K/

When S. and I started to talk, the directions were endless, and sympathetic. What passed between us, over coffee and chai, in emails, in text messages, were the names of authors, books, artists. We were both mapping, many cartographies laid over each other, human and non-human. Struck by the ways the same ground could be covered again and again, never fully covered, uncovered, recovered. The Shards.

When the opportunity arose to work together, we suddenly poured forth not just our thinking, our reading, but the uncertain, unfinished directions our works were travelling. Mining towns, ghost towns. We both found ourselves in debris.

To find yourself in debris is also to find yourself in fragments. To ponder the very large, then swathe of climate, of extraction, of exhaustion, is to come back again to the tiny. That so far unending life of plastic, and before it of glass. To find underfoot the shards.

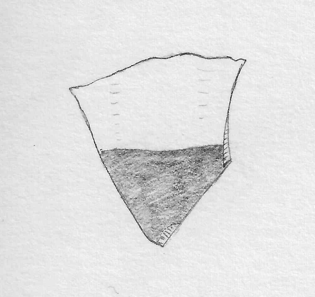

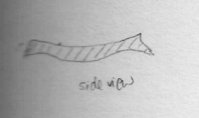

Sarina beat me to Hill End by some years. She’d been living with these particular fragments since 2010. I’d been walking and photographing and writing washed up rubbish in Leichhardt, Balmain, in Rozelle, in Iron Cove. When she showed me the sketch book in which she recorded the shards she found I was struck by the pieces of habitation – both in the physical objects discarded, but also by her recorded notes on where and when she found each piece. The habitation she drew upon was twofold.

A R Ammons wrote the long poem Garbage. One book is not enough. Besides, rubbish is personal – whether it is the rubbish we ourselves discard, or the rubbish that we come across in the streets, the gutters, the open fields. It is the packaging of who we are now, as well as the discarded identity of who we have been before. At Hill End, these fragments are part of where we have been: part of the gold rush that founded this town, the same gold rush that brought waves of immigrants hungry for riches, that displaced Indigenous peoples from their land, often ravaging that same land.