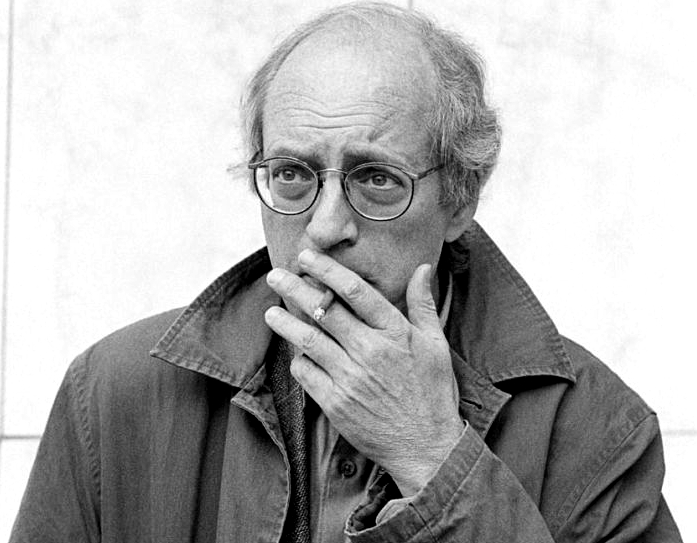

Image courtesy of ABC

While the prevailing formula for the contemporary essay seems to be information plus thesis – a collection of facts held together by authorial intentions – Eliot Weinberger’s approach is striking for a deceptively simple difference. Rather than drawing conclusions for the reader, he lets information become its own argument, however oblique. The resulting essays are open-ended, riddling things, many of which gain meaning in aggregate, like those in Wildlife – whose contents correspond between the animal world and ours – and An Elemental Thing – which come together to create a ‘serial essay’.

This approach extends to Weinberger’s political articles, the most well-known of which is ‘What I Heard about Iraq’, a kind of documentary prose poem that reconstitutes public statements and backroom whisperings to become a damning indictment of the invasion.

Weinberger is also a renowned translator – of Octavio Paz, of Jorge Luis Borges, of Bei Dao – and a regular contributor to the London Review of Books. In October, New Directions will publish The Ghosts of Birds, which promises to pick up where An Elemental Thing left off.

Aden Rolfe: I think the first essay of yours I read was ‘The Dream of India’, a collage of imagery and descriptions of India, taken from texts written in the five hundred years prior to 1492. It made me sit up and think about what an essay is and what it can be. As someone who Forrest Gander describes as ‘having cracked open the essay form’, what are your thoughts on the potential of the essay?

Eliot Weinberger: Like any art form, the essay is potentially limitless within its constraints, which is why I’ve never understood why it generally has remained stuck in the first-person narrative (a.k.a. the ‘personal essay’), as though all paintings had to be self-portraits.

AR: Essays like ‘Paper Tigers’ and ‘Wrens’ pull together information from diverse texts, cultures and folklores. What starts you down the trail of these works? At what point do you think ‘I’m going to write an essay about tigers’?

EW: In the first case it started with a question: When Blake wrote ‘Tyger, tyger’, had he ever seen a real tiger? That led to exhibits of exotic animals in London at the time; the contemporary obsession with Tipu Sultan, the ‘Tiger of Mysore’; and on to various myths and beliefs about tigers. One thing leads to another, if you let it.

In the second case, a poem by a 3rd century Chinese poet, Chang Hua, got me following the wrens: how this tiny anonymous creature is known in many languages as the ‘King of Birds’. The annual ritual sacrifice by the Wren Boys. And, bizarrely, the exact correlation of the presence or absence of Wren Boys, two contrasting types of Neolithic tomb structures, and the current borders of Ireland and Northern Ireland. No need to make this stuff up.

AR: What does the research process look like for these essays?

EW: I’m intimidated by libraries and never go. So I use the books I have around and, since the internet arrived, academic articles and public domain texts. As I’m not writing scholarly articles, I don’t feel the need to have read everything on the subject. You could say I improvise with the materials I have in hand. Or, more accurately, you could say I’m lazy.

AR: In the title essay of Karmic Traces, you write: ‘In classical China, every act of writing began as an act of reading.’ I’m keen to know about the relationship between critical reading and your own practice.

EW: Robert Duncan used to call himself a derivative writer, which was inaccurate in his case but probably accurate in mine. Most of my writing comes from my reading, modified by what I’ve seen of the world. I’m just retelling some old stories – but that’s half of what literature has always done.

AR: John D’Agata has said that your approach is to document information rather than interpret it. You gather facts together and make limited intervention, or at least seem to. How much shaping of the material does take place, as opposed to just getting out of the way?

EW: Well, first of all, my essays are not collages of found – or as they now say, ‘appropriated’ – texts. I gather the information, but I write and rewrite the sentences that contain that information. Obviously I decide what to include or omit, and how to organise it. I suppose it appears to be a ‘limited intervention’ because I’m not explicitly drawing larger conclusions. Perhaps I’m deluded, but I consider this information to be like the daffodils in a poem about daffodils.

AR: In ‘Abu al-Anbas’ Donkey’, the eponymous donkey refrains from translating the word ‘shanqarani’, withholding meaning from both its owner and from the reader. This reminds me of Walter Benjamin’s conception of the art of storytelling: keeping a tale free from explanation, letting a reader draw their own conclusions. Why leave a work open in this way?

EW: Theology and ideology are supposed to answer questions and art is supposed to ask them. The former theoretically have one reading and the latter an infinitude of readings. But in fact the interpretation of theological or ideological texts is always changing, always in dispute. People are killed over it, unlike art. So what, then, would be a ‘closed’ work, a work with only one meaning? An instruction manual? These, of course, are notoriously difficult to read and may be the only genuine examples of ‘lost in translation’. An advertising slogan? They contain their own mysteries, such as (sorry to date myself): ‘Coke is the real thing.’

AR: How does your work as a translator more broadly influence the material, the passages, the paraphrases, that make their way into your essays?

EW: My essays are not about me, they tend to come from other cultures, and they do not speak in a single obstinate voice. In that sense, they’re like the work of a translator.

AR: One thing I love about your work is that you present information without qualification. When you write about the shared language of the people and birds of Mt Bosavi in Papua New Guinea (in ‘Where the Kaluli Live’), there’s no ‘apparently’, no ‘they believe’, no ‘so it is said’. What kind of responsibilities come with taking an authorial position like this?

Pingback: OLMIŃSKA: Niekończąca się gra motywów. Recenzja esejów Eliota Weinberger