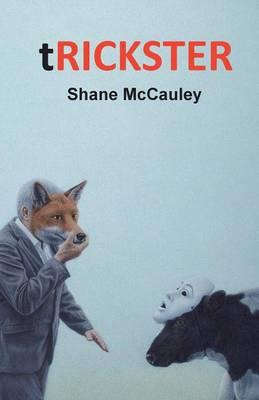

Trickster by Shane McCauley

Walleah Press, 2015

It is something of a paradigm in literary criticism (poetics included) to couple West Australians with place. Of late Tim Winton and John Kinsella have occupied this ground, but it is there in thinking about Randolph Stow and Dorothy Hewett and many more besides. It was Winton, after all, who wrote – ‘we come from ‘the wrong side of the wrong continent in the wrong hemisphere”. The place, thought of quite literally as location, is simply ‘wrong’, meaning not quite right, meaning askew. This is to say nothing of the spirit here, or how, for a great number of people (some Noongars and others included), this always was and always will be the very centre of the world.

West Australians don’t simply come from a place; they have a place, which, at the level of identity, is connected to the apparent authenticity of the rural, of isolation, of frontier. It is also in co-operation and competition with Indigenous Australian conceptions of connection to country. It is firmly located despite being in Michael Farrell’s words ‘unsettled’.

Place looms as a central concern in Shane McCauley’s Trickster, for in this book there are poems connected to identity and geography as constitutive of being and self. It is not the unsettled rootedness of Angelus or Wheatlands here, but a great variety of un-rooted settlement in locations in Asia (mainly Japan) and Europe (mainly Italy). McCauley is an erudite tourist. If he is not a sibling of the traveling John Mateer, then he at least bears what Wittgenstein would call a ‘family resemblance’.

McCauley tends to favour a plain-spoken lyricism that focuses in an Imagist tradition on the exterior world – society, nature, experience and phenomena. We get very little sense of his feelings, but a great deal of perceptive portraiture of bourgeois still life. There is, of course, a speaking I (see ‘After Hwang Jin-Yi’ for example) even as the eye is steadily looking ‘out there’. In ‘Midnight on the Isola Tiburina’ McCauley writes:

Green rattle of the rushing water, river of nightfall urged on by windows’ lamplit glare to cascade before porticoes ramparts, holy silence of sleeping churches. The wind is a vendor belting curlicues of lustre, dancing through whispers, language’s wordy progeny, all held on a bridge beneath stars that weep and preen and feign indifference by a thousand turns as crowds look up, look down, unalarmed by twisting ambuscades of velvet night.

In many ways this poem is typical of the collection, even as it is a very particular manifestation. It depicts a scene where nature and culture interact. There is a pleasing roundedness to the expression (‘weep’, ‘preen’, ‘feign’) and it takes what might seem ordinary to the viewer and imbues it with a sort of importance. Yet it may fall a little flat in reaching for profundity, precisely because it resembles very good prose with line breaks rather than something with difficult and intriguing syntax, heady enjambment or any other form of engaging poetic technique. This is not to say it is unenjoyable, for there is great pleasure in reading it. Indeed, Trickster may be adept at what it is, but in what Robert Frost may have called its ‘thinkings’ it may be lacking for some readers.

At the level of content, Trickster exists in many countries but none of its borderlands. This work is about foreign places and cultures as intact; this is autonomy. Trickster, perhaps paradoxically given its name, is not so much about hybridity or the crossover of cultures that one sees in Mateer’s emptiness (say ‘The Drowning of Bahdar Shah’). This holds despite the appearance of ‘Japanese Tourists, Venice’. The title of the book is developed in the poem of the same name, which relates stories and myths about coyotes in North American Indigenous traditions. Undoubtedly, McCauley has offered this up in a spirit of homage and respect, but in telling it straight (in a manner akin to ‘Midnight on the Isola Tiburina’ and his voice throughout), there is the possibility of unknowingly repeating some of tropes and techniques that have been critiqued by post-colonialism.

Trickster has an essential quality as thought about, not thought through. Having said that, there are passages of genuine wit, and reading Trickster can be enjoyable and engaging. McCauley does have a skilful turn of phrase and a solid ear.

In Invisible Cities Italo Calvino writes of the relationship between Kublai Khan and Marco Polo, stating:

In the lives of emperors there is a moment which follows pride in the boundless extension of the territories we have conquered, and the melancholy and relief of know we shall soon give up any thought of knowing and understanding them. There is a sense of emptiness that comes over us at evening. (5)

There is a set of mixed feelings in reading Trickster – pride in our fellow traveller; a melancholy sense of the world’s beauty; relief that there is good work being written. But there is too, a sense of emptiness – that this may be all there is, that this is as good as it gets, which surely is not enough.