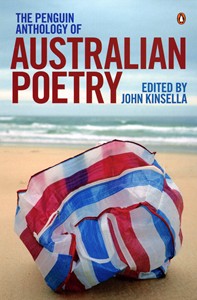

The Penguin Anthology of Australian Poetry edited by John Kinsella

The Penguin Anthology of Australian Poetry edited by John Kinsella

Penguin, 2009

Since the 1990s, academic discussions about literature have challenged, if not deconstructed, the project of a national canon. These discussions have centered on the notions of representation, inclusion, aesthetics, and importantly, identity. While the debates may at times seem atomising, the effects have invigorated literature, both in how it is conceptualised as a discipline and in how texts are produced. The late discussions about national literature give context to The Penguin Anthology of Australian Poetry, clearly a labor of love, edited by John Kinsella.

The historical anthology collects works spanning from the eighteenth century, including Aboriginal and settler poems, through today, ending with selected works by a post-postwar, young generation. In compiling the collection, Kinsella has tried to avoid popular notions and prescriptive expectations about Australian poetry, seeking instead to recognise works which reveal a tendency toward innovation and experimentation. The tendency, Kinsella finds, is pervasive in Australian poetry, present even in the earliest works. His approach has produced a historical collection, not necessarily an anti-canonical one, which pulses with life. Here are the songs of working men and women, the lyrics of established poets, the ballads of outlaws and convicts; here are the prose and verses of Aboriginal ancestors and contemporary indigenous poets; here are migrants inventing new idioms; here are voices from the margin and the center. The subject and style of the anthologised works, of course, vary greatly; but the sustained note is innovative.

Not surprisingly for a country of such regional diversity and breadth, a recurring theme in the poetry collection regards the land. To the first settlers, the landscape itself must have appeared like a vast experiment. This is reflected in pieces which express the poets' incredulity at the vegetation and animals. In 'Scraps from a Bushman's Note Book', an anonymous eighteenth century poet hails a “Land of many wonders” and proceeds to list a catalog of curious creatures, such as the black swan, emu, and platypus. A place of honor is accorded the kangaroo in works which similarly treat the speaker's astonishment, as in Barron Field's poem, 'The Kangaroo'. Field arrived in New South Wales in 1817, where he served as a judge. He addresses his muse as 'Thou Spirit of Australia' – indeed he anticipates how the world has viewed it ever since – and apotheosises the marsupial as kin to other fabulous creatures of the imagination, such as the Minotaur and mermaid. Poems such as these are reminiscent of the New World accounts of the Americas, whose observers similarly sought to describe an alien landscape. Kinsella, in his introduction, points out the ambivalence in most descriptions of the land by Australian colonial poets. As in the American case, the settler considers how such novelty might as equally favor the colony or swallow it whole.

While the views of early homesteaders and prefects express ambivalence toward the Australian landscape, another kind of settler seems much less conflicted. The poems and ballads of convict labourers are a fascinating inclusion in the anthology's selected works from the eighteenth and nineteenth century. The abjection endured by the men and women transported to Australia calls to this reviewer's mind, again, the American precedent of bonded and slave labour. To consider this “peculiar institution” is to better understand the founding of New World societies. Descriptions of the convict life are given by Frank the Poet, an Irishman who served regular time on a chain gang in New South Wales, and by Sarah Collins, who tells of a woman prisoner's fate in the penal settlement on Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania). “I was convicted by the laws,” writes Frank in 'Labouring with the Hoe':

Of England's hostile crown,

Conveyed across those swelling seas

In slavery's fetters bound.

For ever banished from that shore

Where love and friendship grow

That loss of freedom to deplore

And work the labouring hoe.

As with the contemporary Atlantic movement to end slavery, the resistance to convict transportation to the Australian colonies produced an eloquent appeal. Among the voices raised on behalf of the oppressed were those of Richard Whately, an Anglican archbishop and John Dunmore Lang, the first Presbyterian minister in Sydney, both anthologised in this volume. Likely because he opposed transportation, Whately exhibits no fascination with novelty. Rather he meant to move his reader to feel the despair of one exiled from home and family, marooned in a baffling land. But in the late great age of merchant mariners and whaling ships, when many young men sought to test themselves at sea, 'There is a Place in Distant Seas' might have had a different effect upon a reader. Because the listener wonders at the things he relates, Whately may unwittingly reproduce the allure of an untamed land. Indeed, free immigrants steadily followed after the convict ships, and prospectors for gold soon sought their treasure in 'Distant Seas':

There missiles to far distance sent

Come whizzing back from whence they went …

The north winds scorch, but when the breeze is

Full from the south, why then it freezes;

The sun when you to face him turn ye,

From right to left performs his journey.

The lines above are intended to illustrate the perversity, the literal backwardness of the place. Yet there is something here of a sea tale told by an old salt. The skillful handling of a boomerang, as described by Whately, has always fascinated people and generations have aspired to use one. The Australian geography and the seasons, in many minds of the North, are curiosities which hold exotic interest. This appeal did not simply begin in our own age of express global tourism. Interestingly, Whately himself never witnessed the things he described; he never traveled to the country.

There is no lack of works included in The Penguin Anthology of Australian Poetry which treat the Australian landscape as the focus of aesthetic esteem and national inspiration. Such poems are extant among the generations of settler, native-born, and indigenous people from whom the anthology draws. Included are works by Charles Harper, the nineteenth century poet born in New South Wales and considered the first non-indigenous, native-born Australian to take the local landscape as his primary subject. The ready engagement with nature presented in Harper's 'Flight of Wild Ducks' is echoed by Henry Kendell's 'Bell-birds', John Le Gay Brereton's 'Silver Gull', and by the worker-poet John Shaw Neilson in 'The Crane is My Neighbour'. The optimism of these works is also reflected in the urban portrayal 'Adelaide' by Fidelia Hill, who published the first bound book in Australia by a woman.

Perhaps few others have rendered the coextensive power and intimacy of the land as well as the Aboriginal poets Williams, Wullati, and David Unaipon, the latter poet said to be the first Australian of Aboriginal descent to publish a book. In tracing the subject of the landscape, Kinsella has also included works by so-called Jindyworobaks, authors who appropriated, some less intrusively than others, elements of Aboriginal culture to construct a poetics of non-indigenous, folk identity. The poems here by W. Flexmore Hudson, Ian Mudie, and Rex Ingamells, portray deep respect for the land and evoke the Aboriginal notion of dream time in connection to indigenous spaces. In fact, poems by non-indigenes and indigenes alike assert a native identity which is associated with the land. As Kinsella observes, however, “a celebration of the natural environment often goes hand in hand with a lament for the damaged and the lost”. The insight is borne by many twentieth century poets included in the anthology, for example by the Aboriginal poet Jack Davis, in 'Death of a Tree', who rather than a woodcutter's saw would have “a fitter end for such a forest giant / than this ignoble inevitability / because man was involved. / Man is pain”.

Poetic innovation – sometimes latent, according to Kinsella, in conventional work or expressed as radical content within conservative format and at other times apparent and openly transgressive – is the orienting principle of the anthology. This is evident in the later works collected here. Even, or perhaps especially, the conservative poetic territory of landscape presents an opportunity for exploration. For example, the contemporary poet, M.T.C. Cronin, speaks of 'The Flower, the Thing' in the spirit, if not the letter, of the linguistic existentialism of L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E Poetry. She employs the expressionistic image of a cut flower and contemplates the failure of language to ever tell meaning completely:

Don't be afraid of looking for the word which

will describe this perfectly for with the help

of the body the world will rise up, catch the wind,

and float to the clear surface of the waiting water.

Do you recall the world? Place your hand

on the place where it was cut from you and you

will know what pushes us to leave meaning.

Do we think, adrift, will we forget or be forgotten?

the flower answers that the mood has decided

its method of flying, its rest. The flower says,

I have believed enormously, have you?

The failure of language, she suggests, is the sense of displacement from the world and its contexts; yet though we feel its materiality, the world we mean eludes us. Cronin urges the reader to put her or his hand “on the place where it was cut from you and you.” The cut refers both to the stem of the flower, severed from the earth, and to the navel of the reader, where she or he was cut “adrift” from the mother, an encompassing, sensual world. The moment also suggests the theme of much Australian poetry, which expresses a longing for the motherland from which both early and contemporary immigrants derive. However the exile of which Cronin speaks does not refer to an imagined homeland, but rather to the sense of completeness which our language attempts, always inadequately, to restore.

It is exactly the work of poets, of course, to tell more than mere words can express. Exile is a kind of metaphor for a deeper alienation which art seeks to solace. This idea threads variously through the poems, for example, of Bruce Dawe ('Elegy for Drowned Children'); Antigone Kefala ('The Alien', 'The Wanderer'); Ouyang Yu ('Moon Over Melbourne'); Michael Brennan ('Flowers'); Paul Hetherington ('Skin'); Yahia Al-Samawy ('Variations on My Clay Heartstrings'); and Ali Alizadeh ('Rumi'). Each of these works suggests the notion of home as something less certain than a landscape, something which cannot be possessed with words. Alizadeh's 'Rumi', for example, tells of the mystic poet's flight across the open steppes, pursued by men who took offense at his verses. Behind, his city is lost and with it, hidebound conventions:

All knowledge, all art, and all history

drowned before my eyes. Freed

from the clutch of paperwords' ink dissolved in the lake.

I then drank. I was saved.

Rumi outruns the assailants who want to silence him. His victory is his ability to let go, transcend, to make anew. The tongue and the mind of the living poet preserve the word better than any page can fetishise, and he shows us. In such works as these mentioned above, one gets the sense of reply, given by modern Australian poets to their literary precedents who wondered what to make of a new world, and how to tell of it. One sees Kinsella's point about the Australian poetic inclination to experiment and innovate. If there is a national ethos which inhabits the poetry collection, perhaps it is this inclination. The will to innovate is woven through the many styles and moods of the anthology. Kinsella affords a view of a vibrant literature, one which tells the story of a land and a people who summon all the resources offered of mind and spirit to encounter it.

Perri Giovannucci holds a PhD from the University of Miami and teaches literature at The American University in Dubai. She is the author of Literature and Development in North Africa: The Modernizing Mission.