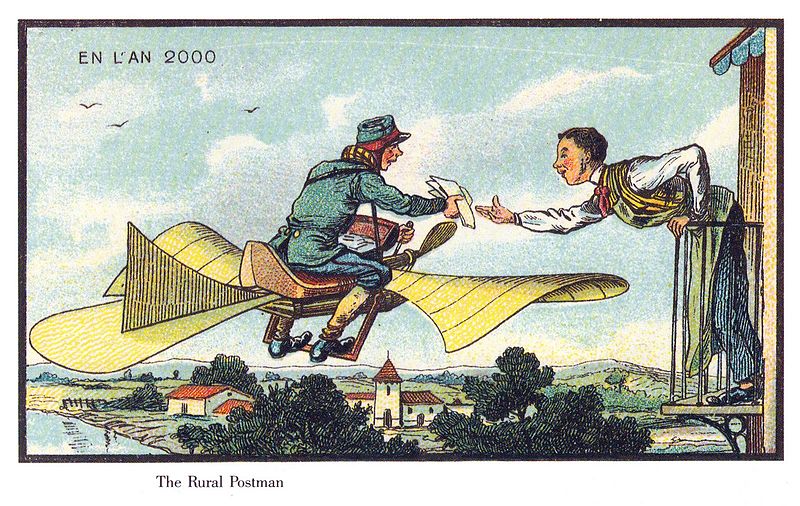

The theme for this issue arose from a chance encounter with a flying machine and a Frenchman. The illustration above, by Jean-Marc Côté, is one of a series commissioned to be printed on cards for cigarette and cigar boxes at the 1900 World Exhibition in Paris: the task of the illustrator was to imagine what life might be like in the year 2000. In 2016, Côté’s images are hardly more than quaint curiosities, sepia-tinted windows onto the past. Science fiction, we are reminded, is itself somewhat of a retrograde genre and the central paradox it speaks is that the future is always already retro; it, too, is subject to the effects of age.

Several months after this first encounter, on a long-distance flight across the Pacific, I read about another Frenchman and his flying machine. In Wind, Sand and Stars, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry writes of the experience of being a pilot, thousands of feet in the air, delivering mail for Aéropostale and dreaming about the points of light below – each an island of human habitation in a dark wilderness, each an entire world, an enclosed capsule, yet yoked together precisely by the fact of a man in a plane delivering mail. Though we are a long way from Côté and Saint-Exupéry, we have perhaps not come so far: machines overwhelmingly remain, for the most part, tools and allies; helping to conquer distance, the weather, disease, tragedy; carrying signals and desires between points of light.

To think of future machines is to think about time, about the shifting and contested boundary between humans and machines, about the future as a collective hallucination – a region that perpetually recedes and advances like a mirage. The halls of science fiction are populated with novels and films, but these only take us only so far – as genres they are, by convention and more often than not, compelled to fill in the gaps between what we believe we know and what we imagine; they are bound by the need to make sense, to explain themselves. Poetry is a form that is eminently suited to leaving the gaps well alone, or allowing them to multiply: poems do not need to explain, or make (mechanical) sense to either their makers or readers; they follow neither the laws of cause and effect nor expectations of sequence. This is not to say that poetry is devoid of sense, only that it allows for the unaccounted and unforeseeable.

The title of Phillip K. Dick’s novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? asks us to consider the part that dreams play in the drama of being human. To dream is not only to imagine but also to desire, and to desire so intensely that we seek to turn the dreams of sleep into waking realities. One answer to the question of what, besides chemicals, besides electrical impulses, besides biology and evolution, makes us what we are, might very well reside in the space between the imaginable and the possible; a space that poets, and all artists, have traversed frequently and patiently over the course of centuries.

Another answer may be in the awareness and experience of loss and death. The heart, an organic engine, has a limited lifespan – it beats a certain number of times and then falls still. It is this inevitable loss, held in trust by the unique and perishable body, that seems to give human life its precariousness and its preciousness. Yet the problem of finitude is not ours alone: if we decompose and return to soil, then machines rust, crack, become scrap. Stars consume themselves or are consumed, galaxies collapse. In the very act of existing, of persisting through time, everything is wearing down, breaking down, day by day. Nothing is, in the end, eternal.

In the face of this knowledge, what can we do but persist? And how, today, can our persistence be separated from that of the machine? The future (and the present and the past) is filled with machines: counting machines, music machines, memory machines, war machines. They are not only parts of ourselves but also mirrors – if their successes are ours, their faults are, too. And if we fear what they might become, and the uses to which they might be put, it is because we know what we have been and are capable of. When we write of them, we are always also writing of us.

My intention with this issue of Cordite Poetry Review was to evoke, but not limit poets to, the realms of science fiction. The strength of this genre has always been in its emphasis on invention and imagination: I hoped for, and received, submissions that approached the theme obliquely. The poems here engage with fictional and real locales, some dialogue with the past, some treat with the language of code and others with language as code – for language is itself a machine and poets are particularly well placed to put it through its paces. In this issue are light thieves and ICU wards, crystal balls and mechanical hearts, ghosts, blazars, bodies in cars, retired terminators, white linen jumpsuits and factories in the sea. Collectively, they stand as a record of our dreams of future machines now – dreams that, at the moment of their dreaming, begin to decay.

Thanks to the poets for their arresting visions, and for being willing to move into what may have been unfamiliar territory. Thanks, too, to Kent MacCarter – a formidable poet himself – for his patience, good humour and support through the guest editing process, and his tireless work promoting Australian poetry over the years.