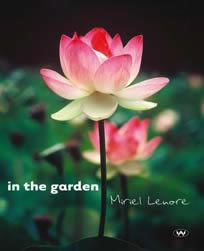

In the Garden by Miriel Lenore

In the Garden by Miriel Lenore

Wakefield Press, 2007

In response to the effects of global climate change, and probably informed by earlier exponents like natural historian Henry David Thoreau, Rachel Carson, Aldo Leopold, Eric Rolls and so on, the literary genre 'nature writing' has been re-invigorated and a new genre, 'ecopoetry', has emerged in the first decade of the twenty-first century. Miriel Lenore's sixth collection of poetry, In the Garden, reminds me of this, yet, whilst obviously aware of those strands in contemporary writing, it doesn't entirely fit the categories.

No fashionable flâneuse, in her previous books, Miriel Lenore has sought to imagine histories as she melds place and people using an extraordinary economy of language without losing feeling. In fact, the interrelatedness of mood and descriptive representation in her writing suggests traces of romance. Her deftly written poems, refreshingly unadorned by punctuation, combine perception and observation recorded at a slant, giving them a droll tinge. She quotes eclectically from writers as various as Rudyard Kipling, Eileen Myles, Andrew Marvell, Alice Walker, Nicholas Grimald, Emily Dickinson and others.

Here are forty-six short poems invoking the Adelaide Botanic Gardens – 'this garden I share with the city' – a refuge where Lenore can drift into reveries about original Persian walled gardens, ancient gods, goddesses, scientists, saints and artists. Where she can ponder strange questions like 'What are Molossian hounds?' – the gryphon-like mastiffs, copied from statues in the Vatican City in Rome, guarding a path that leads, with the accidental postmodernity of public-monument-kitsch, to an ironwork memorial to Elvis Presley.

This is a place that Lenore loves to be and loves to share. A friend's birthday is celebrated near an 'exuberant Hakea', a spirited symbol 'defying winter' as the friend turns 83 in this halcyon realm where they have 'shared a thermos' and many conversations 'surrounded by blossoms'. Wedding parties, Chinese students, English tourists, priests, lovers, patients from the nearby hospital, all frequent Lenore's Botanic Gardens.

Miriel Lenore has worked as a plant breeder which gives a definite clue to her interest in botanical science, one of the threads in these poems. She writes in homage to Carolus Linnaeus who invented a plant classification system and she revels in proper plant names – didierea, pachypodium, ferocactus horridus, platanus hybrida, quercus macrocarpa, cyperus papyrus.

There are references to the Museum of Economic Botany, the Schomburgk Pavilion, the Victorian palm glasshouse and other sections of this diverse Garden. The Museum of Economic Botany is a Heritage-listed late-nineteenth century building that yearns for classicism via the Greek style. Its contemporary annex is the Schomburgk Pavilion, named for an early director of the Gardens. Its purpose is cultural resources – exhibitions, cafe, souvenir shop and information. In 'Coco Indecent', for example:

In the Museum of Economic Botany

cases of polished wood hold

the Carpological Collection –Row after row of seeds and fruits

the small the gross the beautiful

in order of rank in their Kingdomthe tiny, not the immense,

will teach our groping eyes, the poet said

but my attention goes to bigThe bread palm like a pineapple

the sugar pine and jackfruit

the tree-sausage two feet longNo competition for largest –

the immense buttocks of coco de mer

double coconut of the Seychellesweighs eighteen kilos

Lodoiceae maldivica called Coco Indecent

yet heart-shaped says the labelThought to be aphrodisiac

keeping it from the king

cost hands or lifeA European ruler paid

forty thousand gold coins

for one nut –cure for poison and paralysis

more importantly

the Viagra of its day

The poems traverse many places following the histories of imported plant species but traces of Australian-ness surface often throughout the book in eucalypts, acacia (golden wattle), Mallee tree, auraucaria (bunya pines) and others, and the brilliant firewheel tree, the printmaker's icon:

This tree

says Margaret Preston

to me

but

doesn't know

that it's art

There is something very 'Adelaide' about the poem that describes a eucalyptus tree planted as a memorial to the inauguration of Australia's first Salvation Army in the late nineteenth century. And the pepper tree, significant in Lenore's poem by its absence from the Adelaide Gardens, is, for this reviewer, distinctly South Australian. I remember these big drooping, fine-leaved, pink-berried trees draped over petrified creek beds in the foothills of the Flinders Ranges, or shading a beer garden in Hackney in the unbearable, dry summer heat. The claret ash, in a poem called 'Adelaide's own', is a tree that originated, according to the poem, from a nursery mutation. Here, the description of the lower leaves is also 'South Australian' – the original Penfolds winery, Magill Estate, is located in the Adelaide region: '-the dun / colour of Penfolds Grange left / too long to drink'. The claret ash tree evokes a memory of Miriel's mother and the poem becomes elegiac:

I gave my mother a claret ash

when, in her fifties, unwillingly

she followed my father to his farm

carried water in buckets

to begin a gardenRare to find such subtle colour beside

the black box and Murray pine

of the Loddon floodplains

Thirty years after her death

the ash still decorates

the abandoned garden

and the heroic display in Botanic Park

gives her back to me

But overall, Lenore is writing about the times and places of origin of the components of the Botanic Gardens. The book's first poem – 'To make a botanic garden' – sets the scene where dedicated naturalists collect specimens against all odds:

Collectors persist –

heedless of dysentery

malaria, broken legs and death

cases of seeds and specimens

cross alps and oceans :

cannas from Turkey

peonies from Japan

cedars from Lebanon

Hawaiian hibiscus

proteas from Africa

Lenore is also wide awake in her awareness of Victoriana and colonial history. In 'Post-colonial', for example:

London plane trees

(Platanus hybrida, origin unknown)

wear delicate new leavesThe rhetorical oak

clumsy with years and surgery

stands centre stage

The poem continues and makes comparisons with London's Kensington Gardens but concludes:

Kensington's now arabia

while Australians born in Italy

and Vietnam picnic on this lawn

These poems depict an ideal park, a haven from the stresses of modern city life. However, there are occasional moments of disappointment like when the poet discovers that here the mythological golden apple is really a commonplace old quince and the poem, 'Aphrodite's golden apple' ends with an unexpected and atypical moral remark/chastisement about the lack of discipline in contemporary Dionysians. 'The garden of good & evil' warns of the darker properties of plants coexisting with healing qualities:

the Judas tree is also called

the Love treePoisons abound

alongside remedies

deadly nightshade beside

the cure for colic

This review only offers impressions of the expansive reach of this collection. There are many more turns and facets of the Gardens to discover here – a herb circle, the Sappho rhodendron, a poem remembering Adelaide's connection with Alfred, Lord Tennyson, the rose garden, waterlilies, fuschia, the amazing rice grain, a lovely description of an arbutus tree, the first tree – the mezoic gingko, palm trees and so on, and a relative of papyrus in 'Sacred Papyrus':

but a rush of flowers celebrate this air

and the umbrella plant another Cyperus

twirls like a showground plastic toy

Apparently two poems in In the Garden are written by guests, Andy Goldsworthy and Sergio Redegalli, a name that, given the absence of explanation for including these guest-poems, suggests a pseudonym to me.

A close-up photo of an intensely hot-pink lotus flower on the front cover, handwritten titles and quotes, detailed photos denoting each section of poems mean that this small book has been packaged, deceptively, in great-gift-idea mode. But as you read the poems you discover that it is not that at all. The poems are smart, perceptive, wittier than the package suggests, and if the book is available in the Schomburgk Pavilion shop, I'd suppose that many unsuspecting Adelaide Botanic Gardens visitors might find themselves converting to poetry after reading this engaging memento.