Café Beaurepaire resides snugly in a tree-lined cul-de-sac on the Rue de la Bûcherie in the fifth arrondissement. If not my favourite brasserie in Paris it is certainly up there, especially for its postcard glimpse of the Île-de-France, framed almost self-consciously through the horse-chestnut trees. On this particular afternoon I was less immersed in Parisian shadows and the frivolous play of light on dappled leaves than completely distracted by the object on the table before me – a long-playing record. This text is an account of the album’s discovery as well as a critical, archival and forensic study of the record and its cover art.

I stumbled upon it while scrounging through the riot of ephemera in a Left bank bouquiniste less than two minutes walk away, along the Rue du Haut Pavé to the Quai de Montebello. Amid teetering piles of old Paris Match volumes, musical scores, postcards and miscellaneous titles of Éditions de Minuit, I happened upon the LP. It wasn’t just any recording. It was an album apparently made by Samuel Beckett (or at least attributed to him) entitled The end is the beginning and yet you go on. What kismet or alignment of planets had converged with my visit to the French capital that April? As a Beckett scholar I had never heard of this inscrutable object, which the vendor gave to me for a few francs. He didn’t seem too fussed by it and said that he had never heard of the expatriate Irish writer, who lived most of his life nearby in the Boulevard St. Jacques. So with the giddy exhilaration of Marcel Duchamp finding a hat rack at the flea market in Clignancourt, I capered to Café Beaurepaire to revel in my find.

On a previous visit to Paris I had bought a copy of Beckett’s Molloy not far from where I found the record along the Quai de la Tournelle. At the time I thought this the grail of a lifetime, since it was the first 1955 edition published under the Collection Merlin imprint of Maurice Girodias’ Olympia Press, a notorious publisher of pornography and Dionysian writers, such as Henry Miller, Alexander Trocchi, Vladimir Nabokov and William Burroughs. And on another stay I had found Stolen Sweets by Paul de Kock (the nineteenth-century French author of saucy romance novels whose name appeals to Molly Bloom in Ulysses) as well as an 1890 paper-covered edition of Tristram Shandy. These literary gems made sense – their existence, reputation and value preceded them. But I knew absolutely nothing of the Beckett LP. Nor, for that matter, did anyone else, including its bookseller.

Cover art and album contents: a forensic analysis

The term ‘forensic’ may seem a little heavy-handed or dramatic in the current context. However I have appropriated the term from art theorist and curator Ralph Rugoff; he applies it to works of postmodern and conceptual art that, like the genre of crime-scene photography, represent a sense of the ‘aftermath of an event’ (Rugoff, 1997, 19). But there is nothing simple about applying such analysis to the kinds of installation art Rugoff describes. Not only do we seek to reconstruct prior events, such work invites us to trace ‘the play of promiscuously intermingled cultural codes that make reality itself seem suspect’ (20). Regarding the Samuel Beckett recording before us, such a critical mode of analysis is especially apt, since the object is enigmatic in its lack of provenance in either literary or musicological circles. The ambivalence described by Rugoff recalls Jacques Derrida’s critical reflection on the supposition of being able to dissociate knowledge from an event under scrutiny, since one is dealing with the ‘ambiguity of written or oral marks’ (Derrida, 1992, 282). But more tantalising with respect to Beckett – as well as the artifact bearing his name – is Henri Michaux’s description of the artist (quoted by Rugoff) as ‘one who, with all his might, resists the fundamental drive not to leave traces’ (Rugoff, 1997, 20).

The record

The disc is irreparably damaged. There is barely any evidence of the paper label, apart from minute fragments on either side. In addition to being warped with considerable scratching of the vinyl, there is clear evidence of water erasure of the grooves as well as deep accretions of what appears to be solidified mud or an abrasive aggregate of some kind (the vinyl may not even be the implied Beckett recording). It is tempting to see this detail as significant given its discovery so close to the Seine, from which it may have been retrieved. Even more apposite is its figurative affinity with the ‘Marne mud’ Beckett associated with the house he lived in at Ussy-sur-Marne in 1953, where he would retreat to write in quiet seclusion. However given the sound condition of the album sleeve it seems likely that the record itself is a replacement. So averring to Rugoff again, it is like a crime scene without a body.

The album sleeve

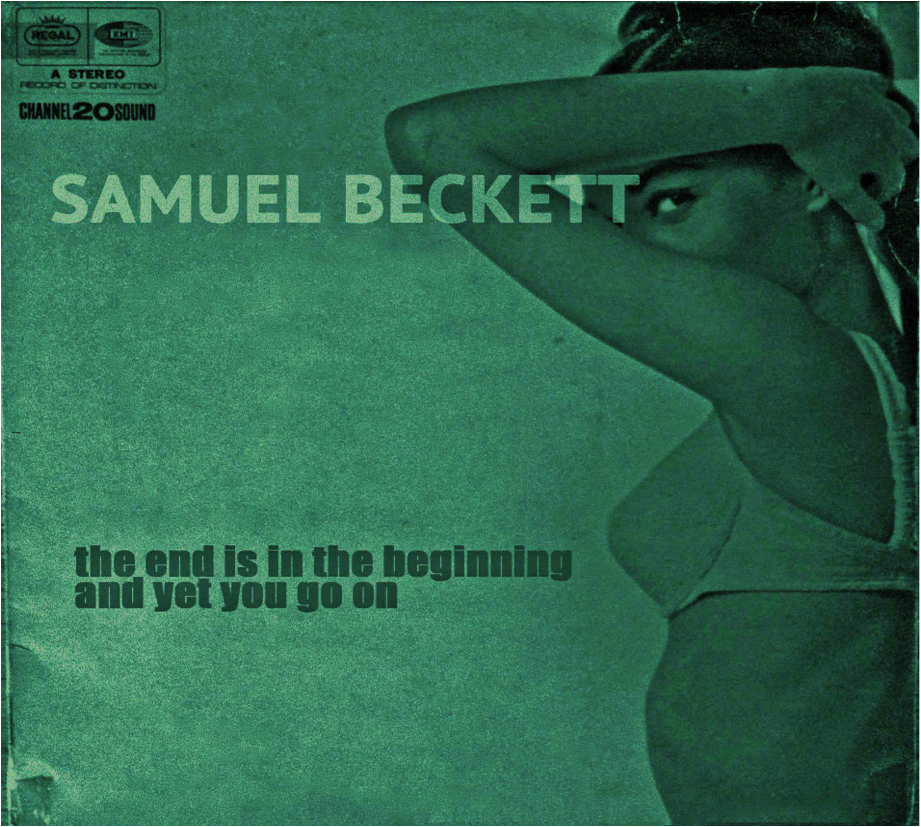

The sleeve and cover art are in excellent condition. It would seem to have been either stored carefully (perhaps in deference to its significance) or simply forgotten amid the bouquiniste’s ‘kipple’ (the colorful name for miscellaneous stuff coined by Philip K. Dick). There are no liner notes and – on the basis of the artwork – it is difficult to determine, or even imagine, exactly what the two tracks contain. The typography on the cover is spare. The title text is all in lower case and Beckett’s name is capitalised in a bold sans-serif font that bleeds into the dominant and unlikely image of a bikini-clad woman. The genre of the manifold image and cover art is consistent with what the writer and record archivist Benjamin Darling has called ‘the alluring ladies of vintage album covers’ (Darling, 2001). These sultry ‘vixens of vinyl’ adorned generations of easy listening, Latin and romance albums, what Darling describes as ‘bachelor-oriented records of the fifties and sixties’ (n.p.). These images were usually titillating and vampish, shot or staged in locations that ranged from nightclub scenes to bedrooms and exotic beaches. Titles such as Music to Make You Misty, Lush and Latin or Strictly for Lovers are indicative of the genre. The pose of the woman on the Beckett cover is certainly seductive: she stares directly at you from under her arm as she sensuously caresses her hair. The disjunction between Beckett and bikini babe couldn’t be more incompatible. However, a precedent for such odd bedfellows – existentialism and eroticism – occurred around the same time. In 1969 Beckett contributed his 25-second text Breath to Kenneth Tynan’s Off-Broadway erotic review Oh! Calcutta! Beckett’s original description of the mise-en-scène – ‘Faint light on stage littered with miscellaneous rubbish’ – had been changed by Tynan to ‘Faint light on stage littered with miscellaneous rubbish, including naked people’ (Tynan, 1969). Although Beckett offered the text of Breath (and was acknowledged as a contributor to the show on the bill poster, along with John Lennon, Jules Feiffer and others), he was outraged that Tynan included the reference to naked bodies and held back from taking legal action against him.

To make matters more confusing, the acknowledgment of the ‘Royal Grand Orchestra’ is vague (to say the least). Are the two tracks spoken word, accompanied by the orchestra – excerpts taken from one or more of Beckett’s works (in the manner of a festschrift)? Or are they abridged versions of longer titles? Perhaps there are no words at all, but rather musical orchestrations in response to familiar lines from Beckett’s texts? Does Beckett sing or speak them himself? There is no vocalist identified with the track listing, and he was known to have an elegant voice. The track titles are without question taken from Endgame, and specifically from two monologues by the play’s central protagonist Hamm and his companion Clov. The first (on side one) from Hamm, towards the end of the play as he is ‘warming up for [his] last soliloquy’ (Beckett, 1977, 49). The second track is a line spoken by Clov at the very start (12).

Readings of Beckett’s texts have been edited for LP recordings, though whether prior to or after the album under consideration it is impossible to tell – no date is visible on the vinyl pressing or the sleeve, nor is there any internal printed matter. Howard Sackler directed Cyril Cusack in 1963 reading excerpts of Molloy, Malone Dies and The Unnammable for Caedmon Records (TC1169). Caedmon recorded Happy Days, directed by Andrei Serban, in 1980 (featuring Irene Worth and George Voskovec) (Caedmon TRS366). Avant-garde composers have also been drawn to recording or publishing treatments and interpretations of Beckett’s texts, as well as composing music to accompany performances, most notably John Cage (They Come, 1987), Morton Feldman (Neither, 1997, ART 102), Philip Glass (Play, 1965) and Charles Dodge, who produced a computer-synthesised interpretation of Cascando in 1978 for Composers Recordings Inc. (CRI SD 454).

Pingback: number 4 – Bricks and Clicks