Cartoon Snow by Aidan Coleman

Garron Publishing, 2015

South Australian poet Aidan Coleman’s previous book of poetry, Asymmetry, was published in 2012. It charts Coleman’s traumatic experience of a stroke, and the resulting loss of symmetry in his body, life and writing. The book strings together revelations made startling through poetic bluntness, from the initial shock of incapacitation to the excruciation of gradual rehabilitation. However, physical damage was not Coleman’s main worry, but rather loss of language. He conveyed his anxiety in an interview: ‘a poem relies on metaphor … if you don’t get that real high … you’ll never write a poem’. Happily, these fears were alleviated with Asymmetry, which not only teems with astonishing and idiosyncratic figures of speech, but also operates as an entreaty for readers to think about illness anew.

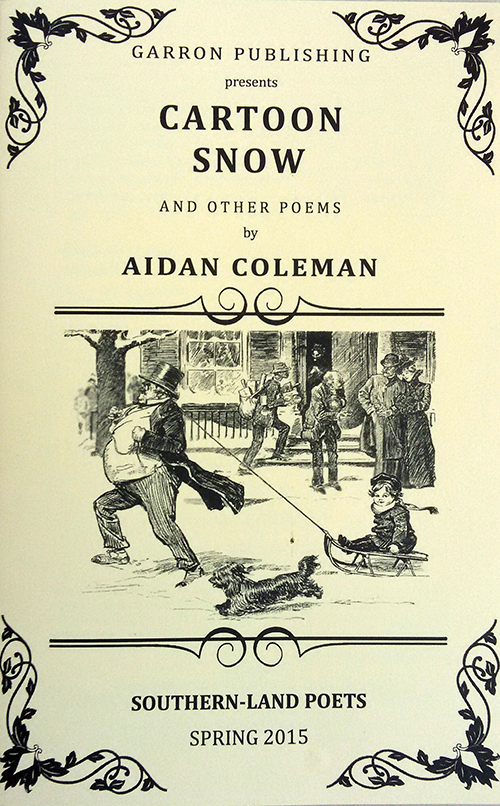

Published three years later, Cartoon Snow demonstrates Coleman’s enduring acuity. The 17-poem chapbook is thematically lighter than Asymmetry, but it does not lack in an underlying philosophical enquiry. The cover features ‘The Spirit of The Time’, Charles Gibson’s 1910 whimsical illustration depicting a joyful child being pulled along on a sleigh by an equally joyful relative. Windows are coated with heavy snow but there is no indication of malcontent. Cartoon snow, evidently, appears different to factual snow. The sharper edges of reality are softened by the gentle pixellation of a romantic, pictorial focus rendering the subject innocuous. The cover is apt for a collection that asks questions about simulacra.

The book opens with the titular poem ‘Cartoon Snow’, where the speaker observes a freezer packed with ice that is difficult to dislodge. Coleman writes: ‘You realise the benefits of cartoon snow’, drawing the reader’s attention to the notion that literary illusion often softens the blow of existence, the freezer a signifier for life’s hardships. The poem instantiates this act of softening but also offers a reflexive vision on how these metaphors are produced. They are as ironic as they are romantic: ‘Sugar cubes of igloo bricks … / dazzling acres, you would dress for’. Such lines juxtapose a contradiction between what we know to be true, and what we wish to be true. It is unlikely you would actually have a desire to dress for the necessary realities of a very snowy day.

‘Cartoon Snow’ sets the tone for the upcoming pages, as we are pulled into a shared, tacit knowledge of how poetry works upon us. The paradox in romantic irony is at play as the poem drifts into the phantasmagoria of the ‘snowy night’ of Anglo-American poetic tradition. The drift brings to mind such antiques as Robert Frost’s ‘Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening’ and Emily Dickinson’s ‘Snow Flakes’, operating within a snow-globe of ethereal, exquisite phrases. The phrases engender marvel and lift us up above the mundane, yet they can also trap us in a frozen, false perception of safety. Coleman’s poem offers similar repose from the actualities beyond – such as a snowy night that is bitterly cold and painful to trudge through:

How gently it erases fox-prints and sleigh-tracks, the stamp of hoof

The speaker expresses dyadic desire: for poems to convey brilliant verisimilitude, but also for a heightened version of our world. We are in want of cartoon snow because such representations ease ‘the vexatious sharp edges of our pasts’. It offers a respite from relentless facts and rationalism. The speaker admits that it is tempting and pleasurable to ‘retire/once more to the puffing cottage, its windows a blazing/ marmalade’. The huskies inside are peaceful as they ‘settle for the uncluttered life’, an admission that brings the poem full circle in its contrast to the early image of the cluttered fridge. Poetic illusion is a kind of truth, Coleman seems to say, and it occupies the edges of the corporeal to ease our lives as we graze against them.

‘Sideshow’ is Coleman’s playful exploration of an Australian Christmas, in which he writes of a ‘Christmas down by the river’ where the carols are distinctly Australian, in a location that cannot achieve the illusion of a wintry and cosy European Christmas: ‘ice-cream van carols/pour into evening’. Such European notions are irrelevant in Australia’s heat and among its plethora of unique native animals. Coleman points out ‘kangaroos instead of reindeer’, and the unintended blasphemy of the nativity display where ‘an echidna, a wombat, and a platypus’ brings the baby Jesus his gifts. This deliberate hybridisation operates through comic images, but the evident delight in this feels radical. Coleman displays his uncanny wit in the last stanza, as a sudden vagary reveals his fondness for it all:

Is it the joy of their delirium that makes it look so much like looting? Anyway, we liked it .

Such examinations continue in ‘Barbarian Studies’, which takes the everyday scene of supervising a child and deploys it to break down the illusion of stereotypical masculinity. Here, masculinity is stripped from the male parent and comically endowed to his child. The parent imagines himself carrying out a more ‘manly’ activity elsewhere, which could be singing drunkenly like ‘a coachman circa 1840’, or in a Viking boat rowing hard. The poem surprises as it illuminates the title’s significance: when one thinks of barbarian, one usually thinks of someone who dominates through aggression. But is that not an apt description of many children loose in a playground? Certainly, they invade and conquer such areas. However, and this is the hinge on which the poem pivots, they still need their parents to propel them and assist their navigation. They may behave like Vikings, but as Coleman grudgingly remarks: ‘the Vikings … at least did their own rowing’.

The concluding poem ‘Diagram and Leaf’ is a fitting, meditative moment among the comical metaphors and metaphysical questions. It addresses more directly the longing for truth in the semblances of poetry. After the disruption of poetic liberties, Coleman reveals an admiration for the ‘willing suspension of disbelief’ – as Coleridge famously called it in 1817 – employed by readers to truly appreciate the poem’s interpretation of the world. Coleman admits to ‘tricks on paper’, but such tricks and illusions are celebrated in ‘Diagram and Leaf’. The water ‘sparkles’ – it is not grey and dull, and we arrive at who we are by asking why we value this. What lies beneath ‘obsidian and mirror’ is not how we are, but how we long to be – the world remade through our submersions in poetry. Coleman has not lost his touch for singular metaphors. As he deconstructs the role of such metaphors in this exceptional chapbook, these poems invite us to question our perceptions of reality, heightening our understanding of what we often need the world to be, even if only as ‘tricks on paper’.