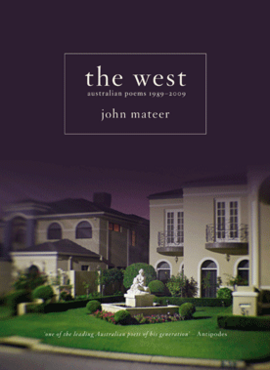

The West: Australian Poems 1989-2009 by John Mateer

The West: Australian Poems 1989-2009 by John Mateer

Fremantle Press, 2010

Since the publication of his startling first collection Burning Swans in 1989, John Mateer has established himself as one of the key Australian poets who, for the absence of a better term, can be broadly labelled post-Generation of ’68. What my clumsy terminology seeks to indicate is that Mateer (alongside other younger poets such as those appearing in the seminal 2000 anthology Calyx) follows in the general direction of earlier innovators while making crucial, although not necessarily generational, departures. The West, a substantial selection of Mateer’s Australian-published poetry of the last two decades (he has also published poetry in Portugal, Japan and his native South Africa, among other places), presents potent instances of his unique, unsettling poetics.

In his perceptive introduction to the book, Martin Harrison observes that the title, The West, hints at both Mateer’s home state of Western Australia as well as an awareness of the poet’s positioning in a broader, socio-cultural milieu that “definitely cannot mean Third World or developing or sub-economic or black.” This double meaning – which, according to Harrison, is “typical of Mateer” – I believe hints uncannily at a third, and in my opinion, central theme of Mateer’s poetry. If the term indicates both the physical setting of much of Mateer’s work as well as the inescapable ethno-cultural framework out of which he writes, then his poetry is ultimately also about the conflation of geography and ideology, that is, the nation. In my reading of The West, it is primarily the putative idea and identity of Australia that Mateer’s poems seek to signify, interrogate and challenge.

There’s no reason to either over- or understate the fact of Mateer’s non-Australian national origin, or to read too much or too little into the titles of the book’s individual sections, such as ‘Among the Australians’, ‘Exile’ or ‘Nothing But a Foreign Breeze …’. Mateer’s poems pursue and enact ruptures in common perceptions regarding Australia’s natural landscape, social mores and history. To use concepts developed by the contemporary philosopher Alain Badiou, by naming the voids in the situation of Australia, that is, by turning his attention to things that are conspicuously absent within given Australian settings, or by presenting what is apparent and obvious as mysterious or ambiguous, Mateer’s poems break with commonly held ideas about this country and instigate new, at times disturbing, perspectives.

In the book’s first and most personal section, ‘Exile’, Mateer seems to have collected snapshots of his earlier life à la confessional poetry alongside moments of intimacy and self-reflection. But, even at their most conventional, these poems turn the reader’s attention away from what is most visible and readily accessible toward what is hidden or irretrievably lost. ‘The Canadian Memory’, for example, begins as a rather routine autobiographical piece about a childhood memory (“Along St Lawrence River, through / dense thickets of hand-like twigs / in pockets of snow, we played games”) before evolving into a much more eerie, macabre recollection:

My great-uncle drove

trucks across the ice when the bridge

into Toronto was a log-jam of

cars tiptoeing on salt:You keep the door open just in case …

Some boy I never knew was torn away. Found

miles downstream by slow Mounties

in rubber boots.

It’s not only the story of a child’s death in a frozen river that gives this poem its unnerving quality. That the speaker “never knew” the drowned boy negates the sort of pathos and sentimentality associated with such a tragic scenario, and the reader is instead encouraged to wonder what really took place. Why did the great-uncle’s ominous words end in ellipsis rather than a full-stop? Is there something being elided or excluded from this recollection?

Unanswerable questions, enigmatic references to absent beings, allusions to unknowable facts and a profound uncertainty about the poet’s environment and its inhabitants characterise Mateer’s poems and provide them with their dark, engaging intensity. After exposing himself and his personal life as deceptive, illusory events in the book’s first section – in terse, short poems such as ‘On History’ and ‘(Mirror)’ in particular – Mateer sets out to undermine and destabilise what I earlier referred to as the situation of Australia. In the poem ‘The Surfer’ from the book’s second section, ‘Among the Australians’, for example, the portrait of a supposedly agile and healthy Aussie surfer is disrupted by the insinuation of the surfer’s deep distrust and fear of the body’s fragility, resulting in a fetishistic obsession manifested in “countless posters of / blue and perfectly riderless waves” in lieu of any actual surfing.

In the book’s third section, ‘The Nature’, Mateer writes against the tradition of Australian landscape poetry. His subversion of natural sites and Australian flora and fauna, as with his dismantling of his self and personal history in the book’s first section, is achieved through a subtle yet steadfast articulation of voids and absences, such as the “dim luminous incarnation” of the extinct marsupial thylacine in ‘Visitors Centre’, or the ghostly “invisible river” running “over broken rock geometry, as extinction” in ‘Towards Wilpena Pound’. In ‘The Scar-Tree of Wanneroo’ an “old but still living tree” in the Western Australian town may appear real and present, but its “scars where bark was prised off / for coolamon or shield or piece of shelter” trace “an historic silence, an empty hurt,” pointing at the absence of the Aboriginal peoples’ history and heritage in much of contemporary Australia.

Poems about Indigenous Australians and Aboriginal history comprise the book’s fourth section, ‘Mokare’s Ear’, and, as this title indicates, it is the literal and figurative remains and echoes of the past that are the foci of these haunting poems. Perhaps more so than most other non-Indigenous Australian poets, Mateer has shown a determination to explore, at times controversially, a very subjective relationship with the country’s original owners. The 19th century Noongar warrior Yagan is of particular interest to Mateer, but it is not the warrior’s biography or his ongoing cultural significance for Western Australian Aborigines that frame the discourse of sequences such as ‘Talking with Yagan’s Head’ and the lyrical ‘In the Presence: Fifteen Songs’. Mateer’s poetry instead invokes the silence of the warrior’s spectre and emphasises the intangible yet visceral power of the image of his severed head:

Yagan,

Like the sooty turning-fork prongs of trees after a bushfire,

you, to whom these words are sung, are a silence.

Addressed through this muted song,

you are more intimate than prayer, closer than my own flesh.

Considering that the central tenet of the public discourse apropos of the exhumation, repatriation, possession and burial of Yagan’s head has been the view of the warrior’s skull qua a literal skull, Mateer’s personal, almost spiritual, rapport with the object as the signifier of a permanently vanished event is rather contentious. What right does a non-Indigenous Australian (and a migrant one at that) have to claim “intimacy” with a murdered Aboriginal figurehead? Why is Mateer shirking from taking sides in the so-called history wars? Is he for or against the black-armband version of Australian history?

Questions like these are left provocatively unanswered, and the reader of The West is instead encouraged to wait, alongside the speaker of the poem ‘The Cockatoo’ in the book’s fifth and second last section, for “the sulphur-crested cockatoo unsteadily perched on the back of a chair […] to hold forth on the subject of AUSTRALIA.” According to Mateer, the country may be seen in its emblematic fauna, but all that can be heard from such an image is an unintelligible repetition of its own name. It is up to the reader, addressed directly in the poem ‘Invisible Cities – for Domenico de Clario’, to turn “the unimaginable continent” with its “deserted industrial city” into “a dreamscape” where:

every leaf sparkling in the avenue of stilled elms

will become a question from another, invisible world.And being here will be like sitting at an electric piano,

hearing the murmuring of your fingers

like transferring all your possessions to some other room,

then taking the floor as your bed,or like painting a nocturne blindfolded, the cityscape being in that darkness

Based on this selection of Mateer’s poetry, it would be apt to say that he too covers Australia, its people, ecology and history in a shroud of darkness and transforms the country’s images, myths and emblems into the traces of “another, invisible world”. His project is not at all an example of poetic obscurantism, but an invitation to the reader to see Australia as something other than what’s been described as “this far-flung province of the Empire of the Obvious” in one of this remarkable and engrossing book’s final poems. His poetry is a gripping incitement to reconsider and revise the themes of nationhood, history and identity.

If, as literary scholar Livio Dobrez has written in A Companion to Twentieth Century Poetry, the postmodernists of the Generation of ’68 ceased writing about the nation and national self-consciousness, then it can be said that poets such as John Mateer have revived these themes to radically problematise and contest them. As such, I can cautiously label Mateer as a post-postmodernist, and I can also unreservedly describe The West as one of the year’s major poetry publications.