“The little magazine is not difficult to define,” write David Miller and Richard Price:

it is an anthology of work by strangers; an anthology of work by friends; an exhibition catalogue without the existence of the exhibition; a series of manifestos; a series of anti-manifestos…It’s printed by photo-litho; or typed onto a mimeograph stencil…It’s a twenty-year sequence; or it turns out to be a one-off. 1

It is inclusive of a spectrum of literary productivity, bearing simultaneously the weight and gait of outsider and coterie, commercialism and unprofitability, both harbinger and hindsight. One clue to its elusiveness, or effusiveness, is the notion of its distance from a perceived literary norm.

This last element [i.e. “distance from a notional norm”] elides identity politics with poetics; it is in poetics that the “classic” element of the little magazine is encountered. A classic little magazine, in the view of the present authors, publishes the work of a group of artists or writers who assert themselves as a group (e.g. the Surrealist Group of England’s publication of The International Surrealist Bulletin in the mid Thirties) 2

What then could be said to be our contemporary little magazines and small presses? Especially considering the collecting of such small press publications at the institutional level of the poetry archive, or repository. These are some of the issues that arise within “the dynamics of literary publishing” as it stands today. 3

I. Ontology for Little Magazines and Small Presses

Tom Montag points to the eclipsing of studies of small presses by those academic interests vested in little magazines. The relation between small presses, little magazines, and the academy may be further complicated by, invested in, or fraught with the mission and ethos of the modern and contemporary poetry archive. [Q. The author confesses to working as Mary Barnard Research Assistant to The Poetry Collection of The University Libraries, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York. ] And this may particularly relate to how literary items are stored in an archive: serials, like little magazines, clustered by title; monographs, or small press titles, sorted by individual author in the service of bibliography.

Montag, writing in 1978, gives some reasons for the above eclipsing:

A little magazine can be indexed; its editorial vision can be analyzed; its sphere of concern over a period of years can be assessed. By contrast, the nature, concerns, and editorial vision of the good small publisher may often be difficult to ascertain because, first, the small press editor does not have the convenience of “editorial notes” in which to set down his literary tenets; second, the publisher may present diverse kinds of writing, dissimilar in all respects except for that intangible quality, something not easily described 4; and, third, students of literature generally seem more interested in the development of particular writers (and hence the bibliographies of particular writers) than in the larger dynamics of literature (to which the bibliographies or “lists” of publishers are relevant). 5

It is true (to some degree): the manifesto has been a central focus of study regarding Modernism; also, mission statements, prefaces, and introductions. 6 Into the seams of the small press go the small publishers’ poetics, as allegedly translucent as that of the editor or designer, positions for which the small publisher may often stand in. 7, 8

Other concerns also reveal, as through magnitude (or, circulation) and production timetables: the little magazine is often abler to present a broader (if not immediately deeper) swathe of poets as well as divergent or sympathetic aesthetics; and, the magazine may typically appear with greater frequency. We might also ask how these would-be rivalries play out in the more current scene of digital production, both online and in print: the little magazine may now post and update in an instant, proffering more and longer features. 9 Similarly, print-on-demand publishing and e-books have allowed small press catalogs to grow—in some cases—exponentially. 10

Montag later makes apparent the simultaneity of much small publishing—that is, the overlap between little magazines and small presses, more often than not the same laborer educing these categories of the bibliography. 11 It may be hazarded that while the labor remains uniformly that of the “small publisher,” and the volume of small publishers proliferated via digital technologies more affordable in terms of access, the scope of little magazine-versus-small press may be a limit we are culturally reaching with a speed outstripping even that of digital propagation and its labeling.

Labor and affordability also become variables—leaving practitioners of the now to “ambiguate” the new division of small press and little magazine labor. That is, amid this occlusion, it may be helpful to differentiate how small publishing, its vehicles and venues, relate to or resist the commercial production and consumption of what is literary.

II. Ultra-Heterogeneity and the Subtraction of a Critical Readership

In April of 1965, a Modern Language Association of America conference was organized by poet and critic Reed Whittemore to address the theme of “The Little Magazine and Contemporary Literature.” Various speakers came to represent their varied platforms, including those of the little magazines Partisan Review and Prairie Schooner, kayak and Kulchur; including William Phillips and Karl Shapiro, George Hitchcock and Lita Hornick; also, Allen Tate, Wayne Booth, and Peter Caws. Far more intriguing than the presiding egos of what William Phillips dubiously dubs The Literary Situation12—a term later called into question by said presiding egos of that literary moment—was Phillips’s caution against the interests and influences of funding regarding the small publishing endeavor.

We all know about the evils of money and the virtues of the affluent society, though we sometimes forget that these are contradictory ideas. And we are familiar with the long cultural tradition exposing the corruption of industrial society. What I want to comment on here is simply the way the power of money recently has tended to break down old literary traditions and standards and to stunt the growth of the more or less homogenous and educated audience that is necessary—or at least used to be thought necessary—to the continuity of literature. 13

Despite his (literally) demoralizing angle, Phillips draws out the notion of reception, one we talk about often enough in the digital- and activist-minded paradigms of discourse as a “critical mass” in readership, or audience. To emphasize, while Phillips’s analysis may sound to us partly reactionary, it is also partly cautionary of an age we have perhaps come to inhabit, where he warns:

The three main trends of our time, or at least the three that have excited most of the critical arguments, might be said to be academicism, commercialism, and extremism. (I almost added a fourth: awardism, the endless pursuit of awards, prizes, and grants and the constant hopping from one writers’ conference to another…)14

On the absorption of writers—specifically poets, who are most often the small publishers of poetry magazines and presses—into the academy we have had some speculation (see note 25), and the same with the awarding of prizes that has lent itself to suspicion. 15 Less so of—to use a jingoistic term here—the hybridity found in the new publishing models, in which author and publisher16 align common interests in bringing forth magazines, chapbooks, and monographs, rather than the conventional ideal of the wealthy publisher courting and patronizing the talented author of the garret. 17 But I am getting away from Phillips: he explains that he isn’t fearful of the nonhomogeneity of audience so much as the dissolution of an educated and informed “critical mass” (in my phrasing) of readers before a “glossy” capitalistic magazine culture; and, I would hazard, commercial publishing houses. Corporate capitalism’s nonstop drive to elongate the desirability of a product, or to replicate it for the longevity of its sales-appeal, leads to what Phillips sees as the watering-down of literary output for popular consumption, and a demand-sided market for the author; furthermore, he believes it leads to at least two kinds of authors: “the rich and the regular.” The homogeneity of a readership (or masses), therefore, is not the same as the homogeneity of a critical readership: not where the market knows no literary value, only capital. And where literary production serves—above the ideals of a readership, or even an aesthetic—only mass consumption.

One might wonder what kinds of modern reading communities this will have engendered by our own moment.

III. Get Your Small Press Chaps Here!

Little magazines were ambivalent at best about advertising. From Mark Morrison’s assessment of modernist British examples, while

the Egoist, and its predecessors the Freewoman and New Freewoman, might seem to exemplify the type of coterie publication that turned its back on mass audiences and published either for posterity or for what Ezra Pound would call the “party of intelligence” 18

he likewise argues

that the writers and editors of the Freewoman/New Freewoman/Egoist were attracted to the proliferating types of publicity of an energetic advertising industry, and that they also attempted to adopt mass advertising tactics—not always directly from the commercial enterprises of the mass market magazines, but rather from the suffrage and anarchist movements…19

Thus we might read literary promulgation and capitalist consumption as a twofold sign of literary modernity. Seeing these literary fractures derive smaller, niche markets—or consumptive coteries—within a larger publishing realm of production and consumption also furthers Phillips’s concerns (and perhaps Montag’s) regarding not only a dilution of the discursive but also of the reign of its dissemination.

To some of these midcentury small press editors and publishers the threats of falsely competitive awards contests and commercial advertising, and “extremism,” rivaled that of academicism. 20 How may these concerns have changed given the abovementioned streamlining of poets’ vocations with academic posts?

It is noted at the time of the 1965 conference that the Partisan Review had recently been absorbed into Rutgers21; likewise, Prairie Schooner had been invited as a representative academy-funded magazine. Paralleling the withdrawal of literary community from commercial publishing, and the simultaneous entrance of many poet-publishers into academia, one finds the attribution of academic funding for small publications. Thus the endowments associated with departmental chairs and academic institutions have come to subsume large portions of the expenses of wider reaching and well turned out magazines, such as the Partisan Review. (Thinking today of the University of Chicago’s affiliation with the Chicago Review , or discretionary chair endowments bestowed upon graduate student productions, such as at The University at Buffalo where the David Gray Chair, among others, has historically (and, one might say, nobly) supported such small presses and affiliate magazines as Cuneiform, P-Queue, Atticus/Finch, and Pilot. ) These affiliations may also extend the reach of coterie now vested by the academy, even while it may simultaneously delimit poetics.

Literary magazines are what Karl Shapiro called “the penultimate form of publication for literary works”: “A work printed in the literary magazine has only two destinations: the book or oblivion.” 22 From this stance, Shapiro hazarded that the magazine—opposed to the monograph—was expendable, the book, unexpendable. Consider the general consensus that fewer monographs are being purchased by libraries or printed by publishers, and that therefore perhaps fewer are written or even read. The chapbook and little magazine might thus be thought to correct Shapiro’s assessment: the other side of oblivion may be a proliferation of little magazine publications and small-circulation chapbooks. 23

And then attention that has been given to the movement of avant-gardists into academic (and tenured) positions. 24 But are these institutions, made proper by Shapiro as “institutionalism,” those of the academy? A time of wan funding in the United States—particularly at state-funded colleges and university systems in California, New York, and Wisconsin—as well as rising tuition fees and student debt in the U.S. and in Western Europe, say otherwise. Institutionalism, as Shapiro indicates, has little to do with the academy other than its abandonment, leading us to question the generationality of a rift between poetry and the academy proper. 25

This is where we leave off Shapiro, and much of the partisan wrangling at this MLA conference. But not before we bear in mind Shapiro’s prescient analysis of The Literary Situation (that term loathed by Phillips’s fellow panelists) as it antecedes our own: “What we have of the avant-garde today is a direct reaction against the growing institutionalism of the arts and the society it defends” 26—prescience here in that Shapiro was speaking directly from his experience as editor of Prairie Schooner and those little literary magazines associated with academic institutions.

Consider now the interests of the collection at an institutional level, such as that found in the University at Buffalo’s Poetry Collection. James Maynard, speaking of the Collection’s founder Charles Abbott (in an earlier interview with the author), tells how “Abbot realized that to capture fully the trajectory of any poet’s work he would need also to collect little magazines, anthologies, broadsides, and in some cases English translations.” 27 It was Abbott’s foresight to recognize that little magazines were worthy of collecting, as well as small press literary output, alongside mainstream monographs. To collect, as is stated in the Poetry Collection’s collection policy, “without prejudice.” Such was Abbott’s coy reasoning of not paying writers for donations of their “wastebasket” manuscripts, drafts, and ephemera. For,

he felt there could be no sure way to ascertain the relative value of any given poet’s papers vis-à-vis another’s…In general, manuscripts simply didn’t have the same perceived value—literary or monetary—as they do today. [28 .Ibid. Abbott asked particular poets—such as Pound, Williams, and Moore—to send him, as donations, those drafts that would otherwise be committed to their wastebaskets.]

Maynard goes on to speculate how

In today’s academic and economic markets, I think many writers have a markedly different attitude toward their body of accrued work, viewing it now as a form of investment. 28

And these changes must decidedly reflect the marginal economic fortitude of many small publishing endeavors—especially as they might also reflect the economically marginal statuses of their publishers. Poets do now what has elsewhere been called the “shadow work” of free consumer labor under capitalism. Thus the evidence of poetic labor is completely subsumed by a market value.

While the rarity of archival materials and the “auction block” prices attributed to them may indicate a greater collecting practice on behalf of institutions, two notable features may belie this appearance. First, this presumes a magnitudinous poetry institution, replete with endowments resilient against recent economic flux; such is decidedly not the case, of late, in higher education, and certainly not for the literary arts, or for The State University of New York library system. Second: this stance requisites a knowable small press universe.

One might hazard that the small press literary community of the 1920s was, while diverse and far-flung, far smaller than today, thus allowing for greater networking and connectivity between the curator and what Maynard calls “ambassadors” to the collection, or those figures who have historically advised the curators, and thus extended their purview of the small press publishing:

I think the collection from the beginning has always relied on various kinds of ambassadors—for instance, there are letters from Nancy Cunard advising Abbott on what African-American poets to collect. 29

Across a contemporary map of small press publishing—or, the Literary Situation we now find ourselves in—academic institutions may still be viewed as oppositional, where the pedigree of commercial publishing has so frayed reception, and when ultra-heterogeneous communities exist without interstice, Buffalo’s repository, so often considered “the collection of record” for modern poetry, may, going forward, appear to waver as cost, commercialism, and reaction to commercialism increase at once the literary object and the its resistance to collectability.

IV. A Reading Room

As Lita Hornick of Kulchur makes evident at the 1965 conference,

this is a revolt not so much against the academy as against literary mandarinism. These writers say that they do want to reach and influence a wider audience, and I think that’s healthy. I think it even more dangerous for poets to write for the editors or the readers of the quarterlies than to submit to the pressures of the academy or the marketplace. I feel that the little magazine does not have to publish literature that’s by definition incomprehensible to the public and therefore unacceptable to the machinery of commercial publishing. 30

I think Hornick is pulling at quite a tangle here, at sympathy with our own Literary Situation, as stated above: the incommensurate poetics of the small press: of aesthetics, form, format, distribution, officiousness, avant-gardism, and coterie—to name a few.

It is the archive that may have a few things to teach us about such tangles.

I walk among the glass encasements of the Poetry Collection’s in-house exhibit, James Joyce & His Literary Circles: Paris, Personalities, Presses. Here is one of the letters referred to above by Jim Maynard, from Nancy Cunard to Charles Abbott: she sends a poem she has translated “on Spain written by a Yougo-Slave [sic] volunteer who fought there for several months,” signed by the poet; she talks of England’s (and France’s) stance toward Spain, and a lack of action on either’s part toward military aggression; laments the inadequacy of the League of Nations to assess—let alone redress—events in Spain, and wonders at its future demise; forewarning: “The students of the future will have a time rich in horror to study.” 31 Still, the small publisher has time (amid this and two other letters on display) to advise Abbott on how to get in touch with poets Kay Boyle, Cedric Dover, Nicolás Guillén, and Langston Hughes, as well as where to find her groundbreaking international anthology Negro while Abbott is in London. 32, and Aug 29, 1937, all three sent from 43 Boulevard des Capucines, Paris.] It was the monumental project of commissioning, compiling, and publishing Negro that came to subsume the early small press efforts found in Cunard’s The Hours Press; and it was her same press that in 1930 alone issued Samuel Beckett’s Whoroscope, Robert Graves’ Ten Poems More, Laura Riding’s Twenty Poems Less and Four Unposted Letters to Catherine, as well as Pound’s A Draft of XXX Cantos! It may have been through Cunard’s ambassadorship to the Poetry Collection that Abbott was able to acquire these and many more monographs from The Hours, or how he became alert to the many literary publishing circles in which Cunard participated. If the poet or researcher of today were to try to collect the handful of 1930 titles listed above it would cost, at rough estimate, more than 10,000 U.S. dollars. 33 Furthermore, the collection offers a great deal more to the poet and researcher, given the correspondence between curator and small publisher, as it gestures not only to Cunard’s social and professional network and milieu but also—more importantly, given our discussion—to her publishing poetics.

As Cunard recounts in her memoir of these years, These Were The Hours, she purchased her “old Belgian Mathieu press” from William Bird of Three Mountains, which has its own auspicious beginnings and record:

Though Bird financed it himself and regarded the Three Mountains as a hobby, its first six books published in 1923 were indeed artistic achievements. All in the same agreeable tall and narrow format, the six were: Indiscretions by Ezra Pound; Women and Men by Ford Madox Ford, who incidentally ran his Translatlantic Review from an office upstairs…Elimus by B.C. Windeler; The Great American Novel by William Carlos Williams; England by B. M. Gould Adams; in our time by Ernest Hemingway. 34

In one such “wastebasket”-letter from the office of William Carlos Williams we find this account of the labors of the letterpress directly from Bill Bird:

We had a rotten time getting started—first the difficulty of finding an English comp[oser], next the foundry fell down on the delivery of certain sorts,—but we are well under way and Pound’s book will be off the press the end of next week if no new embêtement supervenes. Then we tackle Hueffer [Ford], which will take a month—say the end of February. Elimus is short—three weeks at most should suffice. Yours is relatively long, but should be printed by the end of April […] Glad to hear of your projected trip this way. By that time the 3 mts. press will either be broke or blooming. 35

Thus the longstanding relationship between self-financed and small press ventures… (Three Mountains was also the first publisher of Gertrude Stein’s The Making of Americans, in 1925.) It is in the reading room at an archive of record that such importantly tangential sympathies as type and letter are revealed, allowing for an ever and even more material account than the memoir can provide.

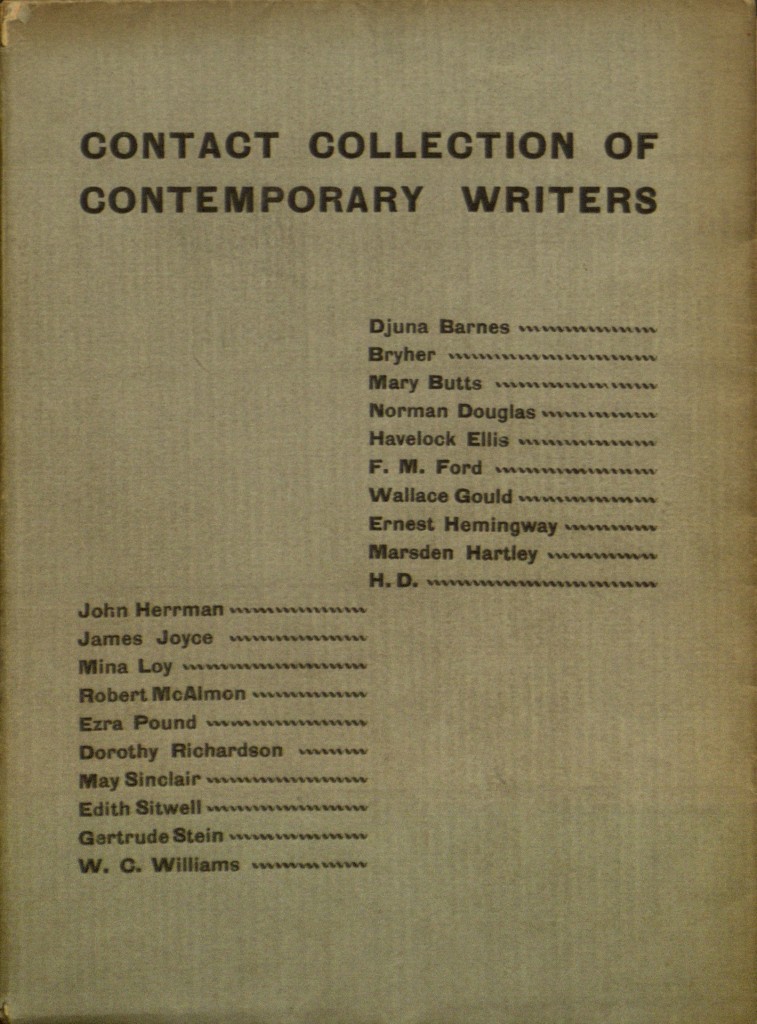

Along with Ford’s Transatlantic Review, Three Mountains also shared an address with Robert McAlmon’s Contact Editions36 whose 1925 Contact Collection of Contemporary Writers reads like a Who’s Who of high literary expatriot Modernism (e.g. Fig. 1).

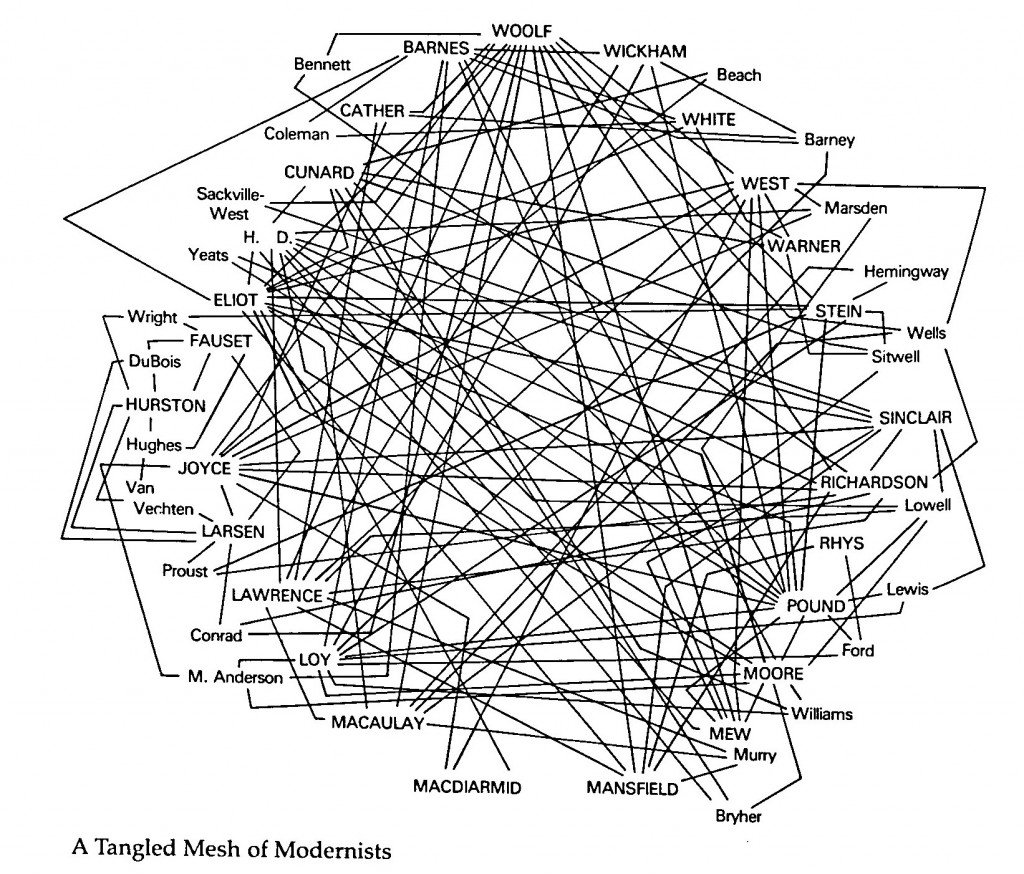

It is also such a recorded archive that allowed pre-digital diagramming like that found in Scott and Broe’s The Gender of Modernism (Fig.2).

The Gender of Modernism: A Critical Anthology. Edited by Bonnie Kime Scott and Mary Lynn Broe. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990: 10.

Archival collections also make possible compendia like the one by Miller and Price, who write of their effort:

This book is not only an annotated bibliography but a union catalogue of holdings as well. For each entry, we have consulted the catalogues of the British Library, Cambridge University Library, the National Library of Scotland, Trinity College Dublin and University College London’s Little Magazines and Small Press Collection.

The Poetry Library [Southbank Centre], although not so strong in its holdings for the first half of the century, is an extremely rich resource for later magazines: in many cases, equal to or better than the national and academic libraries. Its holding are placed beneath the list of libraries with a century-long breadth. 37

There are therefore different collections of differing strengths in terms of scope and foci, and the geographic location and access policies of these institutions mitigate what might be revealed to us of the poetics of small publishing—as exhibited through small press monographs and little magazines.

But to return to Hornick’s assertion, for whom are our small presses today publishing?

V. Archiving the Icons of the Now

In assessing the progression of monograph and little magazine into the overlapping discourse of the small press chapbook series, an alignment of cultural production with academia is notable. Also, the distancing of (viably profitable) commercial interests from academic funding and publishing, or, in Hornick’s words, “the pressures of the academy or the marketplace.” 38 Maybe in tracing a literary situation in terms of the poetry scene a repository now faces, a case might also be made for the interests of the contemporary poetry archive.

I give you, by way of illustration, some examples of the now I consider fine. 39

Exhibit A: Muthafucka

Muthafucka was, per editorial admissions, “an irregular, locationless journal of the arts.” 40 The publisher’s imprint appears only on the second (and last) issue, with no date on either; in order to communicate with editor Mitch Taylor, beyond email, one could write care of various folks at changeable addresses. This magazine maintained a low overhead, with photocopied, standard 8½- by 11-inch papers, stapled along the left margin, and with laminated cover. This magazine also followed a typical trajectory: slimmer first issue, with less-well-known and predominantly male contributors. Then, nearly doubling its page count to include far more recognizable contributors and gender parity; plus, in the second issue, the small press or avant-garde “titans” it looked to in establishing its poetics.

The second issue, sadly, was the final Muthafucka, a lamentable loss of an adept “survey” of some burgeoning scene. Such is often the case with little magazines (as noted by Miller and Price). Luckily, the presence of an ambassador to the collection among the contents of the first issue ensured the Poetry Collection’s early identification and procurement of this publication. While easily reproduced, each issue was printed in a run of only 100, each numbered. Thus, part of Muthafucka’s intent was to lasso a limited audience, intentionally falling short of a wider purview for the sake of establishing a quickening of contact.

Exhibit B: Western New York Book Arts Collaborative

Some publications are intentionally limited, as in the case of artist’s books.

Such is the case with 8 Poems by Richard Tuttle:

Published 2011 by the University

at Buffalo Art Galleries, State

University of New York.

Generous support for 8 Poems is

provided by Steve and Kate Foley/200

Printed and bound at Mohawk

Press, Buffalo by Richard Kegler

and Chris Fritton in an edition

of 200 copies using Caslon types.

Cover paper is Handmade Saint

Armand. Page paper is Revere

Suede. Cast paper boards from

blocks cut by Richard Tuttle. 41

This piece falls within the archive’s mission threefold, being at once a book of poems, commissioned by the University at Buffalo, and printed locally. The book came about through a visit visual artist Richard Tuttle paid to the Western New York Book Arts Collaborative, during which he and printers Kegler and Fritton discussed the possibility of working together on a book. Some weeks later, a letter arrived from Tuttle suggesting that WNYBAC use a manuscript of his recent poems for such collaboration. 42

These are the kind of endeavors that make small press work possible: the coalition of University with private support, the interaction between established artist and startup press. In keeping with the “smallness” and limited engagement of such endeavors (not to mention the high profile of the artist), these runs are usually priced high in an effort not only to raise the visibility of these fine press publishers, but also to raise funds for the continuation of their lesser-known—and just as vital—efforts. Given that the item is local and affiliated with the University, the archive was able to procure copies. But what of such efforts from other cities, and through other universities and private securities—How find these out or afford them? The academy and its affiliates may have, in instances such as these, become aligned with the small press—and not a commercialized establishment.

The rise of small press printing as resistance to the market—and, to some extent, the market’s latent appropriation of the digital—has led to an increase of fine-press endeavors, intended to both rarify the printed item as unique unto that printing establishment, and to fetishize the printed item in order to garner funding toward the ends of sustainability and futurity. There is no doubt that fine press printers deserve and should command wages commensurate with the quality of their craft; but a discrepancy opens between the money earned by the printer and that earned by the poet. In most cases, the run of printed material is shared with the poet—even the profit. But in many less well-known cases of small press publishing, however, publication is the poet’s reward. And this opens further questions regarding inner- and interdisciplinarity and institutional funding. Unlike the Muthafucka example above, the fine arts press—or art book publisher—has revenue to gain. With Muthafucka, contributors could safely presume the editor was undoubtedly not turning a profit, and therefore the editor’s work could be said to be a form of service. The archive enters then as would-be patron, subscribing to the little magazine in order that the editor not go broke (per William Bird) fulfilling the act of literary production.

Small presses make for small budgets, whereas fine arts command a much shinier dime. Given the allocation of funds for small press journals, chapbooks, and zines, it is often impossible for the archive to purchase those items made within the networks of fine arts printing—at least, not where they must compete with the budget of the fine arts museum. With an increase of limited broadsides and portfolios (many of these reprinting works previously published in monographs or chaps) as well as an increase in poet-visual artist collaborations, the archive must inevitably fail to collect many of these materials.

Exhibit C: Song Cave

The archive first became aware of the Song Cave endeavor when a University at Buffalo graduate had a chapbook issued from the press. By that time, some of these limited chapbooks had filtered into the curators’ mailboxes as gifts, but upon making contact with Song Cave’s publishers, the archive discovered that other of its titles were already out of print.

The project of the Song Cave is an admirable one, wherein editors Ben Estes and Alan Felsenthal issue handsomely uniform pamphlets by a wide range of authors, thereby proliferating and sustaining the field of the now. The print run for these pamphlets, or chapbooks, however, is quite limited: 100 per chap, each usually signed. One hundred copies is less than many people’s holiday card list, and certainly less than the average person’s Facebook distribution. Who then are the recipients? Other poets featured in the series, perhaps, or within other finite networks.

Luckily, the publishers had the foresight to reserve a number of copies of each title (making the 100-count distribution notably smaller) and were quite amenable to making these available to the archive; furthermore, a subscription could be established for future reservations and purchasing of the series. Without that initial contact via one author, however, this well-profiled and broadly ranging series would have failed to pass into the record of this archive. This is a sizeable quandary, whether dealing with an author as-yet unheard of, or blip in the bibliography of Fanny Howe.

Exhibit D: Dusie Kollectiv

Further questions arise for the archive given the Song Cave example: How will these series be represented in the archive and through its digital interface, or online catalog? As mentioned above, per an arrangement directive regarding monographs and little magazines, monographs are catalogued and stored by author, and little magazines grouped together by title, then chronology within title. The chapbook series, or collaborative network, proffers new challenges as to how to see the series, virtually. While series names or presses can be made searchable, just as a press name like The Hours is, the increasing prolificity of chapbooks from little magazines and small presses questions the archives traditional sorting by format. 43

A collective like the Dusie Kollectiv further problematizes such questions.

Dusie is an international community in which participants print one hundred copies of original work for distribution to the other (presumably one hundred) members of the collective. Fascinating in its expansion on the notion of coterie, and for the variety of its printed materials, such reception is decidedly finite. And while this collective maintains a virtual presence with much of the content downloadable, it challenges the archive’s intention to physical examples of first and substantive editions.

If not for the prescience of certain members of the Kollectiv, the archive would never come to record and house such excellent examples of the now as Megan Kaminski’s Collection, sewn with black thread in blue papers.

grape soda Dear mother dear May dear exile to Texas

metal trough knives wedge into wallpaper blue violets peel

ice window from wood siding cold beans and calf brains

blur skank no talk just leaves rustling in heat under the

drop soft canopy soundless that time in the woods

scrape rock that time in the barn reappear to rake ashes

scrape asphalt swallow daylight drag songs out for one last

scarlet flowers round raconteur protract rounder colder

44.]

Exhibit E: little red leaves

Somewhere between the limited fine arts edition and the small press magazine chapbook series falls a project like that from little red leaves textiles. Sewn in remnant cloth, issued in runs of sometimes only 50, each is a pocket-sized joy of small press endeavoring.

How, though, can this conversation be heard if the archive is not already in touch with one of the publishers or authors? The idea that all such networks are knowable forecloses the (quite accurate) possibility that many such networks exist independent of the archive and its ambassadors. Unless we were to presume, dubiously, that social networking sites have now made all poets (and their aesthetic oppositions) “friends” of the collection. But perhaps not all endeavors are meant to be knowable; this too is a resistance to commercial interest and institutionalism, as well a resistance to the inevitably knowable digital age. (And yet, the insidious commercial gamut of such social networking…)

In such an ignorant state, the future student of poetry would have to hope for the best of willed intentions on the parts of dead poets, who might bequeath their small press libraries to such an archive. Else, said future student will not discover how Jamie Townsend’s Matryoshka was sewn in floral remnants of autumnal hew, and how the publishers’ design wove blind stitch of flora-lineation through and among free-floating stanzas, revealing poetics of line and material sympathetically hewn.

Exhibit F: Mixed Blood

Loosely affiliated with Penn State via its on-faculty editors, this sparsely turned out periodical, in slim red covers, was rich in variety and content, asking for contributions of poetry, poetics, and critical writing that carried on the conversation of “the contemporary African American avant-garde.” 45

Consciously, and telling of its poetics, the editors of Mixed Blood added very little by way of frame to writings contributed; thus the stencil of the pared-away independent press in the hands of the tenured-practitioner. 46 And though this example is slightly earlier than others mentioned, it is notable for its range of writers and topically themed agenda. Issues were in fact the publication of papers from a plenary series held at Penn State, and the first number carried talks by Amiri Baraka and Juliana Spahr, as well as poems by both and by Jen Hofer, Erica Hunt, and Ed Roberson, with the second number featuring a younger set, including such nascent members of the now as Evie Shockley.

At the writing of this survey a third installment has never been issued.

Exhibit G: No, Dear

It is not only the digital whose fleetingness can escape the watchful ambassadors: so the many little magazines that last one, maybe two issues (like both Muthafucka and Mixed Blood); and those which last but whose early issues are long since disseminated.

No, Dear is such a journal. Published out of Brooklyn by a quadrangle of editors, it features many contributors unknown to me (a good sign for the archive worker!), as well as few now considered highly collectable by any small press poetry standard: Kyle Schlesinger, Lisa Jarnot, Julian Brolaski.

The archive caught on to No, Dear by issue three—and by then the prior two issues had disappeared into the scene of readership; such early examples are requisite in assessing how a little magazine, or small press agenda in general, develop. With only 150 copies printed per issue, the archive is happily now on the mailing list.

VI. A Postscript and Postal Script

To return to norms, what evidence gathers? For one: that the institution, as far as representing an edifice of “official verse culture,” can no longer be said to be symmetrical with the academy. Also, how current trends in funding—or lack thereof—among private, philanthropic, and academic institutions have not only aided the transition to digital technologies, but also perhaps assisted the production and circulation of small press publications. Also, that the return of the chapbook seems somehow both a furthering of small press enervation and a retreat from its modern mainstreaming.

The archive of the Poetry Collection in Buffalo occupies an interesting space, being both a library of record for modern and contemporary poetry, and under protectorate of the state-funded institution—it is a branch of this system. And, as far as the metaphor of the well-nourished branch reaches, some may even see it, or the principles by which it orders and empirically organizes the literary, as one with the literary establishment (or empiricism at large) they wish to challenge via the poem or the concept of the book.

Little magazines and small presses still operate in, among, and across the peripheries of literary culture; that seems—per definition—part of their purpose: to anthologize the now perpetually and to any given end. That said: the study of such seems to remain on the periphery of literary materiality, even if not in terms of scholarship, even as studies of little magazines have become vogue. But this may still point to Tom Montag’s point that scholarship has favored the little magazine or the small press, even where the two may still be seen to overlap. Let me explain. Of late, far more attention has been given to the concept of group theory, presented in terms of the “group biography” or the emphasis, within cultural studies, on interdisciplinarity. 47 One thinks of a continuum of studies, beginning perhaps with Hugh Ford’s Four Lives in Paris (North Point, 1987) and including John Carswell’s Lives and Letters (New Directions, 1978), Susan Cheever’s American Bloomsbury (Simon and Schuster, 2006), and numerous studies turned out each year on Woolf and the Bloomsbury of London. These are often in the service of biography, or even bibliography on the level of the individual. But what of small press culture itself, its evidence and its poetics?

Countering or cantilevering Derrida’s now-canonical Archive Fever (University of Chicago, 1988) is the ultimately unknowable small press and digital worlds—cartography in need of tooling let alone dissemination of its maps. Small press activity therefore passes between the straits of willful obsolescence and such a dubious prospective as what I will call “writing for the archive.” The role of the repository, after all, is to record the conversation, rather than to commission or persuade it. (Or maybe we have come to a new life for the archive, beyond the philanthropic…) The making of the map of poetry is endless and exhaustive, and our desire to know it at all makes the pursuit deeper and more horizonless with each discovery. And is this is as it should be; and is this not but what we wanted—from a small press perspective: a less canonical universe of critical reception? 48 As Peter Riley has it:

I’m interested in there being as many [poets] as possible. It doesn’t mean you tolerate dullness, it just means you seek quality (and you do seek quality) without limiting its chances. In poetry as in any other realm you seek good beyond predicated categories. 49

This map is still being written; and if the archive has not your mark, your chapbook or little magazine, let it find its way here—

Poetry Collection

420 Capen Hall

Buffalo, New York

14260-1674

Works Cited

Anderson, Elliott, and Mary Kinzie. The Little Magazine in America: A Modern Documentary History. Triquarterly/The Puschcart Press, 1978.

Contact Collection of Contemporary Writers. Paris: Contact Editions, Three Mountains Press, 1925.

Cunard, Nancy. These Were The Hours: Memories of My Hours Press, Reanville and Paris: 1928-1931. Edited with a foreword by Hugh Ford. Southern Illinois University Press: 1969.

Howe, Fanny. The Lamb. Northampton, MA: Song Cave, 2011.

Kaminski, Megan. Collection. Zürich: Dusie, 2011.

The Little Magazine and Contemporary Literature: A Symposium Held at The Library of Congress, 2 and 3 April 1965. Reed Whittemore, organizer. Modern Language Association of America: 1966.

Maynard, James. Interview with Edric Mesmer, February-March 2011. Yellow Field 2. The Buffalo Ochre Papers: Spring 2011.

Mixed Blood, Nos. 1-2. Giscombe, C. S., William J. Harris, Jeffrey T. Nealon, Aldon Lynn Nielsen. The Pennsylvania State University, 2004-2007.

Miller, David and Richard Price, comps. British Poetry Magazines 1914-2000: A History and Bibliography of “Little Magazines.” The British Library and Oak Knoll Press: 2006.

Morrison, Mark S. The Public Face of Modernism: Little Magazines, Audiences, and Reception, 1905-1920. University of Wisconsin Press, 2001.

Muthafucka. Taylor, Mitch, ed. Luminous Flux, c. 2009-2010.

No, Dear. Brandt, Emily, Alex Cuff, Katoe Moeller, and Jane Van Slembrouck, eds. Brooklyn, 2009-2011.

Riley, Peter; Tuma, Keith. “An Interview with Peter Riley.” The Poetry of Peter Riley. Nate Dorward, ed. Toronto: The Gig 4/5, November 1999/March 2000.

Scott, Bonnie Kime, and Mary Lynn Broe, eds. The Gender of Modernism: A Critical Anthology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990.

Townsend, Jamie. Matryoshka. little red leaves, 2011.

Tuttle, Richard. 8 Poems. Buffalo, NY: Mohawk Press, 2011.

- David Miller and Richard Price, compilers. British Poetry Magazines 1914-2000: A History and Bibliography of “Little Magazines.” The British Library and Oak Knoll Press, 2006: ix. ↩

- Ibid., x. ↩

- Tom Montag’s phrasing, in “The Little Magazine Small Press Connection: Some Conjectures,” with emphasis in original. Elliott Anderson and Mary Kinzie, eds.. The Little Magazine in America: A Modern Documentary History. Triquarterly/The Puschcart Press, 1978: 576. ↩

- What Miller and Price have called a poetics. ↩

- Ibid. It should be noted that “concern” is a touchstone word for Montag, and Concern/s the title of his 1977 collection of essays and reviews (Milwaukee: Pentagram Press; cited in Anderson, et al.). ↩

- Andre Breton’s Manifestos of Surrealism (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1969), Tristan Tzara’s Seven Dada Manifestos and Lampisteries (London: Calder, 1977), Mary Ann Caws’ Manifesto: A Century of Isms (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001), Drew Milne’s “Agoraphobia, and the embarrassment of manifestos: notes towards a community of risk” (Parataxis feature, Jacket, Dec. 2002; http://jacketmagazine.com/20/pt-dm-agora.html). ↩

- I use the word “translucent” to invest the near-transparency of such editorial, design, and publishing assignations; it is and should be accepted that these features of any literary production are not incidental. ↩

- And let us not, as Montag reminds, overlay small press publishing with a seamlessly fitted poetics of bookmaking, typography, or book arts alone, as some or none of these variables may apply. ↩

- Here I am thinking of Jacket, John Tranter’s digitally and digital groundbreaking magazine. ↩

- And here I am thinking of the dynamic, print-on-demand—now also e-book—publisher BlazeVOX, published by Geoffrey Gatza. BlazeVOX also maintains a biannual online magazine by the same name, formerly subtitled “an online journal of voice.” ↩

- In Montag’s wording: “That the editor of a little magazine is frequently also the editor of a small press should not surprise us” (577). ↩

- By “dubiously” I mean to mark the problematic nature, or “risk” in Milne’s conjecture, of naming one’s contemporary moment as such, even while the term serves usefully in identifying the changes Phillips had wanted to demarcate against a backdrop of earlier little magazine publishing. ↩

- William Phillips. “The Literary Situation” in The Little Magazine and Contemporary Literature: A Symposium Held at The Library of Congress, 2 and 3 April 1965. Modern Language Association of America, 1966: 11. ↩

- Ibid, 10. Phillips digresses upon the elusive careerism of the conference-going writer or teacher-academician. ↩

- One is reminded of such suspicion surrounding Jorie Graham’s selection of her future partner’s work for the University of Georgia’s prize, as well as other awards given to former students, made public by Foetry.com in 2009. ↩

- Note here the disappearing of the editor, whose labor is foisted upon both author and publisher. ↩

- Here I am reminded of the awe (some would say naivety) demonstrated by some authors’ reactions to BlazeVOX publisher Geoffrey Gatza’s hybrid model of sharing costs, documented in the poetry blogosphere. (Contrast this with David Rakoff’s spoof on the publishing naïf found in his collection Fraud, wherein a publishing assistant is downtrodden that his boss gives him a gift for Secretary’s Day; the remedy found in this satirical essay is a martini luncheon with a coworker at the Algonquin.) ↩

- Mark S. Morrison. The Public Face of Modernism: Little Magazines, Audiences, and Reception, 1905-1920. University of Wisconsin Press, 2001: 85. Morrison also interestingly alludes to an informal sharing of editorial labor among the writers associated with the Egoist. ↩

- Ibid. This connection between suffrage, anarchism and the arts is well documented in such works as Janet Lyons’ “Militant Discourse, Strange Bedfellows: Suffragettes and Vorticists Before the War” (Differences, Vol. 4, 1992). ↩

- Phillips: “I am using the term ‘extremism’ purely descriptively; and it goes without saying that, no matter how foolish or bad some avant-garde writing may be, the bad things seem to be prerequisite of the good ones” (12-13). ↩

- Discussion following the Friday Morning Session, The Little Magazine and Contemporary Literature: A Symposium Held at The Library of Congress, 2 and 3 April 1965. In the afternoon session following is Allen Tate’s talk “Subsidized Publication,” focusing on some “quite large” little magazines with academic affiliation and support. ↩

- Of note is Shapiro’s slippage between “literary” and “little.” ↩

- I would include in here also the manifestations of such in the digital. ↩

- See Manuel Brito: Means Matter: Market Fructification of Innovative American Poetry in the late 20th Century. New York: Peter Lang, 2010: 74 n.1. ↩

- “It is strange,” Shapiro writes, “how little we have progressed since, say, the 1920’s. The writer in the twenties knew how little to expect from the commercial press, the university press, the foundation, or the government. He therefore established magazines which would be free of those institutions. Undoubtedly the richness of that time of writing owes much to this assertion of independence” (19). See the amusing accounts of courting funding in Margaret Andersons’ memoirs of the Little Review, My Thirty Years’ War (New York: Covici, Friede, 1930); also, her correspondence with Ezra Pound regarding subscription and (free) distribution in Pound/The Little Review: The Letters of Ezra Pound to Margaret Anderson (New York: New Directions Pub. Corp., 1988). ↩

- Karl Shapiro. “The Campus Literary Organ” in The Little Magazine and Contemporary Literature: A Symposium Held at The Library of Congress, 2 and 3 April 1965. Modern Language Association of America, 1966: 19. ↩

- James Maynard in interview with Edric Mesmer, February-March 2011. Yellow Field 2. The Buffalo Ochre Papers, Spring 2011: 46. ↩

- Ibid, 47. On the generosity of many small publishers and poets, Maynard continues: “I would be remiss if I didn’t note how much the Poetry Collection continues to benefit from the generosity of donated materials, be they books, magazines, and even manuscripts. ↩

- Ibid, 48. ↩

- Discussion following the Friday Morning Session, The Little Magazine and Contemporary Literature: A Symposium Held at The Library of Congress, 2 and 3 April 1965. Modern Language Association of America, 1966: 29. ↩

- Nancy Cunard to Charles Abbot. Letter dated Sept 29, 1937. The Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York. ↩

- The other two letters I cite here are dated March 17, [1938 ↩

- I am using here, in early 2012, the competitively priced international web site of “small” booksellers, AbeBooks.com. ↩

- Nancy Cunard. These Were The Hours: Memories of My Hours Press, Reanville and Paris: 1928-1931. Edited with a foreword by Hugh Ford. Southern Illinois University Press, 1969: 4. ↩

- Letter from William Bird to William Carlos Williams, dated 8 Jan 1922; Paris. ↩

- Cunard: 4. ↩

- Miller and Price: xvi-xvii. ↩

- See Hornick, above. ↩

- Let it be noted that I restrict my examples here, as per my scope, to the call for an inquiry into the state of small press publishing and the archive as found in the U.S. today. ↩

- Muthafucka 2, from the colophon. Luminous Flux, 2010. ↩

- Richard Tuttle. 8 Poems. Buffalo, NY: Mohawk Press, 2011. I am using copy 9 of 200. ↩

- Thanks to Chris Fritton of the Western New York Book Arts Collaborative for sharing this background with me. ↩

- Serie d’Ecriture is a great early example of this problem in arrangement: issued from Burning Deck Press out of Providence, the series is “housed” in the archive as would be a periodical or serial, even though doing so leaves “gaps” in the bibliographic record of each featured author as found physically upon the archive’s shelves. ↩

- Megan Kaminski. Collection. Zürich: Dusie, 2011: [13 ↩

- Editors’ note. Mixed Blood, No. 1. C. S. Giscombe, William J. Harris, and Jeffrey T. Nealon. The Pennsylvania State University, 2004: 3. ↩

- This is made formal in coeditor Aldon Lynn Nielsen’s brief introduction to the second issue. ↩

- I am indebted to James Maynard for this insight. ↩

- This from a casual conversation with Michael Basinski, Curator of the Poetry Collection, January 2012: Isn’t the proliferation of small press publishing the democratizing answer to a handful of seminal giants? ↩

- Peter Riley, in interview with Keith Tuma. The Poetry of Peter Riley. Edited by Nate Dorward. The Gig 4/5, 1999/2000: 17. ↩