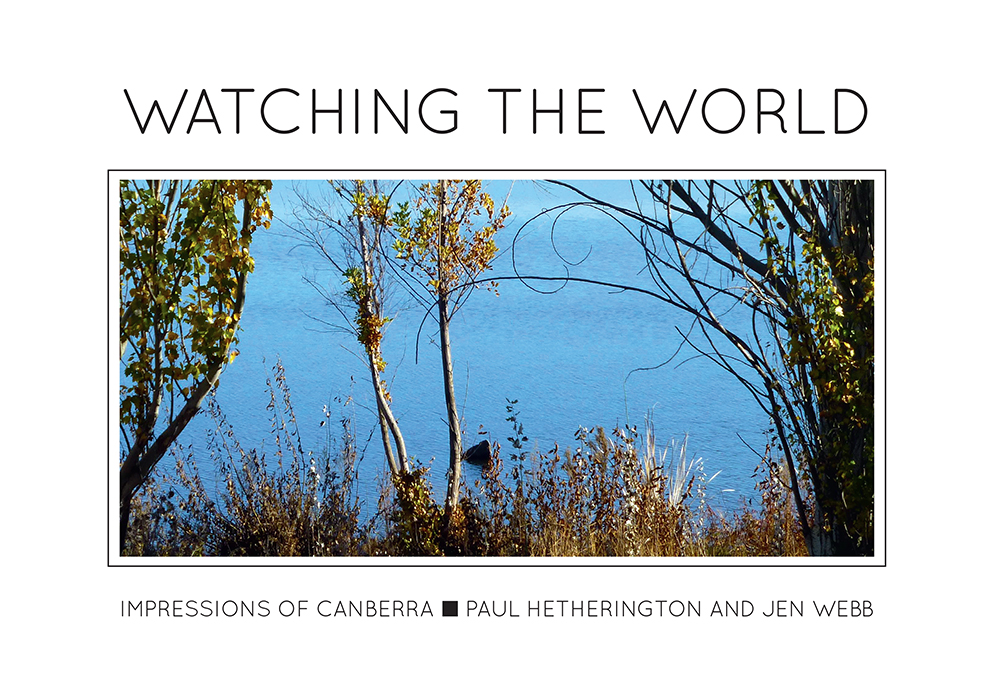

Watching the World: Impressions of Canberra

by Jenn Webb and Paul Hetherington

Blemish Books, 2015

What is it about Canberra that invites so many definitions? Comparing where we live with where we don’t is an Australian fixation, but there’s a specific energy to the way that people with a connection to Canberra go about this – they will start deriding or defending the place minutes after you’re introduced.

At least, this is my own tendency as someone born and raised in Australia’s ‘big country town’ capital. Like a family member, Canberra is mine to love, mine to hate, and mine to define. It was with this prickly attitude that I opened Paul Hetherington and Jen Webb’s Watching the World: Impressions of Canberra – the end result of a collaborative poetic / photographic project that began as part of an exhibition commemorating Canberra’s 2013 centenary.

The book is divided into three sections: ‘Where we live’, ‘Memory places’ and ‘Paddocks and perambulations’, with each Hetherington poem facing a ‘companion’ photograph by Webb. The collaborators describe how they used a call-and-answer process to create these parings: ‘Jen took photographs, which Paul then used as springboards into poems. Paul’s poems led, in turn, to Jen taking new photographs or editing existing ones.’ And while Hetherington is no stranger to ekphrasis, he explains in an interview with Verity La that ‘I did not wish my poems to be ekphrastic or descriptive works; I wanted them to be companion pieces; pieces that spoke to what Jen had seen and made; and which saw and were made differently, but in strongly connected ways.’

Introducing the book, Webb and Hetherington highlight their desire to step outside well-worn, tourist-friendly impressions of Canberra and ‘record ordinary parts of town, the places where people live and work and shop’. But while the result is nothing like a tourist guidebook, the commemorative origin of Watching the World means its depictions of the city are often admiring, at times even ode-like.

This celebratory quality, along with the book’s clearly delineated subject, puts Watching the World at a slight remove from Hetherington’s latest collection, Burnt Umber, and his 2013 work, Six Different Windows. They are broader in scope and often grapple with more intricate themes. By contrast, Watching the World is a moment of rest during which Hetherington has focused on succinct poems that condense around a single idea. ‘Summer’ shows this emphasis on straightforwardness and short, declarative lines:

Long grass burns with late autumn light as if so much waste of the passing year is suddenly consumed in softest fire

Hetherington tends towards iambic metre in many of his lines, but is careful to interrupt the pattern before it becomes overpowering. In ‘Balloon’ this steady tempo suggests the progress of Canberra’s early morning beacons:

Memories march like bayonets; your sense of yourself is a shred of words; and too much thought is never enough to take you where a shady green fell on your body like darkening joy –

It won’t surprise anyone familiar with Canberra to hear that the majority of these poems have a pastoral element. But before looking at Hetherington’s language more closely, it’s important to acknowledge the role of Webb’s photographs. Rather than offering a single answer to each poem, they act more as counterpoints, suggesting multiple interpretations of Hetherington’s lines. Human subjects are very few, with Canberra’s planned and unplanned landscapes the dominant theme.

Her work represents both instantly recognisable Canberran images – Telstra Tower, Parliament House and Anzac Parade’s memorials – and less obvious but just as representative subjects like a yellow lawn seen through a bus shelter window, walkers braving a sudden downpour, or dark clouds hovering above an uninhabited car park. In the companion poem to the latter image, ‘Airport’, Hetherington captures one of those moments when Canberra’s sky-scape dwarfs everything beneath it:

Horizons pull until all’s misshapen – a protean weighing of cloud-form and distance.

In his blurb for Watching the World, Peter Rose uses the word ‘Protean’ to describe contemporary Australian poetry. But if we are writing and reading Australian poetry in a period marked by change and difference, it’s also worth noting the consistency in Hetherington’s writing here. There could have been a temptation to use this collaboration as a reason to experiment with aspects of form, language or perspective. Instead, perhaps because these poems were first written for an audience that might not regularly encounter poetry, Hetherington has distilled each line, zeroing in on lucidity and approachability.

What’s particularly fascinating is the further consistency between Hetherington’s approach and that of a number of other writers in his poetic community. Profiling Hetherington after his 2014 residency in Rome (during which he finalised Burnt Umber), the Canberra Times describes Canberra as ‘a town fairly creaking with published poets’. With so many working writers in a population of just under 400,000, it’s hardly surprising to find resonances between the language of poets like Geoff Page, Alan Gould and John Foulcher, all of whom share Hetherington’s skill in ensuring clarity.

Of course, drawing boundaries like this to describe a ‘Canberra school’ is fraught. Any similarities we can find among Canberra’s more well-known poets leaves a community of unpublished and emerging writers out of the definition, not to mention those writing in nearby communities that don’t technically sit within the ACT. If there are legitimate through-lines to be found, these poets’ literary connections to one another are probably much less significant than the influence of Canberra’s singular, famously deliberate design.

Alan Gould is acknowledged for the idea behind ‘Waltz’, the poem that begins Watching the World. ‘Waltz’ addresses Canberra’s status as a place conceived on paper. It introduces the city’s ‘straight-drawn streets, / curves, crescents and rounding circles’ along with the houses that line them:

street by street they seem to waltz – stammering into blazing statements like an algebraic magic written on the pastured earth in irreducible expressions.

This question of the ‘pastured earth’ is one that many poets familiar with the Canberra region, most obviously Judith Wright, have spent years chronicling and questioning. But where a poet like Wright poses large, often troubling questions about anthropocentric impact on this environment, here Hetherington is writing from a more contented standpoint. In ‘Eucalypts’ we feel the warmth of ‘extravagant, broken sunshine’; in ‘Stepping’, rain takes on an almost sensual quality as it ‘flicks leaves / like agile fingers’; and ‘Bird’ shows us ‘ribbed and green-lit shade’.

That said, there are moments when Hetherington ‘dreams a past / into the paddocks’ textures’ (‘Notion’) and Canberra’s pre-colonial history comes into focus. This theme is strongest in the poem that matches Webb’s wide shot of Parliament House (‘The House’):

A building that stands for squatting and settling; erasure of stories; for naming again what had been named – excising land that snakes in courses of knowledge and lore

Canberrans go to great lengths to remind other Australians that although the city is the seat of Parliament, this doesn’t make politics central to their lives. As Les Murray has it in ‘The Canberra Remnant’, residents are occupied with other things, ‘safe from the Government of the Day’. Hetherington navigates this paradox by giving politics a peripheral seat, his poems more often returning to larger questions: Where are the fault lines between Canberra’s landscapes and its residents? When do these landscapes lose out? And where is Canberra’s Indigenous history in its comfortably urbanised present?

One Response to Alice Allan Reviews Watching the World: Impressions of Canberra