In the Photograph by Luke Beesley

In the Photograph by Luke Beesley

Giramondo Publishing, 2023

Time Machines by Caroline Williamson

Vagabond Press, 2023

We were all children once, but some of us more than others. In the Photograph (Giramondo Publishing, 2023) is Luke Beesley’s sixth book of poetry. Time Machines (Vagabond Press, 2023) is Caroline Williamson’s first collection. Children are central to both books. The speaker has a son in lots of Beesley’s poems, and Williamson’s has at least one kid present, too. The poets themselves were children once. To be a child is to be in a state of dependency that requires us to adopt a set of beliefs and desires that shape the course of our lives. These are our first myths. Myth provides us a type of psychic shelter from the pain of a life otherwise unorganised by interpretation. At some point our first myth breaks down and we lose the pleasure of its shelter. It is the pleasure of shelter that affords myth its positive associations. Myth recurs, we gain a new purchase on the world’s meaning. Between the loss of one myth and the emergence of the next there is a metaphysically arid interregnum that we endure for the sake of our dependents.

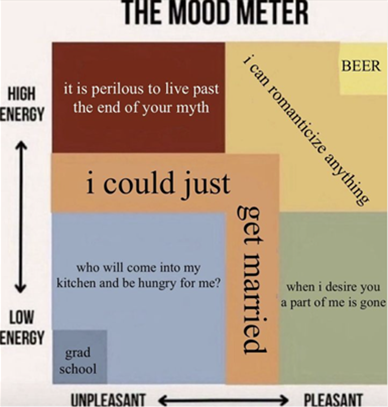

In the press materials for Red Doc>, Anne Carson writes “To live past the end of your myth is a perilous thing” (Madeleine LaRue, ‘Anne Carson’s Red Doc>’ in Music & Literature: A Humanities Journal, 2013). I encountered this ominous axiom by way of the below iteration of the Mood Meter meme graph. Its meaning returned to me as I thought about Luke Beesley’s and Caroline Williamson’s books. Both books speak to the pleasures and pains of particular myths and disenchantments. And to the virtue of endurance. Poems in both these books cover the “i could just get married” band but also some of the “i can romanticise anything” octagon. When they venture into the “when I desire you a part of me is gone” rectangle the object of desire extends beyond the romantic to include rivers, children, the reader, fictionality – the world as such.

In In the Photograph, the sites of activity of Beesley’s poems are as much the streets of Melbourne as they are dreams, daydreams, memories, and interiority: of the speaker, of other people, of art. It is surreal, intensely so, disorientingly so. Sometimes I liked this disorientation. When I’m locked into Beesley’s poems it’s because of the sensorium they generate. However, I didn’t warm to these poems as quickly as I remember doing with Beesley’s 2013 collection, New Works on Paper, when I read it in 2018. I recall sitting in the MCA café in Sydney, reading two poems about a jaguar and loving them. They felt playful in a way that was surprising and comforting. In the way that being involved in a simple but open-ended game is comforting: we are here, in this together, playing, witnessing one another’s play, committed to the game for now and its rules, and excited to see how we might transgress. The poems in that collection are, in my recollection, closely bound to the playful possibilities of the sentence. Puns, misdirections, and mischievous iterations. This sort of play is present in the new collection, but the longer poems of In the Photograph – two or three pages, as opposed to five to ten lines – offer space for other effects and games to emerge. Games of narrative, character, and voice. Sometimes the dual action of the playful sentence and the playful narrative was too much for me. Or it required me to read these poems closely, to be intentional in sticking with them. I would not read more than one or two at a time, otherwise the images, settings, and characters of each blended together, not always pleasingly. When I did pay them the right attention, I was rewarded with funny and sweet poems, full of careful consideration of the reality of suburban life in Australia, especially the quotidian life of artistically inclined suburbanite adults. The attention is intimate, the care is great. A tone of tenderness has grown more prominent in these new poems. Maybe longer poems were the venue required for it to blossom. This tenderness and the increasing vividness of the suburbs as the locus amoenus of Beesley’s poems are what I like most about this new book.

In ‘Time Piece’ Beesley writes of peak hour traffic as the “invisible momentum that took me back to a / very small fear of the day’s adult inevitability” and “on-rush: each in their not-so-much uncaring but distracted trajectories, en masse, racing forward […]And that dawning, really, in a child” (6-10). There’s melancholy in adult onrush, in adulthood as such. And in the loss of the myth of possibility as it is occluded by the dawning of the fact of inevitability – the fact that some things will be inevitable. There is much at stake here: childhood, actual children, style, composition, and friendship. The poem is spent giving an account of planning to meet with a friend, Daniel Read, for tennis and Daniel’s request for help with moving a boulder. The boulder is language, memory, therapy, life as such, and much else besides. We hear about Daniel’s history, problems, interests, and proclivities. Daniel and the speaker sit together for a while. The poem ends with the speaker thinking about the meaning of ‘we,’ observing a shift in feeling.

Read cried. Or I wondered if he shed a tear. it was a twist in emotional grammar—subtle anguish, real elegance, the sun turning—and I paraphrased hard, hearing him out. He knew none of this would add up [...] we finished our coffee and decided to move the rock before heading to tennis. (‘Time Piece’, 9)

This is a poem about friendship between men and the limited time available for writing, interpreting, and making life add up, all while trying to move ‘the rock’ and get some exercise in.

In ‘The Page Abandoned’ care continues as our speaker offers us an array of idiosyncratic and occultic new ways of finding their place in a book while reading (29-30). The first involves reading “to the top of every page after moaning softly against a squeaky bedhead” and:

a dream that spread out to engage the entire body, fingers twitching.

And that’s when I place the bookmark. Tuck it in snug and get

off the train one or two stops past my usual stop and walk an extra

100-200 metres each day, which would add up over the month and

year until I lost my job.

(29)

A dandiacal way to become unemployed. The poem continues, becoming patterned by the repeated figures of trains, train stations, Gerald Murnane’s A Million Windows, an unnamed female other who is in Murnane’s book, too. Throughout In the Photograph images recur within and across poems, engendering the feeling of a macro-sestina whose scale and scope we don’t ever fully catch sight of. The poem ends by clarifying the meaning of the moaning and the squeaky bedhead at the poem’s start: abandoning reading for sex, abandoning employment to read.

[...] yet we are almost done, and like most things printed, it ends up back in the bedroom. [...] She turns, we read on. Her back has a pressure point. We do a stop, we feel the weight. Feel it of an evening. We even joke about our 10 p.m. sex—the page abandoned. (30)

An image from ‘My Grandmother’ that has stayed with me is of the eponymous relation absolutely dominating the situation of a tram (46-48). Throwing things and bemused by the presence of her adult sons, she

[...] searched-out rucksack racks and found stacked and cracked dinner plates. She frisbeed them down the middle of the tram towards the driver. (47)

Here we see the limits of parental care. This is a late life rageful response to her sons’ expectant airs – cringe affects they continue to exhibit after she’s alighted without them:

the tram went by with her sons up against the windows, faces squished, arms out, gesturing her back. (47)

What would it be like to be confronted by three of your four adult sons waiting for you on a tram with a trestle table? It sounds a bit hellish. Like you’ll never get free from parenting. So, it makes sense to throw plates, throw a tantrum, or decide to faint. “But this was her swim” (47). The speaker reminds us of this as their grandmother is seen finding her feet and

[...] casually

giving the finger to a war veteran who had stepped off a chapel step

and dropped his cane. Smiling at him warmly.

(48)

It’s a dream logic, a good funny palaver of insoluble autonomy. Unassuming lines that, in their accretion, are totally excessive.

‘The Writer as Sand’ is a poem about childcare and how best to structure one’s morning routine (32-33). Events occur out of order. The speaker is awake and at their desk, and then again in bed trying not to wake their son, observing:

You’re in one room, for most of your life, going forward to your child and sitting over him. (33)

This is the ongoingness of childcare, art, and life. You have to keep writing and caring and working out how to start your day “wishing you / could keep the whole good word, its meaning intact” (33). The question of language’s wholeness isn’t at the core of Beesley’s book but the activity of caring for language and its users is. Beesley’s speaker is being a dad to the poems, caring for himself, caring for kids, caring for the poems. The poems are long because with kids caring has to keep going, lasting a week, a school term, until they’re 18 or 35. You have to continue appearing near them, and paying attention. You have to keep writing, keep caring. Caring might be your duty but hopefully also your happiness.