Yimbama by Ken Canning/Burraga Gutya

Vagabond Press, 2015

‘Oppressors always expect the oppressed to extend to them the understanding so lacking in themselves.’ – Audre Lorde

Reading a book by an Indigenous Australian author comes with a certain mythos attached. There is an uncritical expectation of explanation, of being taken by the hand and taught profound lessons that are appropriable, then displayed as trophies to liven up ‘Western’ society. Because indigeneity is often imagined as oppositional to modernity – and because modernity is assumed to belong to the ‘West’ – it’s as if the reader is sneaking off and doing something a little naughty, a little rebellious, by peeking over the fence at the fascinating and magical world of the ‘ethnic’ writer. And there is a reward for this, be it gratitude from the authors for deigning to listen, or kudos from one’s own cohort for being so very brave and ‘open minded’.

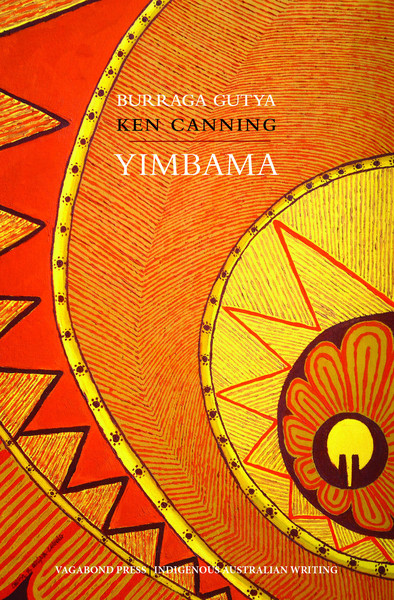

At first glance, Yimbama promises just such an experience. The cover, with its shades of red and yellow, the two names – one English, one Language – the title itself, and the words ‘Indigenous Australian Writing’ at the bottom, all set up the expectation of discovery. The glossary at the back of the book seems to confirm this – Yimbama means ‘“to understand” in the Bidjara language,’ it says. The back cover reveals that Ken Canning/Burraga Gutya learned to read and write in prison, and for the last 40 years has been a poet, playwright and Indigenous activist, all of which dovetails beautifully with the expectation of inspiration and bravery.

So we read.

And, with any luck, we actually listen.

Yimbama begins with ‘Name Game’ the last line of which is ‘But you can never call me yours.’ With this Canning defines himself and educates the reader regarding who he is and how his aboriginality interacts with the white occupation of his country. This is amplified in the next poem, ‘Visibility Zero’:

I don’t belong to this concrete chaos. When your guns could no longer kill, your historians you know your programmed robots, wrote me out of social view. Beware you devils. I am Black and I know how to de-program.

The use of words like ‘devils’, here and elsewhere, is obviously loaded, but in the context of the white colonisation of Australia, it makes Canning’s position unequivocal.

This relationship with and rejection of colonisation is taken up even more explicitly in ‘Painless’ (p24):

I am over 220 years of colonial oppression of racial hatred, brutality, death and land theft has been my life. I am every Aboriginal person in this country now called australia.

These poems are blunt. They seethe with righteous anger. There is no embellishment or understatement for the sake of aesthetics – Canning says what he means plainly. This may make the prosody somewhat simple in places, but it communicates a visceral anger that more delicate verse would not.

The colonisers of his land are not alone in Canning’s firing line. He also addresses ‘The Traitors’ (p40) who, although they come ‘from a culture/as old as time’ have allied themselves with white Australians or ‘the boat people of 1788’.

You have lost your place with us, the proud Aboriginal Peoples of this ancient Land. You the traitor, have been rolled in the white man’s flour and baked into his perfection of how he wants you.

The image of milled white flour – European import to Australia – reinforces the ‘traitors’ tainted status although what exactly constitutes traitorous behaviour is not named.

There are also two poems that stand out for their use of Aboriginal English. ‘Old Clever Woman’ (p30) and ‘Tree Talk’ (p70) are a delight, particularly in the context of this collection. In the same way that other post-colonial writers bend and break English to make it fit colonised landscapes, Canning uses Aboriginal English to interrupt the flow of ‘Standard’ Australian English and tell a story not in the coloniser’s voice but in his own. Aboriginal English constitutes the flip side of colonisation – in interacting with a new land, the language too has changed in distinct ways – adaptation is a necessary condition of settling, after all. In the act of colonising, the coloniser too must change.

The use of Aboriginal English also helps the non-Indigenous reader understand that they are experiencing a foreign reality and centres the Aboriginal voice more strongly than protests in standard Australian English. My only criticism is that there are not enough of these poems. Quite aside from the politics of language use, they have a rhythm and music that is more expansive than many of the poems. Even though the old lady is suspicious of the tourists, and even though their clicking cameras remind her of guns and a massacre, this is not an angry poem.

This old one need no picture mind say like yesterday all same click – click – click – click, the guns shoot fire, little ones screaming, scream never go away. Pink faces make same no talk noises. The old one got one big photo, killin’ times her mob dyin’ click – click alla same.

Instead, it is a defiant poem imbued with stability and staying power. This is not the often fetishised, gracefully suffering native in need of saving. This old lady isn’t budging. She is watching and judging, and she will not give ground. This is a poem of protest and of dignity that cannot surrender.

Towards the end of Yimbama, the poems start to sound hopeful, although they remain fierce. Canning seems to be moving towards reconciliation, although ‘Reflect,’ ‘Solidarity,’ and ‘Sharing’ do not advocate capitulation or even forgiveness. Instead they give the reader space and a path towards understanding.

In a tender poem titled ‘My Children’ (p82) Canning considers telling his children of what awaits them. Instead, he chooses to let them play just a little longer, for he knows ‘the horror/of truth’ is inevitable. Most minoritised people will relate to this, but the desire to remain happy and comfortable is also what produces the most strident resistance to acknowledging the horror that one’s own people have inflicted on others. Yimbama challenges readers to confront this truth, to listen to Canning’s protest and his rightful anger, and to understand their own place and role in the disenfranchisement of Indigenous Australians. Without this understanding, there can be no genuine reconciliation.