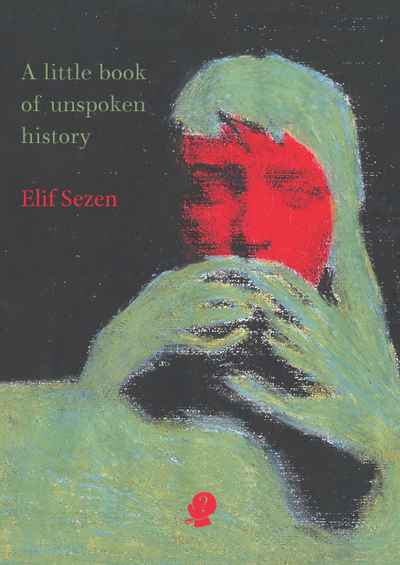

A little book of unspoken history by Elif Sezen

A little book of unspoken history by Elif Sezen

Puncher & Wattmann, 2018

Where do footsteps lead, these frustrated blind hunters

In these times many of us from all corners of the globe have more than one place we call home. Concepts of nationality, attachment to place, a sudden annunciation of enlightened belonging or steadfast refusal of it can be dissociative, painful and conversely full of artistic promise. The very notion of home may be welcome or fraught with regret. It may involve mixed emotions or at worst, trauma.

Elif Sezen, a Turkish-Australian multidisciplinary artist currently living in Melbourne, has developed a sophisticated methodology to work across media and to explore these themes. By foregrounding a personal inner life within the rigours of artistic and spiritual practice, she eschews narcissism through a focus on the transformative image. As a poet, translator, and as an artist Sezen has access to a world of imagery which appears to float in an imagined but deliberately structured dimension. Through deft selection, her practice of writing does not overwork its own tropes, which centre on childhood, trauma, displacement, the politics of migration and the metaphysical ambiguities integral to journeys real and imagined. Sezen’s images of trauma carry with them an apparent resonance, tantalisingly suggesting an overcoming, but also simultaneously suggesting the indelible trace of that trauma.

An example of this effect can be seen in the epigram ‘Slap of the morning’:

Slammed doors are still being heard Who are they?

Coming after two poems focusing on childhood, ‘On the topic of first parents’ and ‘Childhood’, the poem resonates as a deep early memory suggesting violence with the sonorous slap and slammed, and fear through the final line Who are they?. The poem, employing Sezen’s regular trope, the door, appears to echo through space in a similar way to a masterly haiku.

Speaking generally of her artistic practice, Sezen has written: ‘I suggest the continual expansion of a poetic persona as a methodology of surrendering to the infinite’. Her poetry renounces the world’s ability to deliver infinity; instead its imagery emerges in devotional splendour or in political anger at the cruelties inflicted on refugees, especially those in long term detention.

When I first encountered Sezen’s work several years ago, I was attracted by what I saw as the European texture of the work, with its philosophical emphasis and often-romantic interiority. This connection has been astutely observed by Nadia Niaz, in a review in this publication of Sezen’s first English collection Universal Mother. Niaz focuses on the influence of Rilke (and importantly, his use of Sufi imagery), but also stresses Sezen’s access to diverse traditions, including Ottoman and Persian poetics, and to modern protagonists such as Forugh Farrokhzad. Several poems in A little book of unspoken history are dedicated to what can be seen as a constellation of artists, images of whom form something of an interior gallery, a feature many of us share, functioning as icons of our very existence. Sezen’s gallery includes Holderlin, Kahlo, Camille Claudel, and significantly in ‘Our celestial doorway’, a moving tribute to Farrokhzad:

Let’s meet up in your imaginary Esfahan in a city where women glow in green, head to toe when we bend down from the Khaju bridge, our reflections on the water turn into non-poisonous ivies, a city of secret sovereignty where bombs won’t explode

A significant poem included in A little book of unspoken history is ‘Chronic Fatigue Syndrome’. The open, sequenced structure of the poem allows the key state of the suffering of the body to move effortlessly through themes of spiritual renunciation, the trauma of non-belonging and the vicissitudes of migration doubly effected and politicised. In an artist talk at her recent exhibition The Second Homecoming at Counihan Gallery, Sezen mentioned how moving back and forth between Izmir and Melbourne had left her without a sense of home. In this poem, fatigue enforces a focus back upon the self. In 1. Awareness, Sezen writes:

Now that I am tired I must open up inwardly, like a lotus blossom yes, I must open my paper-like lids towards the benign feature of absence for I will encounter her, in the very bottom: that archetypal mystic, resembling my mother by her glance perforating the silvered smoke my small self will pass away because I am tired because fatigue is a lovely trap made to save my body from its old cage I get rid of the worldly clock losing beguiling sleep

This sequence leads to a surge of empathy, where like an ascetic removed from the fray, the poet releases the possibility of benevolent compassion:

become a voluntary mute so I can speak for them They surrender their souls wrapped with flesh and blood and breath back to where they came from

As the poem continues, it develops a floating sense, the pinning of an elusive image, the transformative power of angels, and the devastating liberation of surrendering to pain:

La Minor impatience

Do black humour

CRESCENDO the pain

Is so glorious here