Milk Teeth by Rae White

Milk Teeth by Rae White

University of Queensland Press, 2018

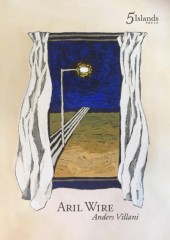

Aril Wire by Anders Villani

Five Islands Press, 2018

Poetry debuts are not necessarily juvenilia. The vagaries of poetry publishing mean that by the time a poet’s first collection is published they often are, at least by some standards, emerging fully formed, able and ready to demonstrate their skill to a willing audience.

By the time a poet has amassed a book’s-worth of work and managed to secure a publisher, it’s a fair assumption that they have found their voice. This isn’t to say that their voice won’t develop and change as they continue to write, but that a debut poet is by no means an inexperienced or untested one.

The debut collections of Brisbane-based Rae White and Melbourne-based Anders Villani are the work of people with honed and confident voices. These are poets with extant careers whose books are a celebration of the culmination of their work to date.

White’s debut collection Milk Teeth was the winner of the 2017 Thomas Shapcott Poetry Prize and published in 2018 by the University of Queensland Press. It was also shortlisted for the Victorian Premier’s Literary Award in 2019, whose judges described it as ‘challeng(ing) pre-existing categories: gender, interior and exterior landscapes, the way we assume language is fixed.’ Milk Teeth is an energetic collection, equal parts experimental and traditional, in which formal and structural innovations lie comfortably alongside poignant and personal observations. White is equally at home disrupting an otherwise familiar scenario with fairy-tale elements as they are with anchoring the reality of unreal scenes with finely crafted detail.

‘Mother’s Milk’, the first poem in the collection, ably demonstrates White’s capacity as a lyric poet while also showcasing their taste for disruption. In this poem the ordinariness and intimacy of a mother showing her daughter’s partner a box of saved baby teeth is expanded upon and heightened into a visceral body-horror exploration of the desire to possess and encompass a lover:

I swallow feel it scrape & chafe lodge in my throat. That night, its crystal teratoma grows

White’s lyrical facility is also proven by ‘Skyward’, depicting an intimate encounter between partners. It zeroes in on the patterns of light cast onto one person’s bare belly through a canopy of leaves:

I trace each teardrop spectre with fingers then tongue

Sitting alongside lyric qualities that demonstrate White’s facility with language and image are more experimental works that challenge both poetic convention and readers’ expectations. White has enlisted a number of other-than-poetic forms into their poetic service, including Twitter posts, programming code and bureaucratic language. These poems use their mimetic forms to highlight the social structures and frameworks that are used to declare, confirm or erase identity.

At times White’s counter-use of such languages and forms to convey political messages occasionally threatens to destabilise those forms to the point of neutralising their menace. The point of these exercises, however, is consistent and clear. One of the most powerful examples of this re-weaponised language is ‘Regarding your Suspension’, a parody of the implicit biases baked into bureaucratic processes. The poem simmers with weary but still-sharp sarcasm:

‘Dear Rae Your gender has been flagged and suspended by our team, due to being one or more of the following …’

In addition to these poems calling structural biases into question, other poems in Milk Teeth challenge another almost invisible preconception: that of the physical orientation of poems on the page. Many of the poems in Milk Teeth are set at 90 degrees to the usual orientation of a book, requiring the reader to turn the book sideways in order to read them.

While this design decision may simply be a result of White desiring a longer line for these poems, and while it may be connected to the common poetic experience of being published on a screen before ever being published on a page, it’s hard not to think of this particular challenge to convention as being of a piece with the challenges to bias and preconception that White puts forward in other aspects of their work.

White’s challenges to poetic structure and style are in keeping with the way their poems’ subject matter also challenges conservative views of gender. With poems like ‘Microaggressions’ and the award-winning ‘what even r u’, White centres the personal experience of insult and aggression, both passive and active, regularly experienced by non-binary people.

But while gender identity is at the fore of some poems, White also challenges the potential assumption that a non-binary activist poet can or should only write about their activism. This point is successfully made by poems like ‘Plants my exes gave me’ and ‘Enraptured’, which depict experiences like gardening and falling in love that are common to all humans. In doing so White validates and celebrates the continuum of gender with other modes of experience, and hopefully educates those who believe they can only experience non-binary life vicariously.

There’s an appealing messiness, a futz and clutter, a chaos to the world White writes. It’s a world of ‘Biscuit grit in / bed Enoki mushrooms / woven with pubic hair’. There’s tenderness here too, portrayed by a deft hand that pens memorable, shy and gentle love scenes that share space with the boldness and confidence of experimentation and political assertion. Milk Teeth is an eclectic mixtape of a book, a stellar debut exhibiting equal parts ‘fuck that noise’ and a visceral love of life.