ‘foreignness to the foreign place of my maternal ancestors in Ireland who had left a place scoured and ruined by nineteenth century famine’ to emigrate to Aotearoa. The visit to the old stone farm house outside Bantry, an area ruined by conquering English land grabbers (here named only as ‘landlords’), is unsettling. Until then she had regarded her dispossessed relatives as ‘virtuous escapees’ to Aotearoa but now (quote ‘here be monsters’) she reflects on the complex idea of ownership and the unease of living herself on unceded Aboriginal land in Tasmania.

‘Bearing witness’, she records dire situations like that of the critically endangered swift parrot on Bruny Island. She investigates ocean heat as a prime effect on climate change in scientific articles. There are many instances of lists that form a kind of personal biological taxonomy. There is coverage of research into toxoplasma and zoonoses like the lyssa virus transmitted from fruit bats to humans. There are notes on the inventive Scottish road builder John McAdam. There is the care of dairy cows that Rockel tends and milks. There is a daughter’s grief when her mother dies – and renewal – in a return to Aotearoa, via Christchurch, ‘the quake-shattered city’. To share the strangeness of her mother’s absence with her sisters, without overstating, the topics here are wide-ranging and the book is of substantial length.