Photo by Jane Zemiro

Pam Brown is not only one of Australia’s most prolific and important poets writing today, but also one of our richest archives on the history of late twentieth century Australian poetry. Since this is Cordite’s Sydney issue, I thought an interview with her might evince a valuably multifarious image of, perhaps, Australia’s most speedily shifting poetic landscape.

In particular, as a contemporary Australian poetic history of the late twentieth century stems in part from poets closely associated with the city, it only made sense to ask Pam Brown, Sydney avant-garde collaborator, instigator, publisher and poet. Author of 16 books and 10 chapbooks, Brown has lived most of her life in Sydney, and now lives with her partner in the suburb of Alexandria. As well as offer new understandings of a period thoroughly historicised, I hoped Brown’s personal recollections of the formative 1970s would illuminate the significance of those small press and handmade initiatives of the past that Astrid Lorange sees as ‘non-causal’ and ‘monadic’ in her Jacket2 archival commentary. Naturally, I was not disappointed.

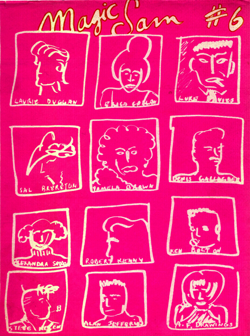

Corey Wakeling: It would be contentious to few to cite Sydney as central to a poetic boom in the 1970s. It was a movement of experimentation and poet-led production of magazines, pamphlets and books, in which you took part with a number of once Sydney-based associates and friends. These are some of Australia’s most important poets: Ken Bolton, Laurie Duggan, Sal Brereton, John Tranter, Rae Desmond Jones, joanne burns, Philip Hammial, Kris Hemensley, John Forbes, Stephen Kelen, and others. Magic Sam, the magazine of poetry you helped put together between 1975 and 1982, with editors Anna Couani, Ken Bolton and Sal Brereton, collects many of these people in its pages. Tell us about how you came to be involved with these poets.

Pam Brown: At the outset I should say that, as everyone knows, the slant given to past events depends on whoever reports them. My bias and experience of anything I can remember from the 1970s and into the 80s is bound to be different from others’ – and bound to be tempered by my own various and tentative examinings of those years during the decades since then. Nothing is fixed when it comes to the past.

Starting in 1972 I had published three small books of poetry, and also graphics, in an ‘underground’ way (what’s now called ‘independent’ publishing). I had also read poems in public in Sydney at the annual Balmain reading, the Paris Theatre and a few other places. I was engaged in a variety of counter-cultural activities – sculpture at Martin Sharp’s Yellow House, UBU films’ lounge-room screenings at our house and, earlier, film-making (Albie Thoms’ Sunshine City) in our flat on Crown Street, Surry Hills. Plus, after Pat Woolley moved the offset printing press out of the front room of our Surry Hills house across to Glebe Point Road around 1972, I set up Cocabola’s Silkscreen Printing at the front of the ‘shop’ and the offset printery became Tomato Press.

We made political pamphlets and an anti-censorship publication called X – with photos of friends having sex of all kinds – and distributed it widely. I was writing record reviews for Rolling Stone magazine and The Digger newspaper and I had a couple of day jobs in a bookshop and at a retro clothing stall at Paddy’s Markets. By 1975/76 I worked as a mail sorter and was playing music in the women’s band, Clitoris Band, and by 1977 I was involved in the anarcho-feminist theatre group, the Lean Sisters. I was also making video and film by then. I made a film with Gill Leahy about two female outlaws, Cattle Annie, in ’77. So I suppose that’s a brief background. I kept on writing poetry alongside these pursuits.

Ken Bolton told me later that he’d been writing to me for poems for a year or so at the various addresses listed on my books. But I had always moved. In 1977 they tracked me down and Anna Couani called by the sharehouse where I was then living in Glebe. She told me that she and Ken (whom I’d not met) were editing a magazine called Magic Sam and they’d like to publish some of my poems. It sounded interesting. It was a thick gestetner and screenprint magazine with some terrific illustrations, and included interviews with and the work of contemporary artists as well as poets. It was nice to be invited and I gave them some work. Anna and Ken also had a poetry book imprint called Sea Cruise Books.Some of the poets you’ve mentioned – John Tranter, Steve Kelen, Philip Hammial – were elsewhere for me at the time. (I met Steve in the early ’80s. I didn’t get to know John until around 1988). I had heard about Poetry Magazine and its difficult transformation to New Poetry from Laurie Duggan, who I’d been friends with since 1970 or ’71. But those magazines and their quarrels didn’t really register as being very innovative, edgy or interesting to me. They were the magazines of an institution called The Poetry Society of Australia. They seemed quite conventional and I thought that they were very dull-looking productions. Adelaide poet-artists Rob Tillett and Richard Tipping’s earlier MOK magazine (1968/69) had looked much more exciting to me. I was reading poetry from the US. The bookshop where I worked had City Lights’ books and other American publications. I had heard Andrei Voznesensky, Allen Ginsberg and Lawrence Ferlinghetti read in Sydney in 1972.

CW: I get the sense from Kris Hemensley’s introduction to Applestealers, published in 1974 and edited by Colin Talbot and Robert Kenny, that between the years 1968 and 1974 there was a perceived difference between the underground, small press poetry of Melbourne and the alternative canon proposed by John Tranter and Robert Adamson in their initiatives like New Poetry. However, for publishing poetry in Australia, the ‘70s seemed especially lively, with new magazines like Magic Sam often publishing poets from around Australia and perceived factions side-by-side. And then, as you’ve already noted, a variety of incipient poetry journals from around Australia were in limited, national circulation.

PB: I moved to Sydney in 1968. That year Tom Shapcott and Rodney Hall’s anthology New Impulses in Australian Poetry was published. It attempted to gather poets taking different directions from preceding traditions. I hadn’t published much then and I read it with great interest. It may not have been the editors’ intention but that anthology included poets who can now be seen as a ‘new’ establishment: Les Murray, Bruce Dawe, Geoffrey Lehmann, Chris Wallace-Crabbe, Andrew Taylor, and so on.

I had nothing to do with the editorial activities of John Tranter and Bob Adamson at the time. They are both five years older than me; it might not seem much, but when change moved rapidly through the late ’60s–early ’70s, five years did mean difference. I had only heard of Bob Adamson in gossip about his skirmish with John Forbes at the Balmain poetry reading. My poetry and most of the poets in the earlier Shapcott/Hall collection weren’t included in John Tranter’s 1979 anthology The New Australian Poetry. In fact, Tranter’s anthology didn’t register with me until years later when I began to notice (and doubt) the eponymous phrase ‘generation of ‘68’’. But now that Tranter’s and Adamson’s products have been thoroughly historicised and though John Tranter’s selection was aiming at a fresh perspective at the time, I’m not sure that what they presented of Australian poetry was an ‘alternative’ canon. Perhaps their drive was mainly ‘generational’ and not necessarily a challenge to an existing status quo – as if they wanted in on a pantheon rather than to deconstruct one. New Poetry didn’t seem ‘new’ to me in the mid-1970s.