Image courtesy of The New Yorker

Wherefore

a grave, deliberate

Glissando of the cup towards the rainbow’s end:

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ

DJ. What’s all this?

JM. Looks like the alphabet.

Gabr. THE NEW MATERIALS, YOUNG POET, FOR A NEW FAITH:

ITS ARCHITECTURE, THE FLAT WHITE PRINTED PAGE

TO WHICH WILL COME WISER WORSHIPPERS IN TIME

(Merrill, The Changing Light 446)

Like some piece of technicolour cover-art from a 1950s mystery novel, James Merrill’s Stonington apartment loomed in the background as I stepped out of the gutter-snow and onto the street. I was wearing a bright red coat; the apartment matched the slate-blue winter sky. From the outside, the poet’s house felt as gorgeous and twee as everything else in this tiny – dare I say quaint – fishing village. The crab chowder I’d just consumed in the café three doors down had been hearty and yet watered down to perfection: not too flavoured, not too flashy, yet rich – an echo of the village values. Once inside the tower house, however, Merrill’s still-pervading spirit unfurled its colourful stripes with candour. The experience of standing in Merrill’s house was hyper, bizarre, other. The apartment could never have been real, what with all the separation of units – the oceans and time between me-now and him-then. It couldn’t possibly have been standing as he left it: preserved like some mausoleum-museum nobody ever visited, stilled and silenced since Merrill had died in 1995. As an Australian poet and research student with no real connection to any American poetry canon, it seemed almost blasphemous that I should walk amongst the ornaments, touching the faded chairs where JM and DJ once played with the dead.

I discovered the James Merrill House in stages. Prior to arriving at his house, I had never read any biographical material concerning Merrill. Yet through my reading of his often-veiled autobiographical poetry, I already felt I had an ancient, secret knowledge of his living space. The epic long-poem The Changing Light at Sandover unfolds its secret titbits of personal information slightly, almost sideways. Merrill’s revealing of his home throughout the long-poem is controlled, yet the subtext is wild, like deliberate whispers in the night. The snippets of the poem that evoked Merrill’s domestic abode always felt to me like a quiet rumour, shared just between friends. While I was now physically leaving my footsteps behind in the sidewalk snow outside the Water Street house, I had already arrived inside many times in my thoughts, while reading The Changing Light.

Wandering about inside James Merrill House and photographing his personal flotsam and jetsam, I knew I really shouldn’t be so familiar with the space. In fact, when I sat myself down on a cane chair in the tower room, my guide very politely asked me to stand. Perhaps I was too at home in the tower room, the one ‘the newly dead’ Wallace Stevens would mistake as an ‘alcove in the Baptist church’ (Merrill, CLS 5), yet here I was and there it was, out of the poem and in to the actual – not so ecclesiastical – encompassing me. Gaston Bachelard, in The Poetics of Space asks, ‘Is there one among us who has not spent romantic moments in the tower of a book he has read?’ (25), and I admit I had often become adrift inside the looming fortress’ ‘unforgettable intimacy’ (24) while reading The Changing Light. Perhaps it wasn’t the outrageous cosmological claims of the long-poem, but instead Merrill’s intimate descriptions of his home and domestic life, scattered throughout its pages, that drove me to investigate the poem further. I had unwittingly spent what must amount to days (it’s a rather long long-poem) dreaming myself inside this curious New England home, envisioning sitting down with the poet and an Ouija board under the ‘pressed tin dome’ (Merrill, CLS 5). So many of the poem’s secrets were unfolded at the round table in the tower room of the ‘old eyesore’ with its ‘witty shade’ of paint: ‘now watermelon, now sunburn’ (Merrill, CLS 5). I can now attest to the fact that the colour of the dining room walls is quite beautiful, if garish. When I finally found myself sitting inside the Water Street apartment in Stonington, CT, on the other side of the world, in a winter more cold than I could imagine, I knew the place like a familiar character from a favourite novel, or a favourite Aunt – someone with whom I regularly took tea on a Sunday afternoon.

Sitting at my desk in Newcastle, NSW, a couple of weeks prior to my visit to the US – 15 years after James Merrill’s death and 30 years since the publication of The Changing Light (it was completed not long after I was born) – I wasn’t sure why I was reading the frustrating long-poem. What I needed at the time was to ground my own poetry in image, to centre my wandering, almost cosmological, expansive poetics safely inside the boundary fence of the simple lyric. While somebody might have once mentioned Merrill’s book in reference to my (albeit eclectic) more serious studies, I most likely came across it myself in some quasi-scientific/religious book on angels or black holes or both (the title of which I conveniently can’t remember, no doubt out of embarrassment). An endlessly contradictory epic that encompasses five hundred and sixty odd pages, The Changing Light comes on like an occultist apocalypse in which Merrill converses via an Ouija board with the dead, with fallen angels, archangels, and even God (known as ‘GOD BIOLOGY’ (113)) himself. Merrill, it is revealed, is writing (or transcribing) the epic because it is his ‘V-work’ (161) – a sort of life calling: to create this farrago that the fallen angels refer to as ‘POEMS OF SCIENCE’ (109). He is divinely called on to share his findings (which amount to the heavenly beings’ previous and future plans for humanity) with the literary-minded poetry readers of the future (yes, I am also thinking of the Raelians or the sci-fi religion of Hubbard). Even to my ready-to-believe-in-anything mind, The Changing Light’s prophetic intention came on a bit strong. Although I, too, have a whimsical prophet-poet inside me, Merrill’s reluctant role in the salvation of the universe was almost too much. At first, I took it to be a dramatic feint, a hyper-reality coated farce. And perhaps it was.

It is best to heed Timothy Materer’s warning when he writes, ‘Is The Changing Light trilogy an epic, mock epic, or anti-epic? Applying any critical category to Merrill is dangerous’ (Apocalypse 2) – but for the purposes of this essay, I can’t escape trying. The long-poem, apparently dictated by the many voices of the dead and other spirits, contains a multi-layered eschatological worldview centred on the threat housed inside the atom – and a salvation that may or may not (the chief spirit, God Biology, seems ready to give up at any moment) come from a type of elitist genetic engineering, or soul-cloning, scheme. The reader might logically assume that the epic’s tone simply has to be largely tongue-in-cheek, and certainly driven by a large grain of salt. Poetry written in the first person can provide a perfect theatrical space for farce and theatricality: inside the assumed truth lies an apt arena for invention. Almost immediately upon reading The Changing Light, many continuity issues within the poem’s doctrine (messily outlined, stated forthrightly and then taken back pages later) become overwhelming. Still, this often paradoxical, sometimes confusing epic somehow managed to lock on to my bones and draw me in, just as I was trying to avoid its haunting call. This long-poem, even with its bat-angels and Unice the unicorn, in the style of a Gnostic, theosophist, or even Alistair Crowley-inspired holy text, seems to believe in itself, thus inviting one to believe in it. While I was attempting to ground my own ephemeral poetry in simple description and image, Merrill’s apocalyptic, spirit-dictated fission of air and light was pulling me back to familiar territory: that almost-millennial, certainly playful, almost pop-cultural – certainly pop-scientific – miasma from which I was attempting to distance my own poetry/self.

What

To give an idea of just a few of the difficulties to be faced when reading The Changing Light, both the physical appearance of the text and the multifaceted layers of voice need to be discussed. The Changing Light is a fusion of poetic asides and direct Ouija board dictates jotted down by James Merrill (the SCRIBE), but pointed out by David Jackson (the HAND), who acted as a channel for the multifarious voices of the Ouija board spirit world. The long-poem is presented as being derived from actual messages received from the spirit world, and initially that means the dead, including the very famous dead (from Akhenaton to Gertrude Stein). These spirits often dictate direct messages, while at other times Merrill works his poetic magic over the transmissions in order to make them more palatable. As the work progresses various heavenly and/or hellish spirits, and even a god named Biology, and his counterpart Nature, also chime in and direct (via the archangels) a series of lessons about the progressions of the universe and the history of humanity.

The Changing Light is presented as a trilogy (made up of three increasingly opaque books of poetry) with a coda at the end. The first book, The Book of Ephraim, was begun in the 1950s but published in 1976 as part of Merrill’s collection Divine Comedies. The second volume of the series, Mirabell: Books of Number, quickly followed the first and was published in 1978. The third instalment, Scripts For the Pageant, arrived in 1980 and the trilogy was finally collected together (along with the coda The Higher Keys) in 1982 as The Changing Light at Sandover. The epic long-poem was adapted into a screenplay in 1990 for the film Voices from Sandover at the prompting of Merrill’s intense fan (and lover at that time) Peter Hooten; but as far as I can tell, most serious critics prefer to pretend that this never happened. I found it impossible to access a copy of the VCR tape made of the play, though I can see that from stills found on Roger Bourland’s blog it was a poor, effects-driven affair. The latest, most beautiful edition of the (print) long-poem, the one I purchased at a glamorous bookstore in Greenwich, CT, contains also the script for the controversial film Voices from Sandover, following the coda at the end of the trilogy; so I suppose it is now a five-book masterpiece: that is, a prolific pentalogy. It seems this already insanely long long-poem just never stops growing, even after Merrill’s death. Its mysterious expansion is just one of its many endearing quirks.

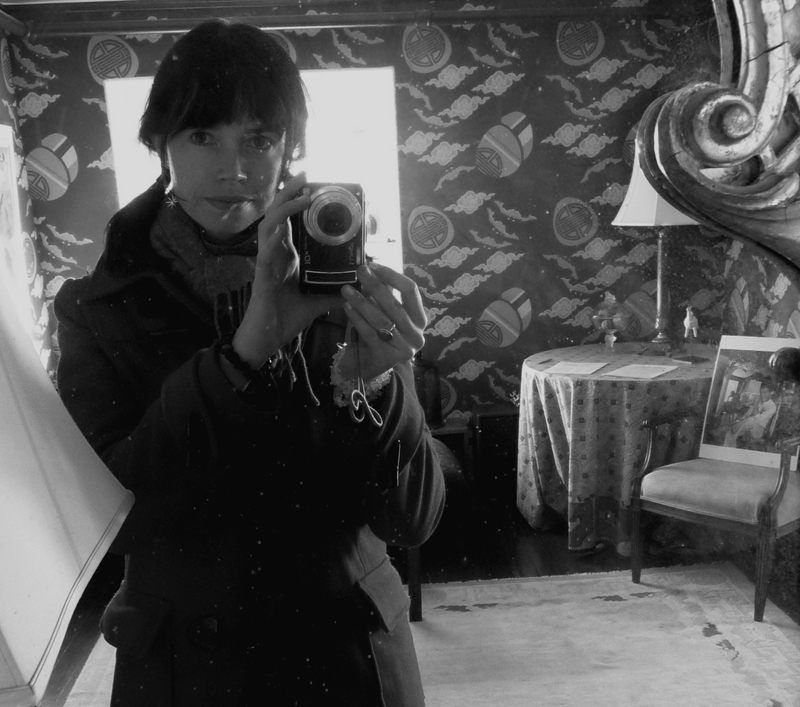

James Merrill, from beyond, sneaking into Ivy Ireland’s mirror selfie.