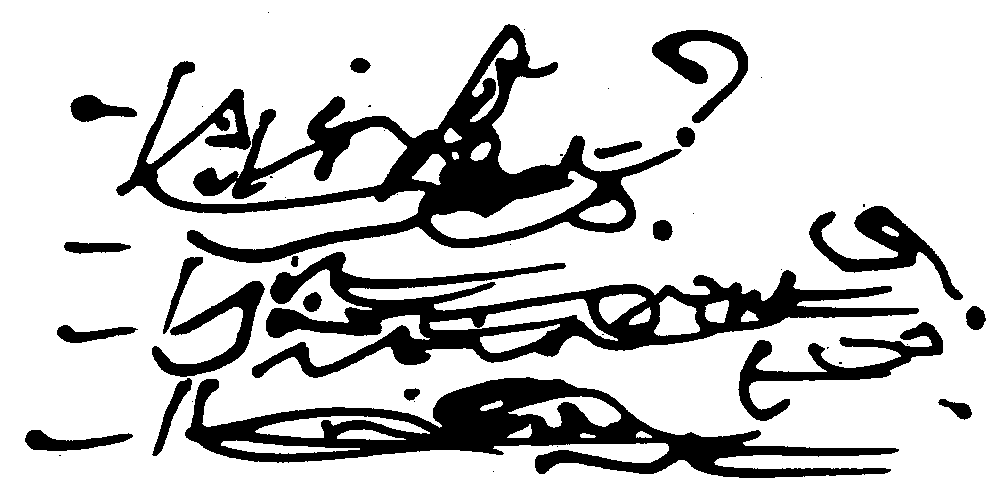

‘logogramme’ by Christian Dotremont from Logbook (Yves Rivière, 1974).

Growing up in Australia, I learned to associate the word ‘calligraphy’ with what is beautiful, perfect, virtuosic handwriting. However, there are other ways to interpret calli – the beauty – of handwriting. Punk calligraphy is my term for unhindered explorations of handwriting.

Even though I still find inspiration in the idea of punk, it’s post-punk music, which explores some of the landscape revealed by punk’s destructiveness, that continues to give me pleasure. Could one import the fertility of Melbourne’s ‘little band scene’ of the late 1970s into literary culture? In the case of poetry, if you strip it back to simple mark-making on a surface, and follow whatever logic emerges from that, you might end up in a new place, one that feels closer to your authentic self than a sonnet ever did.

The Belgian poet Christian Dotremont, a co-founder of the CoBrA movement, developed his own style of loose brush-written poems on paper, which he named logogrames. One description of them would be a European interpretation of Chinese calligraphy. Several examples were published in Logbook (Yves Rivière, 1974). The majority were written in French, although the example reproduced above is in English. Good luck reading it.

In the short text Signification et Sinification (published in CoBrA #7, 1950; an English translation posted at gammm.org), Dotremont advocated for creating a pseudo-Mongolian or pseudo-Chinese writing by writing something in your native language on one side of a page, then turning the page over and rotating it 90°, and then tracing what is visible of your writing quickly, moving downwards rather than left to right. What you get is mirror-writing, rotated 90°, drawn loosely rather than traced exactly – that’s certainly a punk engagement to another culture’s art if we are to take him at his word that he’s creating Mongolian writing.

The idea that illegible but freely written handwriting can be beautiful is at home in Chinese culture. As long ago as the Tang Dynasty (around 800 c.e.), a gentleman who chose the brush-name Zhang Xu practiced his particular specialty; a form of wild cursive calligraphy known as kuang cao shu, which was in some cases illegible to a Chinese reader, but full of passion. Zhang often wrote after drinking wine, and on occasion could not read his own handwriting the morning after a session.

If you know nothing about Chinese writing, perhaps a place to begin with an alternative form of calligraphy would be scribbles. Rhoda Kellogg, with the assistance of educators around the world, concluded that children of all cultures traverse identical stages of learning to make marks. In her book Analyzing Children’s Art (Mayfield, 1970), Kellogg identified 20 ‘basic scribbles’, ranging from dots, straight lines in various orientations and circular motions – which most children master in the course of learning to wield a pencil. As a child’s mental and physical capabilities grow, the scribbles are combined into more complex diagrams, combines and mandalas.

Scribbles can be assumed to be meaningless, and of little value. I argue otherwise: while you cannot write a logical, critical essay using scribbles, you can record certain states of mind and body more effectively than you can by words. The fast-flying scribbler’s arrow hits the bird. The composer of sentences has only written a single word by the time that bird has flown past. There seems to be a difference in level of intensity of scribbling, between tentatively testing a pen and making confident broad strokes to cover a large area. Some scribbles are serving a mental purpose, and have more of their creator’s personality in them. Other scribbles are made physically, with little of the mind involved.

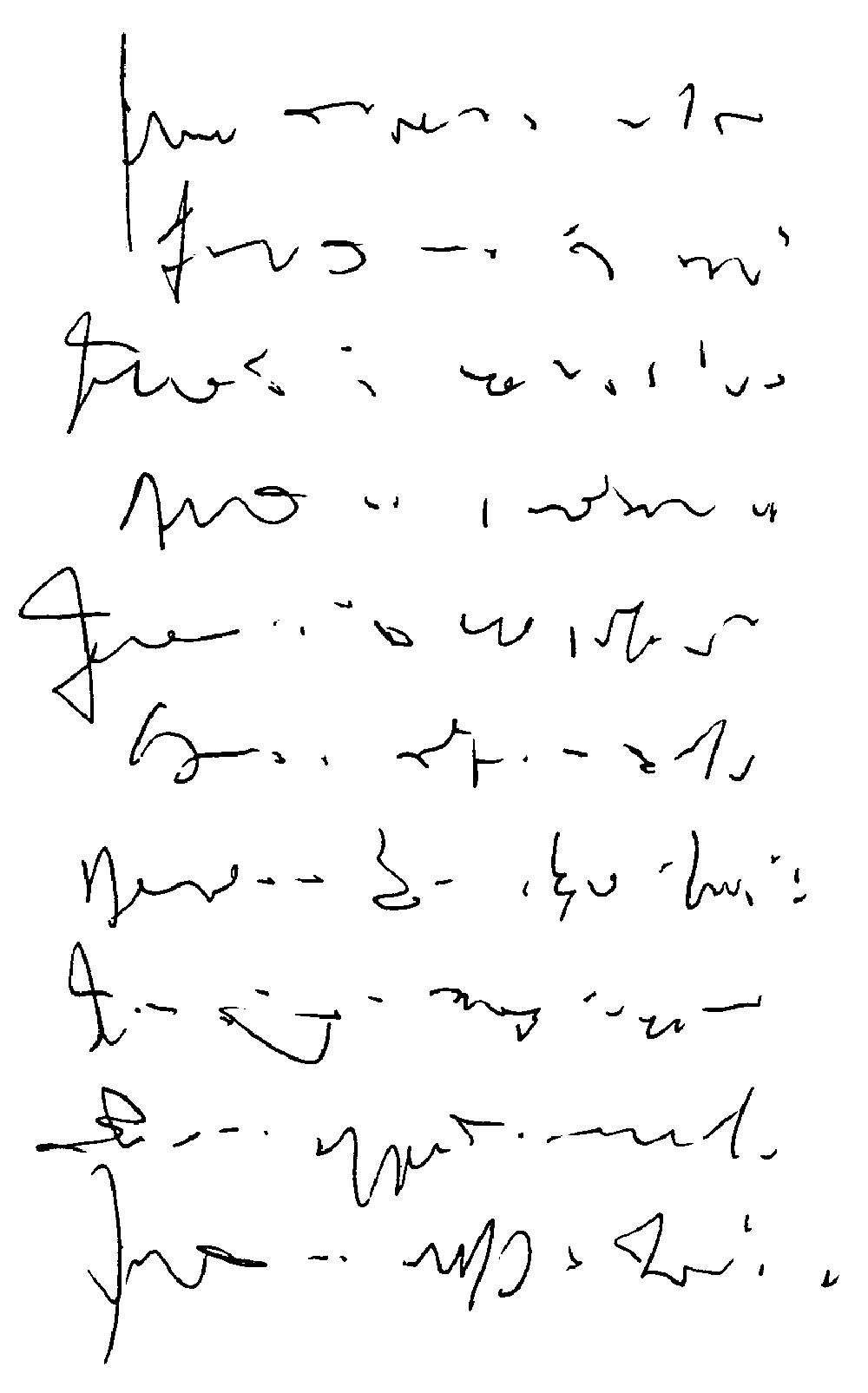

Seeing Jim Leftwich’s marks in Lost & Found Times #39 (1997), reproduced below, got me thinking. I’d never seen anything like them before, especially not in a poetry magazine. They looked like unfinished snippets of handwriting.

Marks by Jim Leftwich from Lost & Found Times #39 (1997).

At Leftwich’s request, I quote his recollection of how they originated, and as published in his text Subjective Asemic Postulates, part 2 (2015):

My first explorations of quasi-calligraphic faux writing came the morning after a particularly intense experience of taking what Terence McKenna called a ‘heroic dose’ of psilocybin mushrooms. I had experienced a complete annihilation of the self, and not one of merging harmoniously with the universe, rather one of being ripped apart, as if in a ritual sparagmos. The next morning I was sitting in my car and I started for the first time to write lines of illegible fake writing. It felt as if I were being guided to do this, as a kind of healing for the night before.