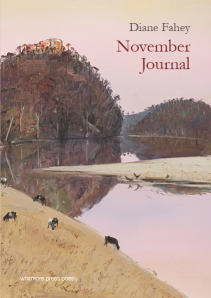

November Journal by Diane Fahey

Whitmore Publishing, 2017

Meteorites by Carmen Leigh Keates

Whitmore Publishing, 2017

The most recent work by Diane Fahey, November Journal, and Carmen Leigh Keates’ first collection, Meteorites, represent two offerings of quiet intensity controlled and mediated by distinct voices and their respective energies. These volumes, both published by Whitmore Press, comprise a young poet’s sequence brimming with restless, cinematically inspired content, in contrast with a more deliberately delineated work, using an ancient, stripped down discipline to let its luminous ideas and images more clearly emerge.

Fahey’s method is expressed in one of her hundred tanka poems with such clear and concise elegance it is worth citing ‘Day 11 / Research’ in full:

Fields, woodlands explored on foot. Shining-eyed fauna who’ll gaze, later from page, screen. Poems take shape, curved inside bellied drops of time.

The tanka form is over a thousand years old, and is typically used to convey a strong sense of connection to nature and the elements, while allowing for the self to express itself as part of these, with just enough space for personification. From the outset of her journal, Fahey encounters bright and almost beatific beings of the natural world, which by a sleight of hand, or pen, may also constitute ‘a treasure trove / to be sacked.’ Birds and insects come into view as crystalline entities, in the company of other animate phenomena that could well have arisen from a text such as Rimbaud’s Illuminations, recalling the hallucinatory wonder of unmediated contact in their apprehension and presentation. In her responses to Country (which is acknowledged with due respect and embodied in the book) Fahey takes careful measure of her wandering, and winds her lines through the leaves and light of late Spring days as they lengthen.

The phases of each day emerge with their living protagonists, animal life marking a sense of synaesthesia seeming to derive both from instinct and a palpable sense of Deep Image poetics. In the pre-dawn darkness, for instance: ‘Only the birds’ voices shine.’ Pipits, swallows, starlings and cormorants are just a few species which embody emotions ‘when you / enter the bird soul … felt and known as real.’ Addressing the wattlebird, Fahey asserts: ‘I know, wattlebird / we are one’, the bird and poet with their respective craft and materials, deriving lattice, mesh and text from the same original source, as ‘fingers splice and wreathe / vinous lines, language in leaf.’

This cross-species kinship is adumbrated by the presence of others, such as the snake world, unseen yet no less present in its semi-visibility, both an initial caution and ‘fugitive signature’ that marks her parting. By contrast, the solid forms of cattle stand as correlative for a slightly alien assertion or imposition on the landscape, but ‘As they graze, hide shifts over / rib cages shaped like small hulls’, implying transformative potential in the vessel-like structures mammals share and sometimes come to imagine in worlds beneath the skin.

On the surface, Keates appears to operate in an entirely different kind of landscape, one that has shifted onto screens, in liminalities and borderlands, and where: ‘If there are animals here / they have not yet been added. / Not even their voices.’ The poetry operates in spaces that are cleared, connected and preserved across time, yet punctuated by palpable absence or transposition. In a landscape of absent animalia there is also a shift in transportation: ‘Walking among the boat-graves, we must remind / the tree and stones of the fish before the fossils.’ This extends to construction. In an Estonian church, ‘The cathedral walls have stone fins like tendons. / Look what we are in.’ Even at the polarities of geographical location – Keates writes from the extremes of northern and southern settings – there appears to be no way of evading the multiple layers and dimensions of evolution.

Keates presents a number of these poems upon a backdrop of her own subconscious: ‘usually my dreams have a grey light’, and uses the intertextuality provided by images artfully recreated from cinematic masterpieces to eloquent, oneiric effect. A standout example is her take on Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev, with deft paraphrases of the pagan rites and raw power of youth, coupled with his novice monk’s sense of sexual transgression. The poem concludes with a pair of evocative images, before ending with what could be the book’s most memorable line:

On the surface of new knowledge his shame makes steam. The horses flush leather-black nostrils to test how far he’s gone. If you feel shame before a horse you are on fire.

Keates also indicates her imagist leanings and writerly role: ‘This poet is a photograph’, a special self-object, comprising silver dust, an animate artefact. This comes with a sense of Tarkovskian ‘Nostalghia’ in her final poem, applicable to the here and now as well as to the forces of history that create spaces between scenes that we remember, and others that are either forgotten or emerge from the strata of memory as discrete if uncontrollable events: ‘and in this layer, memory / is a demon that walks / like a soldier from a tunnel.’ This trope of return is far from being randomly placed, and in this alone, Meteorites finds grounds of affinity with Fahey’s ending which, ‘in its own time, in its own time’ is titled as an arrival and finds its metre in the footsteps of an echidna.

Keates’ endnotes tell us that the even the places seemingly unrelated to the cinematic strands that tie this book together are in fact significant in the history of film, as shooting locations or sites of residence for the auteurs themselves. They help form a palimpsest upon which presences from a recurrent past are reimagined and inscribed, just as Fahey’s living canvas collates eternally immanent forms of being in strands and sediment, capture and release.

Pingback: Review of Meteorites in Cordite | Poems about Tarkovsky films

Pingback: Meteorites Reviewed in Cordite | Poems about Tarkovsky films