These recordings contain no input from Beckett. Beckett’s presence has however appeared on an LP, though not his voice. In 1966 Claddagh Records in Ireland produced MacGowran Speaking Beckett (CCT3), a recording of selected soliloquys performed by Beckett’s close friend and one of his favourite actors, Jack MacGowran. Beckett’s reticent presence in the studio is heard in his gentle intoning of a gong that signifies the end of discrete tracks. (His brother Edward and his cousin John play the flute and the harmonium respectively.)

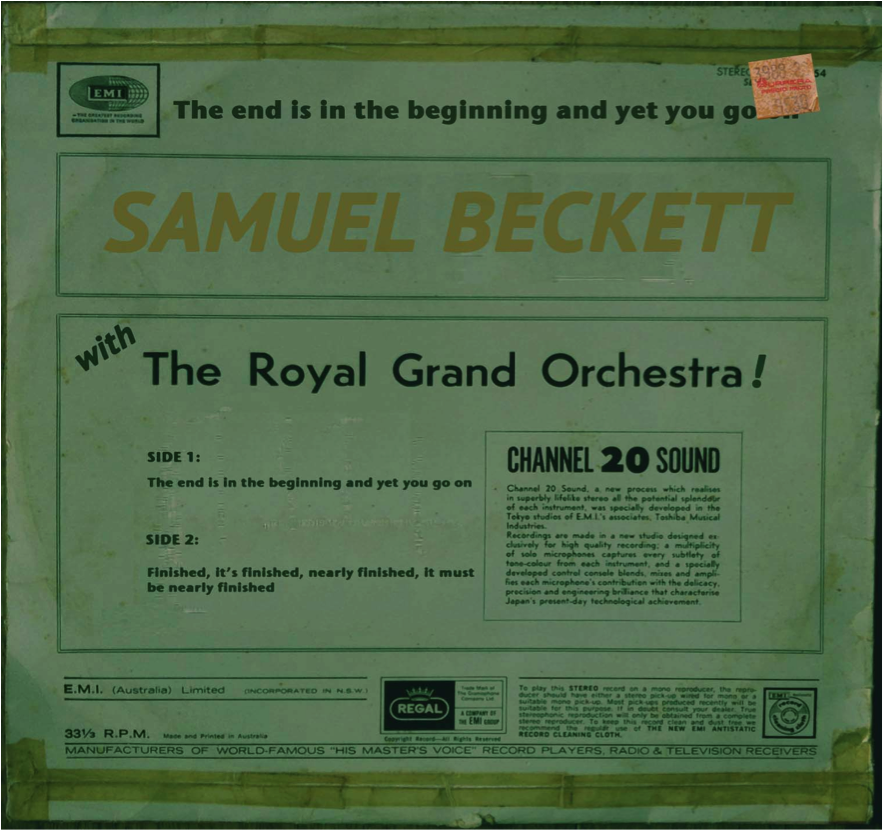

Ironically the iconic or absolute Beckett album, were such a thing to exist or even be feasible, would be a recording without sound (which effectively is what we have before us). Perhaps this sustained tacit is what the two tracks listed on the sleeve gesture towards, especially in their elongated phrasing. This being the case, playing it on a turntable would be a conceptual art gesture of critical reflection, a perceptual focus after Alain Robbe-Grillet after Heidegger on its thereness, the agon of being in Beckett’s theatre (Robbe-Grillet, 1989, 111). Or after Jacques Derrida, a recognition that writing is only possible when it is silent. Marcel Marceau had in fact recorded such an album in 1970, which consisted of 19 minutes of silence and one minute of applause (on each side). While music critic Lester Bangs included this title in his ‘Ten Most Ridiculous Records of the Seventies’ (coming in at number four), it suggests the end of one regime of signification – the doxa of acoustic space and the culture of orality – and the emergence of another: the improbable writing of silence. The absence of any attribution of a vocalist or narrator on the cover of The end is in the beginning and yet you go on is an undecidable and indeterminate aporia. To even speak of it, let alone write about it is, after Derrida, to ‘insist within the difficulty’ of its improbable materiality (Derrida, 2001, 61). The gramophone, we also know from Derrida, is inherently a technology of writing. Gramophony, he suggests in ‘Ulysses Gramophone’, is an effect ‘which records writing in the liveliest voice’ (1999, 276). Contrary to the voice, it was the writing of silence, as well as the desire to forestall it, that was Beckett’s lifelong quest. The end is in the beginning and yet you go on, a record sleeve without a playable recording, may be the twentieth century’s most vivid and compelling avatar of entropy. Norbert Wiener published his first study of cybernetics in 1948, a time coexistent with existentialism in France and Beckett’s earliest explorations of ending as an iterative process. (A truncated version of his aptly titled novella The End had been published by Jean-Paul Sartre in Les Temps Modernes in 1946.) Like writing on paper with a pen, once the stylus is placed on the rotating disk it is not progressing towards something, but temporarily putting off its completion. In the ‘Postscript’ to The Post Card Derrida notes that everything ‘seems finished when it begins’ (1987, 387). Friedrich Kittler, following Derrida’s lead, asserts at the start of his essay ‘Gramophone, Film, Typewriter’ that ‘even now, before the end, something is coming to an end’ (1997, 31). For Beckett the end was a figure for things taking their course and simply running out of puff, from desperate chatter fighting off silence in Waiting for Godot to the exhaustion of painkillers in Endgame. At the conclusion of The End (1954) the narrator, lying in bed, reflects on the memory of a story he could have, but didn’t tell – a story ‘in the likeness of my life, I mean without the courage to end or the strength to go on’ (1977, 95).

Pingback: number 4 – Bricks and Clicks