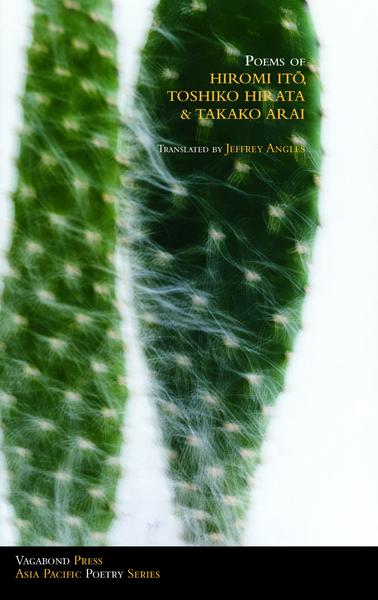

Poems of Hiromi Itō, Toshiko Hirata & Takako Arai

Translated from the Japanese by Jeffrey Angles

Vagabond Press, 2016

In the winter of Pokémon Go, I read quite a few new books of poetry. The collection Poems of Hiromi Itō, Toshiko Hirata & Takako Arai was the most cogent. These three Japanese poets are taboo-breaking women who write without reservation about ‘female experience’ in the political context of contemporary transnational capitalism.

There was a long tradition of separating literature from politics in Japan which fostered rarefied or, what translator Jeffrey Angles, in his invaluable introduction calls ‘staid, polished and artsy’ language. Eschewing tradition, Hiromi Itō, Toshiko Hirata and Takako Arai take a contemporary approach via dialectical sensitivity to the way poetry might sound and rhythmic direct speech. Sometimes this technique produces incantatory repetition, especially in Hiromi Itō’s shamanist poems.

Hiromi often addresses once-sensitive subjects like female eros, post-partum depression, sexual desire and inequity. Her poems are confronting. There’s a room of deformed and diseased body parts preserved in bottles in her poem from 1991, ‘Father’s Uterus, or the Map’ –

The men pointed to testicles with elephantiasis Those are my father's bones and spinal column Those are my father's joints Those are us, the children our father gave birth to The men pointed to foetuses with hydrocephalus And that is you The men pointed to a breast with cancer And that is my father's uterus The men pointed to a uterus that had grown teeth

Hiromi Itō moved to California in the early1990s and now lives in both Encinitas, near San Diego, and Kumamoto, on the Southern Japanese island of Kyūshū. Some of her poems, like ‘Mother Dies’ examine expatriate identity, the future of children born to Japanese expats and the sense of not belonging in either country –

I had thought my own existence was certain But now I understand Things are indeterminate, colors and shapes Things are indeterminate, even sounds Is it an /I/ or an /r/? It all makes sense now It is not just a problem with me but with all Nikkeijin1

In ‘Yakisoba’ Hiromi recounts a confusing exchange in a supermarket with an old expatriate Japanese woman who shouts and yells out to promote the yakisoba (fried noodles) she is selling. The poem ends –

Here is a woman Who comes back alive, who comes back dead Who connects with the next woman With tens and hundreds and thousands of women With generations, dozens of generations down the line

Toshiko Hirata, together with Hiromi Itō, Matsui Keiko, outsider poet Shiraishi Kazuko, and others, is well known in Japan as a major figure in what was called the ‘women’s poetry boom’ of the 1980s. (Though, apparently, Hiromi Itō was not too impressed by the ‘boom’).

Toshiko Hirata uses irony and repetition to make poems that are deeply sceptical of relationships, of the strictures of society, of the normative family, and of poetry itself. Many of her poems are quietly and darkly sardonic.

In a recently published collection, The Freedom of the Joke, Toshiko considered small objects like staples in intimate contrast with the immense force of the disastrous earthquakes, tsunami and aftershocks of 2011 –

Some of the documents that came today Were fastened with beautiful staples The color of dayflowers For me who had known nothing but gray staples Their color was fresh and new (‘Beautiful Staples’)

Just two weeks after the disasters Toshiko published ‘Do Not Tremble’ in the daily newspaper Yomiuri Shinbum (The Japan Times) . It was a poetic plea to the earth to stop shaking so that everyone could return to their ordinary lives –

It is March, it is spring It should be a gentle season of vernal sleep When one sleeps so deeply there is no dawn But spring this year Shakes us to keep us From falling asleep Earth, it is enough For you to simply Keep spinning happily Leave the trembling To windblown flowers and Laundry hanging in the year You should simply spin Innocently

Eleven years younger than Hiromi and Toshiko, Takako Arai (born in 1966) is the daughter of a manager of a now-obsolete small traditional silk weaving factory in Central Japan. In early work Arai wrote about women textile workers. She moved to Tokyo for her education and lives there still.

Like Toshiko, Takako responds poetically to the ongoing consequences of the nuclear crisis. Her experimental and socially critical poetry uses repetition, direct speech, fragmentation and combined imagery. Her ironies are complicated. For instance, she uses euphemistic phrases like ‘womanly shadow’ for women’s genitals. (Jeffrey Angles’s extensive notes on the poems are essential to grasping the levels in all three poets work.)

Takako’s connection with the now redundant craft-textile industry remains a topic. In ‘Colored Glass’ a factory occupies a young woman’s body when she swallows a silkworm –

I swallowed it!

The eternal silkworm

On its mission forever

Crawling through the labyrinth of my bowels

The bitter worm squashed in my teeth

...

There is a factory floating like an isle inside

Its head turns round and round

Recently, a friend of mine visiting Sydney from Adelaide, where there is no Uniqlo (yet), made a shopping excursion to the Japanese global clothing shop. I had just read Takako Arai’s poem railing against corporatisation and this particular company’s threat to individuality. (I am wearing a Uniqlo blouse as I write this review – and I am repentant). Uniqlo’s recent expansions are seen, by capitalists, as bringing economic hope to Japanese business in the aftermath of the 2011 disasters. Not so for Takako Arai –

I'm sick of it

all this Goth clothing, all this Uniqlo-ing

...

Isn't that all you'd ever let us wear?

Wasn't that our national uniform?

Before the quake

The tsunami of the recession

All we ever worried about?

...

The reactor building about to fly off (buttobō)

Embankments (teibō), conspiracies (inbō), ministerial offices

(kanbō),

Unbelievabō

Incredibō

TEPCO2

Puts on their Uniqlo

To bulwark

The tsunami

('Galapagos'3)

As well as introducing new poems, this collection gathers work from various periods of publication by these dynamic women poets. It offers further complexity, exuberance, depth, variousness and challenge than I have canvassed in this brief review but my aim has been to give due attention to this startling and straightforward contemporary Japanese poetry.