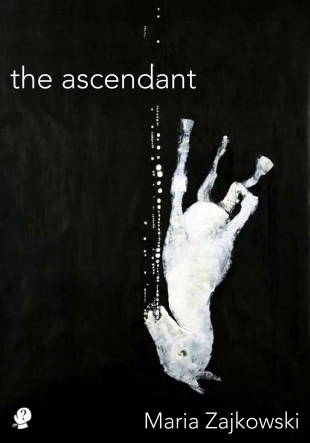

The Ascendant by Maria Zajkowski

Puncher & Wattmann, 2015

The challenge for any author in writing a book about death is to somehow make the subject seem both itself and new at the same time. Death is familiar, but poetry about death should not be. A good poet will give death impact without slipping into easy sentimentalism. Maria Zajkowski – winner of the 2011 and 2012 Josephine Ulrick Poetry Prize – undoubtedly succeeds in this regard with her debut collection The Ascendant, creating a vulnerable portrait of the poet through evocations of possession and loss.

The poems in The Ascendant appear simple in their composition and are often no more than a page or single stanza in length. The line is brief, comprised often of only one phrase or clause, and punctuation is used sparingly, as are descriptions of colour. But the poetry does not seem desaturated; Zajkowski’s minimalism does not drain her work’s vibrancy. Rather, the effect is that The Ascendant appears unadorned – it is as though the poems seek to channel some inner trace of the soul onto the page. Zajkowski’s talent is in her ability to pare away the pretense of her poetry to produce work that is at once sensitive and strong. Though the poems seem simple at a glance, they contain within them a complexity of feeling and an honest intelligence that transcends their form.

Zajkowski’s use of the first person plural engages the reader more intensely in the emotional weight of the poetry, and allows the complex interplay of togetherness and separation to be immediately recognisable on the page: ‘I’ve forgotten if you are me / or I’m you / We switched bags somewhere’ (‘The fence is gone’). Likewise, the roles of the deceased and the living become interchangeable in the book’s fragmented narrative. In some poems it is the speaker who is dead – ‘I have been buried turning away’ (‘Underland’) – and in others it is the spoken to: ‘it’s sixteen weeks since we buried you / and the watching is just comfort now’ (‘No word’). Still, in others, it is the speaker and the spoken that are united in death: ‘trees like us / are already dead’ (‘The problem is’). Nothing is ever settled in The Ascendant, and Zajkowski will deliberately contradict herself in order to better convey the indeterminacy and vulnerability that make up the emotional cadence of her poetry. Thus she writes amusingly in ‘The white butterfly’ that the ‘The white butterfly is / the brown butterfly / who is the moth,’ who is the tree and so on. Or that ‘wine is not really wine / but breath that forms to unform’ (‘The use of regular forms’).

By developing a network of motifs throughout the work, Zajkowski’s poems appear to communicate with each other in a way that makes the book feel more like an extended suite of poetry rather than a collection. Stars, angels, trees, holes, arrows, and wounds among others appear and reappear, enacting thematic concerns of ending and revival. There is a vague narrative connected by the returning orbit of these motifs, telling in glimpses a story of loved ones both separated and drawn closer by death.

The Ascendant’s most compelling images involve a confluence of the mundane, the personal and the cosmic. In the following lines of the poem ‘Love is a selfish life’, the focus of the line seems to zoom in and out like the lens of a camera, sliding effortlessly in scale from the minute to the grand and back again:

This work is reminiscent at times of MTC Cronin, who, with Peter Boyle, provides the blurb to the collection, writing that Zajkowski’s poetry ‘reads like something no one has ever said before.’ This is certainly true of the best poems in the collection, such as ‘Bison grass’ or ‘This is not the silence I imagined’; poems that seem cumulative in their development, each stanza building upon the images of the previous stanza until the poem completes itself tidily in the final line:

Or, conversely, the poem will build to an inconclusive end, unable to resolve itself with certainty, as in the final lines of the poem ‘How many cats are you’: ‘somewhere else / and here is nothing / but nothing but.’ It is a risk Zajkowski takes in this collection to acknowledge the boundaries of poetry, the limitation of words to form a complete image of death. But in so doing she allows each poem to retain its undecidability. Every line illuminates the next while simultaneously containing something of the unknowable.

Zajkowski’s collection is at its strongest when it is aware of its own ineffectuality. The effort to comprehend death through words is ultimately without hope, but it is this conceit that motivates her poetry. Failure and disappointment, both of words and of the people who speak them, is another axle on which the poems in this collection turn. Hence we lead ‘ignorant lives’ with only ‘a mist of explanations’ to enlighten us (‘The beginning and’; ‘All that is written is blank’).

Despite its ubiquity, death never fully unveils itself in The Ascendant, but remains a dark ellipsis, residing someplace beyond the poet’s reach, an unanswerable question. Yet Zajkowski is not a nihilist and the relevance of her endeavour to know death through language is no less urgent for its impossibility. She writes ‘it is a wound to let a wound / fall unheard’, confirming her commitment to her art, her need to express the inexpressible (‘It must have a name’). She writes that ‘into death’ she is ‘repeating the unsayable’ (‘Through the night wave’). The theme of repeating the unsayable, of speaking in silence, encapsulates both the essence of Zajkowski’s poetry and that of its subject. Death is both obscure and clear; it is trauma, but also relief from pain, just as Zajkowski’s poetry is at once testimony and confession, pathos and bathos. Every poem leaves an open end, reminding us that death itself is a form of anticlimax. The poems in The Ascendant affirm death’s ultimate strangeness, its quality of being other and commonplace at the same time, and offer unfiltered moments from the poet that transfix the reader in their intimacy and imagination.