Statistics from the National LGBTI Health Alliance Australia acknowledge that when discussing the mental health of LGBTQIA+ people ‘it is vital to consider how intersections with other identities and experiences may impact on an individual’s wellbeing’ (2016). This includes people with disabilities, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, people of colour, as well as many other identities. While the right-leaning media may sensationalise trans and gender diverse folks, stating that we are only affluent attention-seeking millennials, the statistics show otherwise. Trans people are everywhere, throughout histories, cultures and intersections of life. We are working in your offices, buying groceries at your shopping centres, and peeing with escalating fear in public bathrooms.

In the final two stanzas of Part 1 there is a shift. Until this point the fictional app has been portrayed as a way to escape transphobic social interaction. In the final stanzas of Part 1 the reader is shown how this does not change the underlying reality, however, and how trans and gender diverse folk are still subject to public violence. The reader is confronted in the second person with harsh verbal abuse and slurs ‘hurled at you / on the street.’ In the app, this can be replaced with ‘a golden / retriever, barking joyously.’ The scene questions whether having an app that masks antisocial behavior is really a solution to the problem. How about educating transphobes not to yell at people from cars? Could transphobes instead see the difference in a person, acknowledge that difference, and roll up the window instead of rolling it down?

The accompanying piece of art shows us a person sitting on a public bench, perhaps waiting for a bus, with Trans Shield active on her phone. The reach of the app spreads a purple shield and changes the sign ‘clothes for women and men’ to the more inclusive ‘clothes for people.’ The single strands of the purple-pink thread meeting in a V-shape echoes the inverted pink triangle, the Nazi designation for homosexual men that later became a symbol for the early Gay Liberation movement. The piece also focuses on the man standing close by on the street corner, changing his slur to a compliment. As with the representation of buying groceries, here everyday aspects of life are gendered in ways which reinforce exclusions, both individually and systematically. The app layers a more inclusive experience over reality, but that does not change the underlying discrimination.

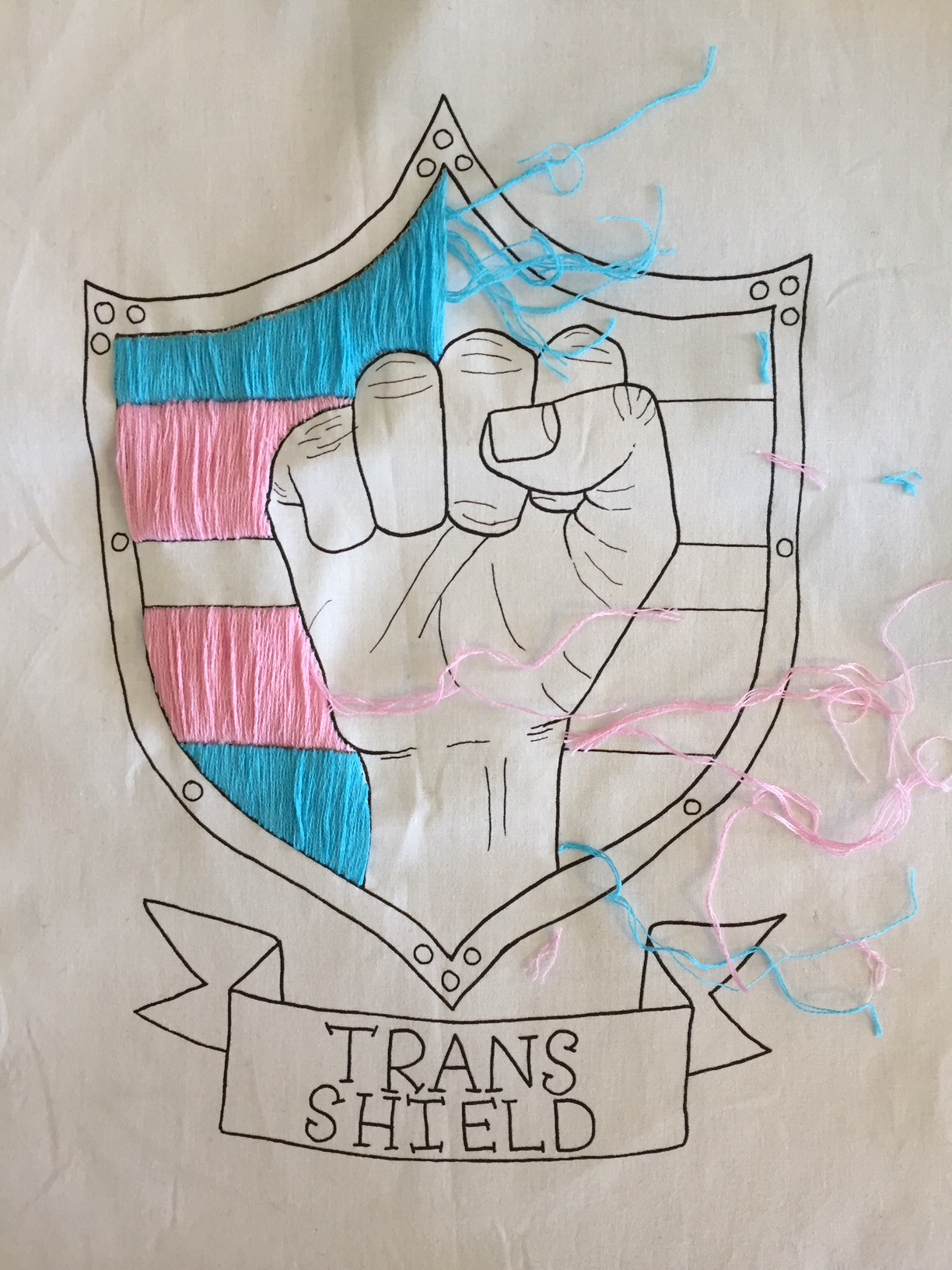

My choice to keep the original words ‘what a fucking freaky man’ and embroider over them with ‘what a lovely woman’ was a conscience decision, one rooted in craftivisim. This form of activism centres on practices of craft within feminism and other activist movements like anti-capitalism. Craftivism, a term coined in 2003 by writer Betsy Greer, uses needlework and other practices traditionally labeled ‘domestic arts’ and repurposes them for empowerment, action and expression. In this piece, embroidery rewrites a slur by piercing a needle through the fabric of transphobia: an act of resistance against the opinion that we are ‘freaky.’ Further, it participates in community actions to resist mainstream depictions that are exclusionary, derogatory and discriminatory. The embroidered words demonstrate trans and gender diverse people’s agency in creating realities that are safer and more inclusive, while at the same time acknowledging that mainstream discourses and spaces frequently remain unsafe.

Part 2 of the poem discusses the use of multiple profiles and the easy ability to edit details depending on a person’s gender fluidity or desire to explore identity. There is a dominant narrative within trans culture that is often used to make our trans-ness more palatable to cisgender people: that we ‘always knew’ we were trans. We mine our childhood memories, panning for those moments we can pinpoint and declare ‘see, it’s okay, I was always like this!’ While this can be a positive and life-affirming concept for trans and gender diverse people, this is not always the case, and it can make those without early-life justifications feel isolated from wider trans communities. We shouldn’t be required to rationalise ourselves and our identities to people, nor should we be forced to look at our transness as ever-fixed – because ‘who says / we can’t explore / who we are!’ This added component of Trans Shield would give gender diverse people the freedom they are often denied through discrimination and the societal pressure to ‘choose’ – the freedom to play, to explore, to have fun with gender while testing out new ways and ideas of being; to find forms of self-nourishment in both app culture and craft culture in ways that embrace play.

Part 2 also reminds the reader that they are reading the description of an app, this time offering ‘additional features’ such as Sleep Mode. This mode turns off the app so the user can ‘address the issue head-on,’ recognising that gender diverse people are often the ones correcting others on their gender, name and pronouns, being the ones burdened with the role of educator (and so often experiencing negative transphobic backlash in response). Statistics from the National LGBTI Health Alliance Australia report that transgender, non-binary and gender diverse people are at high risk of suicide, self-harm, depression and anxiety, especially young people. These health outcomes are directly related to experiences of stigma, prejudice, discrimination and abuse. Offering the fictionalised ability to choose those moments they take up the mantle of educators, this depiction of the app’s feature gestures to the exhausting, compulsory educative labour which trans and gender diverse folks are so often forced to perform.

Part 3 addresses these health risks head-on, referring to the ‘violence against / transgender and gender diverse / people, / especially / the violence against / and murder of / transgender women of colour.’ The developers of Trans Shield apologise for not being able to deal with these issues ‘within the current scope / of this app’ – these ‘broader / systemic issues’ are societal wounds that cannot be fixed with a simple tech-savvy Band-Aid. While an AR app like this could assist with the health and wellbeing of trans people and shield us from the microaggressions of daily life, it cannot compensate for the systemic transphobia we face, the violence against our trans siblings and ourselves. This passage also acknowledges the limits of tech culture as a method of dealing with discrimination. It can create spaces for more possibilities, but it is always embedded within society and culture. Further, it points to the burdens being placed on trans and gender diverse folk to be ever vigilant in creating a safer world for themselves, rather than turning the responsibility back onto wider society to stop perpetuating violence towards these communities.