For me, as for many of my writer-friends, Dransfield was a key entry point into Australian poetics. This hoo-ha has collided with some of my own recent thinking about the legacy and relevance of Dransfield today, more or less half a century after his last poem was written.

I had the fortune of being introduced to Dransfield by Pat and Livio Dobrez as an undergrad at the ANU. I’d enrolled in a lit theory course, and each week twenty of us would cram into the light-filled office corner office they shared. One week, Livio snuck Dransfield onto the reading list. At the time, I had no idea that the two had respectively published the two major texts on Dransfield: The Many Lives of Dransfield (Pat), and Mad Parnassus Ward (Livio). But I do remember reading ‘The Technique of Light’ and loving it.

Then I suppose I forgot about him for a while.

More recently, in late 2011, I took a trip on the Countrylink Express, stocked with my iPod, enough change for a sandwich and a Devonshire tea from the buffet cart, and a copy of UQP’s Michael Dransfield: A Retrospective, edited by John Kinsella. My intention was to allow myself a lengthy stretch of time to really engage with one text, something I take the opportunity to do much too rarely. Dransfield was chosen because I’d been doing a lot of thinking about ecopoetics, and I’d been listening to a lot of Australian post-punk, and I just had a hunch that these three things would spark off each other somehow.

It was an atypical Melbourne morning: damp foggy and cold – a precise kind of complement to Dransfield’s poems. As the train set off through the drizzle, I suspected I was about to become haunted. And I was right.

At the start, well-caffeinated, I jumped at Cosmopolitan Dransfield, found in poems like ‘The City Theory’, where:

next door, they make their coffee for you,

know its ingredients, the cup you like, and

what to say to you; they know your symbols; to learn this

shatters you.

In this poem, Dransfield articulates the struggle of maintaining a rich internal life in a personable city whose entreating nature slaps at one’s ego. It was a gripe I could relate to.

But by mid-morning I was eating Devonshire tea, and reading ‘Birthday ballad, Courland Penders’, properly settled, and properly fixed on these lines:

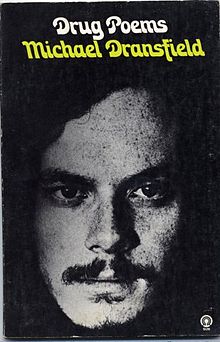

Food does not rate a mention in Dransfield’s oeuvre, which is not to say he was absent of hunger, craving or vice: he is often glossed as Australia’s iconic drug-poet, and the drug experience is certainly flecked through many of his poems.a needle spelling XANADU

in pinprick visions down your arm

what of nostalgia when

the era you grew with dies

Yet Dransfield isn’t fundamentally about the drugs. He is more about gradients of exile, searching for a home or place, or at the least the glint or smacking weight of concreteness.

‘Hunger repletion musick fire’ Dransfield writes in ‘Birthday ballad, Courland Penders’. ‘The stimuli of hollow days’ (it’s at this point I smear jam across the page). What I think he means is that it can be really difficult to keep kicking on when you know you’re atop the crumbling tenement of history:

towards the top I let go

the staircase and fall breaking

the day into space and the scene

into components noticing everything (from ‘Technique of Light’)

Dransfield takes nothing for granted, even in boredom, or exile (read: rehab). But this also seems to be his greatest conflict. He can’t help but keep the skull beneath the skin in constant purview.

This reprint edition of The Streets of the Long Voyage was first published in 1972 by the University of Queensland Press in their Paperback Poets series. This was Paperback Poets 2.

Dransfield of course died young at 24, just prior to the cultural postmodern surge his poems were beginning to predict. His early death is a fact both poignant and profound to our subsequent mythologising of his work. Just like the creation of his own Courland Penders, Dransfield encourages us to project onto him our own kind of place-making. So perhaps we can say his relevance lies in the imaginative potential his poetry continues to spur.

Towards the end of the trip I switched on The Go-Betweens while reading.

‘Dust from the creek covers the sky’, sang Grant McLennan.

‘Before rain; dust nothing else’ Dransfield replied.

I wondered (I continue to wonder) what Dransfield would have thought of The Gos. I wonder what he would have thought about that whole post-punk generation: The Triffids, The Laughing Clowns, The Church. They share a similar clammy aesthetic, a similar ecological vibe.

In his essay ‘Michael Dransfield’s Innocent Eyes’, Derek Motion discusses Dransfield’s a-temporality. He notes that ‘Dransfield sees what he likes, in the way he likes, and then knits his field of vision into an a-temporal firmament’.

This feels right to me. That day, as I stared out at a grim rainy countryside, reading poems like ‘Like this for years’ I felt Dransfield’s restlessness, how he rolled over things like a cloud; making poems which appear solid only from a distance:

and when the waves cast you up who sought

to dive so deep and come up with

more than water in yr hands

and the water itself is sand is air is something

unholdable

I think he’d been travelling as a ghost long before he died. Kinsella too suggests as much, prefacing the collection with this quote from Dransfield circa 1969: ‘I’m the ghost haunting an old house, my poems are posthumous’.

I don’t quite know how to pin down what it is that has made Dransfield so keenly beheld by me and many of my friends, though I think that all of this gestures to it, ‘a welter of corollaries’. Perhaps it’s his youthful temperament, perhaps this is beside the point: his is a poetry that speaks forward, into post-punk, and ecopoetics and beyond. And to my mind, poetry with impetus like this is the only kind worth anthologising.