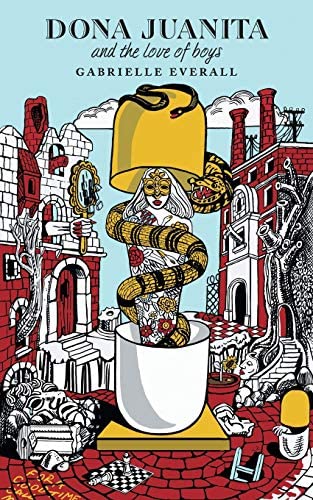

Dona Juanita and the Love of Boys by Gabrielle Everall

Dona Juanita and the Love of Boys by Gabrielle Everall

Buon-Cattivi Press, 2020

In the ‘Reflection from the author’ at the beginning of Dona Juanita and the Love of Boys (Buon Cativi Press, 2020), Gabrielle Everall states: ‘The main struggle of the novella is about the protagonist’s love of boys. Some of the poems are written about two guys I had crushes on’, as well as, ‘there is lesbian erotica … as my best sexual experience was with a woman.’ This introduction, frank and fun and almost ditzy, unsettles what might be taken as quite a serious book. Performing ‘honesty’, it downplays the somewhat hysterical introduction written by John Kinsella who, ‘feel[s] this is one of the most important poetic narratives to have appeared in English anywhere, at any time.’ It draws attention to the presence of the author, the banal reality of the author’s body and personal feeling. Put simply, Everall ‘love[s]’ Dona Juanita. So do I.

Its ‘importance’ is not what I am interested in. I am drawn to the energy of the work whose noise drowns out ‘themes’ at times, and at times brings ‘themes’ to the fore by performing, for example, psychic pain in contemporary Australia so dramatically. But it’s the performance of the thing … the performance ‘gets in the way’ and you, the reader or audience, are drunk on it, spinning. We might also note, ‘a postmodern Werthergirl [one of the author’s avatars] rarely cries’ – Dona Juanita as a postmodern epic is more playful and less tearful than some readers might expect it to be, given the often disturbing subject matter. As a book ‘about’ female desire, it is generous and open; it is so much more than its aboutness.

At a reading at the Dancing Dog in Footscray (recorded for 3CR and available as a podcast), Gabrielle Everall hits the phonemes hard. Her opening poem, which appears in Dona Juanita, booms: ‘INDI ROCK GOD’. She has a deep Cruella De Vil voice. Listening to the recording, it makes me laugh involuntarily. Out of fear? It is a terribly desirous poem, seductively performing ‘the catch twenty-two / of suffering that causes jouissance / and a jouissance that causes suffering’. The female speaker watches the man, whom parts of her ‘become’, who she chews up and spits out, for whom she performs both publicly and privately, invoking Rilke, Jesus, St Theresa, self-harm, S&M and ‘pigs in mud’. All for the speaker’s ‘him’ (soon to be re-invoked as ‘Rock Tosser’), but the poem at the end of the day is ‘for’ Everall herself. You sense her pleasure in making it, this damaging joyous object. It’s filthy, hectic work, and when brought to life in performance is even more extreme.

Gabrielle Everall is an indie rock god of a kind; she has that mystique or ‘presence’, and an IDGAF attitude that comes through clearly in certain strange fragments at the end of poems:

eyes like bloody chocolate and sometimes like pale tetras you lean against the photocopier

What is that? There’s some nod to the ‘imaging’ of men in the photocopier (an important theme, you might say), but the poem is way shiftier than any clever hook it might have (‘tetras’? Little fish). Everall pushes her poems very hard as she thinks through the love of these boys. As well as sick endings (the most rattling: ‘It’s just nothing and rape’), the poems in Dona Juanita have extreme openers, which feel high risk and give a sense of her aesthetic: ‘Bliss me out’; ‘Penetrate me with your flag’; ‘I fantasise ‘bout him’; ‘Ploughed by the discourses’, and so on.

The poems are at their best when they offer strangeness. It’s a careful strangeness, I think, and one which doesn’t care to explain itself. The poems are very crafted. Everall is a poet who exercises power over words; the desire she feels may be the driver of this control over language (when she can’t control the ‘real’ man?). The phrases, often short, come out smooth like bricklaying, so serious and bold that again they make you laugh despite the gravity – ‘that night / when I watch / Go Fish on television / I can’t identify as a lesbian / ’cos the taste of this blade / is still in my mouth’ – like when someone sits on your chest in the right spot. And while the shortness of her sentences and breath betray anxiety or tightness, Everall works within that constraint to produce frightening phrases like ‘I was raped / in a Nick Cave t-shirt’ that land calmly on the page but vibrate, more bricks piling on the chest. I also want to note that Everall really halts at a full stop, and there are a lot of full stops in Dona Juanita. You can hear it best in live performance: where the breath ends, it ends hard, heavily. The last word in an Everall sentence is like a giant piece of blu tack, holding up a glossy Greco-Roman face, ‘debas[ing] him’.

Dona Juanita is also enjoyable as auto-fiction. It offers a better ride than prose – the proliferation of memoir-ish books we ‘love to see’ – by moving so much more licentiously. Instead of reflection, we get a density of feelings presented as discrete sentences, each like ‘passion fruit [cracked open] with her mouth’. It’s as if the feelings are simultaneous and the poet is stuck with sentences as the form for presenting or producing said feelings. But why sentences, which seem to dominate this book among some fragments, when poetry doesn’t demand it? I think it’s the talky quality of Everall, whose performances make the most of the short sentence, not pithy but spitty, angry yeah but more like evil, in a fun, sexy, almost-joking (-is-she-joking?) way. A little bit ‘If I had a gun I’d shoot the man’ (Gig Ryan), but not the man who was sexist. Rather, the man whose ‘eyes were Adonis blue’, who just was. Perfect because he is the crush. Of course, we as readers know that Adymson and Lot, whom Everall’s speakers lust over, are just … some dudes (later, on the other side of crushing, it’s confirmed: ‘Adymson’s a dud’). But the poems, especially early in the piece, are about the ride.