In the final stanza of Fitch’s opening poem, ‘After the Orgy’, we get a sense of some of the key themes encountered in Edwards’ collection:

Voodoo & u who peer at my cash my precious poor lark’ll hit the ceiling we’ll traverse toilets dissing the clock wise anti-delirium & go back Down Under where the rest sank Freud après the ludic deluge ici aussi totes

From the word, ‘Voodoo’, we are embroiled in the intrinsic and ritualistic modes of the book. Fitch’s Bloomin’ Notions is connotative of an effigy with which he invokes Rimbaud’s rebellious spirit and language, only to turn it upside down, hijack and re-verse. The movement of the above poem is vital to this effect: the vivid images (toilets dissing clocks), abruptness (‘where the rest sank Freud’) and construction on the page (oscillating back and forth in time with the ‘ludic deluge’) speak to the nature of Fitch’s Bloomin’ Notions; a real hybrid of ever-shifting parameters, implicated in free verse because this is the site of exchange and intersection. But this stanza does not pretend to be or do anything else; rather, Fitch spirals inwards, to the language of Rimbaud (go back), and resurfaces, ‘après the ludic deluge’, in circadian convulsions that mark the uncanny disposition of these poems as simultaneously old and new.

Take, for instance:

I is an / ugh it’s an ignoramus jamais jamais u say / or maybe nether nether Its inland sequel is counting on this Eur optic allusion to echo it &/ or braise it w/ outsourcery in terror pots of ennui & rain flowers overtly peer out no less ensorcelled than stoner food So naturally some cat

In this excerpt from ‘After the Orgy’, Fitch recognises his source material, abstracting Rimbaud’s ‘je est un autre [I is an other]’, only for the reference to be rapidly halted by a forward-slash. In this, Fitch perceives correspondence, preserving Rimbaud’s words, more or less, only to splay them out on the page, offering up the viscera of the original, before systematically dismembering and converting. In their place, Fitch creates a series of poems that suggest that the clean slate afforded in Rimbaud’s narrative, ‘After the Flood’, is no longer available. Rather, Bloomin’ Notions’ starting point is not the biblical flood, but the rapturous moments after climax. The seeds sewn in fertile ground are ejaculate, and what peers out is stagnant, circling around the loanword, ‘jamais’.

The French term oscillates between definitions of always and never, bound up in the referential past and subjective present of Fitch’s pastiche proclivity. Of course, in this paradox of the ‘mercurially deja’, one feels like Rimbaud’s mother after reading A Season of Hell: ‘What does it mean?’ The answer is varied, and fits succinctly into Rimbaud’s response: ‘It means what it says, literally and in every sense.’ In any event, Fitch expounds the imagined destruction of ‘After the Flood’ as necessary to create his ‘optic allusion [and illusion]’, and also as superfluous because the flood was mixed with sin and discharge.

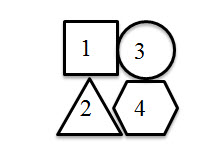

Still wet from the ludic deluge, we encounter Fitch’s ‘In Fancy’. In this poem, Fitch augments the homophonic qualities of Rimbaud’s ‘Enfance’ to ‘blow open the safe of childhood’, and drag us back to the past, before we drone forward into ‘car / nations either plastic or dead’. It is set out on the page like a child’s shape-sorting toy:

Fitch counterbalances the waves of metonymy and form equally, filtering down the shape-cum-stanzas to a fanciful discourse bent on creation, reflection, repetition and ambiguous destruction, in this order. As we move through the poem we encounter the construction of ‘red & / black monstro-cities’. Here Fitch leaves a breath that serves as a comma, his use of punctuation minimal and frugal, ‘clogging the way back’ (but to what exactly?), before reflecting on ‘a sea a terror a prayer’, timelessly attentive to ‘sonar clock bells’ that ‘has no ring to it’ and the ‘anvil of / a shadow colony w/ sluice gates’. I want to stress the ‘sluice gates’ in the concluding hexagonal stanza. That Fitch’s final shape should contain a conduit with which to hold back a body of water is at once a contrived mechanism, with which we attempt to forestall judgment (à la Badiou?) and a hallucinatory exercise into the deconstruction of society, whereby we will succumb to ‘either plastic or dead’.