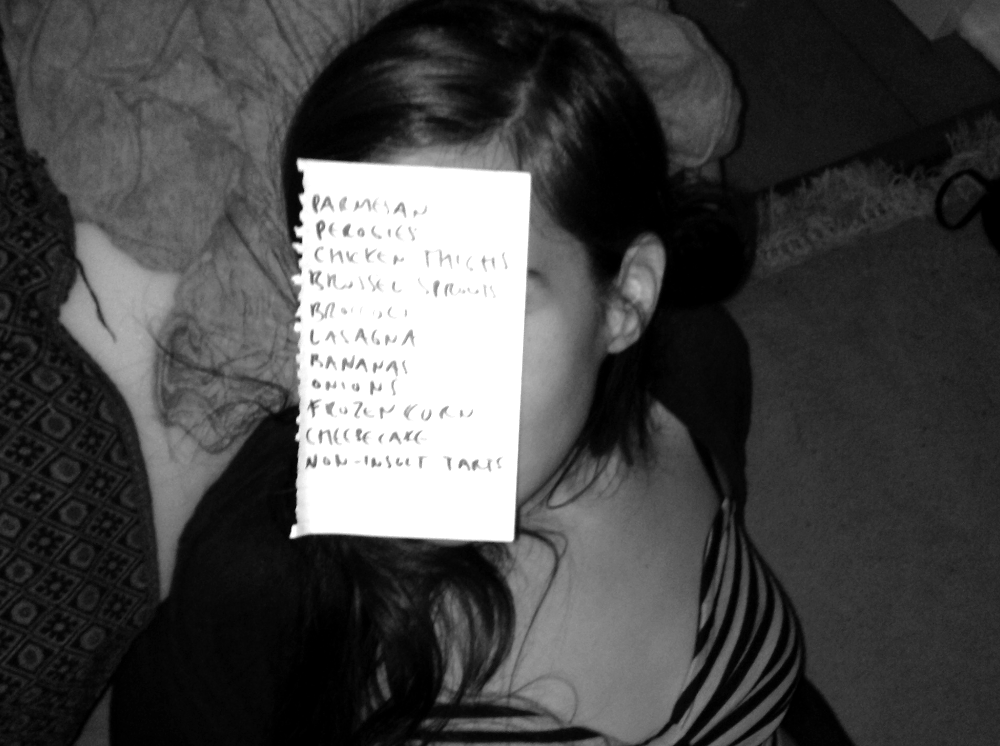

Image courtesy of Cristine Brache

Cristine Brache is a Latin American poet and artist newly based in Toronto. Her work explores the nuanced power dynamics inherent in many of our relationships. Brache’s practice incorporates video, sculpture, poetry and a multitude of limited edition objects, prints, t-shirts and publications. She and I met online in 2013, when she was living in Guangzhou, China, and making videos and taking photographs of unexpected and emotional English-language phrases on t-shirts. I was working in a temporary office for writers in Docklands, Narrm (Melbourne), writing a novel set in a twisted version of the area in which I was writing. There was a connection both emotional and about the notions of the pages we were inhabiting – whether offline or on – Brache and I chatted online, sharing poems and artworks, and she would send me images, links and stories from the places she was travelling to.

We met physically in London in 2014, where Brache was working towards an MFA at Slade School of Fine Art and I was in residence at Arcadia Missa working towards publication of the aforementioned book, Danklands, and an exhibition to accompany it. In Brache’s apartment we shared time, tea, mixed gummies and stories, deconstructing our perceptions of the strange city we’d unexpectedly come to share. We continue to correspond and below is a conversation regarding poetry, power and practice.

Holly Childs: Your work uses, and subtly repurposes, stories and tropes traditionally given or marketed to people who experience misogyny as tools for engaging with men or the male gaze. I’m thinking of your sculptural work of the past 18 months, in which viewers encounter traces of a dozen games, spinning dice and cards on tables and in cages, word games across languages, playground rhymes, often alongside abstracted self-portraiture, a ‘who is she’ self as subject, as muse and mirage. I like your work ‘Jailer’s Keys’ – six keys constructed from mother of pearl, one engraved with the message ‘NOTHING BUT VIOLENCE’.

Cristine Brache: Making is a game of communication and language for me. I find there is a lot of room to play with various modes of speaking: associations, words, symbols, context, histories, self-portraiture, etc. Each mode is rife with its own respective bank of meaning. For example: I am the mirage. With each body of work my intention is to create a personal syncretised subset that can be readily decoded if the viewer is able to connect and allow their own meaning to answer to the holes between the objects or words in question.

With ‘Jailer’s Keys,’ there’s a gender role reversal. Mother of pearl is often considered yonic due to its delicate appearance and texture, as are escutcheons, since their keyholes function to be penetrated. I wanted this feminine material to occupy something phallic, a key. They’re phallic beyond their physical appearance and function, as they allow passage to restricted areas. Their presence is authoritative, defining boundaries and distinctions between public and private space. The etched words on the key come from a poem I wrote:

FEMALE TROUBLE them blues that nothing-but-violence just nature just moon

HC: I am also curious about your work ‘Self portrait without bed’. The objects on each bedside table appear to be expressions of games and riddles of absent figures sleeping on two sides of an absent bed: a set of playing cards with queen of hearts revealed on one table; two keys alongside a glass of water and a clock with no hands on the other. From these sparse elements I get a feeling of the unique and nuanced relationships of people who share a bed, as well as the games we play, the intimacies we reveal, and the positions we come to occupy when we share personal space.

CB: ‘Jailer’s Keys’ led me to begin thinking of my body as both a public place and home. I am not sure if my body belongs to me still. So much is read and taken from it based on its appearance. Elements of the home are deeply personal, maybe the bed is the most personal place that a person can physically occupy. Bedside tables say so much to me. The last and first things you need before and after sleep are located on them. Things you keep nearby when nights are sleepless. I tend to have cycles of insomnia and when I do the clock preys on me. Clocks keep counting minutes even if it feels as if time has stopped moving:

FALLEN HANDS a clock with no hands keyhole mouth carefully inlaid with no one will notice

Cards can be used for divination but also invite chance and risk. On my side of the nightstand in ‘Self-portrait without bed’ I wanted to give myself hope on a sleepless night, when inside it feels as if I have no bed, nothing to hold me. I placed ‘western playing cards’ made of porcelain and replaced the suicide king’s (king of hearts) face with my own on the top half of the tile. On the bottom half of the ‘card’ or porcelain tile, I did the same thing but with the queen of hearts, who holds a flower; the suicide king holds a dagger or sword to his head. The idea for this came from the title of the exhibition these porcelain tiles first made their appearance in: ‘I love me, I love me not.’ The opposing images on the ‘card’ is a pendulum that swings between self-love and self-hate.