Composition by Mirtha Dermisache from intermediales (Manglar, 2005).

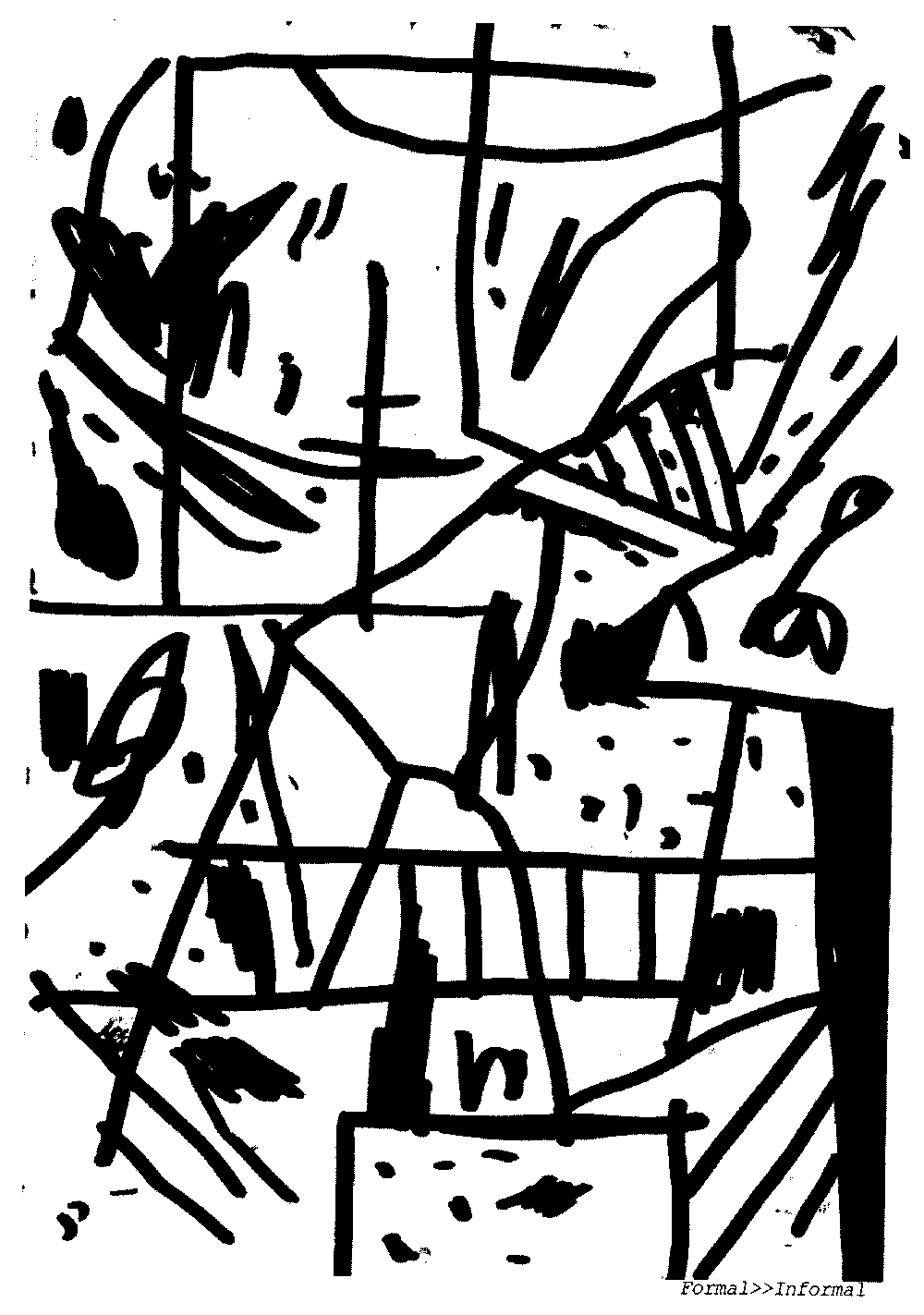

Marc van Elburg is an artist, publisher of zines and proprietor of Zinedepo in Arnhem, Netherlands. In zines such as Rover Idiomatic (2012), he treats his arm and hand as a kind of plotting machine controlling a marker. Rather than drawing or writing in a comfortable way, van Elburg applies concepts analogous to computer programs, using ‘quasimodes’ such as ‘sparse’ (including ‘formal’ and ‘informal’ modes) or ‘dense’ (including ‘global’ and ‘local’ modes), ‘shifting loci’ and ‘thresholds’, to generate compositions that hint of noise and rationality. In more recent zines, van Elburg presents what could be described as punk theory. For example, in Autosomatix: Programming with Grawlixes (2013), he offers an explanation for the forms of the swear word censoring symbols used in comics.

Drawing by Marc van Elburg from Rover Idiomatic zine (2012).

By email, I was introduced to Marc van Elburg by his friend Wilfried Hou Je Bek, whose the crystalpunk manifesto suggests that growing salt or sugar crystals in your own home is a 21st Century form of punk creativity. Earlier, Hou Je Bek conducted experiments such as algorithmic walks, in which you follow an instruction such as ‘second left, first right’ while walking through an urban space, until you get stuck in a loop, and revisit the same intersection, at which point you invent a new instruction. This form of urban exploring is similar to – but achieves slightly different results from – the Lettriste dérive, or drift, a form of psychogeographical exploration given publicity in recent years by Will Self.

Producing freestyle calligraphy is an achievement, but how is a reader meant to receive it? Without words to distract us, scribbles or loose illegibles can affect us in a similar way to music. We might like or dislike an example, be bored by it or interested in it. For some, this reaction is enough. If you like a piece of music, you don’t always psychoanalyse yourself to understand why. The art historian James Elkins’s book The Domain of Images (Cornell University, 1999) divides images according to function, and considers a page full of sentences to be a sub-species of image. Elkins encourages us to ‘take the temperature of a reading,’ in order to decide whether an image contains legible words, or some other form of notation. For many, after a split-second observation, a scribbled composition is filed under scribble – therefore considered useless – and that person’s attention immediately moves elsewhere.

The artist Tom Kemp said you could paint a copy of a piece of fruit, or money, or a building, and all you get is a copy. But if you copy writing in a painting, you get brand new, fully functional text. To outflank this seemingly unbeatable observation, I propose to you, reader, the experiment of quickly and carelessly sketching an existing piece of writing. If your sketch is too faithful to the original, make a simpler subsequent sketch of your first. This may give you a punked up piece of sub-writing, something more primitive and general than legible writing.