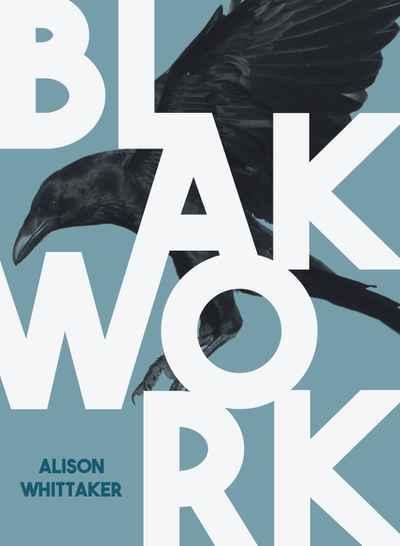

Blakwork by Alison Whittaker

Blakwork by Alison Whittaker

Magabala Books, 2018

My sister and I devoured Blakwork. She’s nine and I’m not sure if she understood most of what Alison Whittaker talks about in this collection, but it resonated with her. With both of us. Whether that was our shared identity as women, as Aboriginal women, or something more, I’m not entirely sure. In Blakwork, Whittaker combines her career as a lawyer and her craft as a poet to peel back colonialism until it’s left exposed, raw, bleeding in the hands of the very people whom it has subjugated. She examines Indigenous work and labour, a physical theme manifested in a collection that embodies that exact physicality through form, structure, and rhythm. From her commentary on the subjugation of black bodies to the way the poems sit on the page, the reader is constantly thinking and moving with the collection.

Jumping from poetry to prose to memoir, Blakwork comes together, eagles out, then comes together again. It makes you turn your head and the book, it has you reciting lines aloud to feel the way they hang in your mouth. The reader is constantly working for the words on the page, so it’s difficult to get comfortable when reading this collection—but that’s the point. Too long has the comfort of a colonial readership within been valued within the Australian literary scene. Like that shadowy place in The Lion King, Blakwork situates the reader in a place of unrest – a place that has been pushed to the outskirts of history, shrouded in darkness. From the first, titular poem in the collection, Whittaker outlines her poetic thesis through commentary on the physical oppression and indentured work of Aboriginal people and the emotional work colonial Australia still expects us to do, including being tasked with the responsibility of reaching reconciliation and with being an emotional leaning post for people seeking to alleviate their white guilt.

The theme of indentured service is particularly significant in ‘many girls white linen’, which co-won the 2016 Judith Wright Poetry Prize. This poem discusses the physical labour of Aboriginal women by reimagining the missing girls from Joan Lindsay’s novel, Picnic at Hanging Rock. The reference to Australia’s literary past, however, is a throwaway, almost as if the scripts were flipped and, in this alternate history, it is the white women, rather than their black counterparts, who are not deemed significant enough to be mentioned. A more explicit reference to Australia’s colonial literary culture is the poem, ‘a love like Dorothea’s’. From the rhythm of each line to the fresh twist on Dorothea Mackellar’s famous phrases, this poem speaks back to Mackellar’s ‘My Country’. While Mackellar wrote ‘I love a sunburnt country’, Whittaker hits back with ‘I loved a sunburnt country’ (my emphasis). This subtle but powerful shift from present to past tense echoes the trauma the land now known as Australia has endured, the trauma the First Peoples of this land continue to endure, including the loss of land, culture and connection:

I loved a sunburnt country—won’t it please come back to me? Won’t it show me why my spirit wanders but is never free? I will soothe its burns with lotion, I will peel off its dead skin. If it can tell me why I’m drifting ever further from my kin.

In both ‘many girls white linen’ and ‘a love like Dorothea’s’, Whittaker rewrites a colonial history all Australians have grown up with and offers a counterview of which most people are ignorant. This strategy is seen in a series of poems scattered throughout the collection, each one constructed using forty-nine most common three-word phrases of well-known court cases. A lawyer by training, Whittaker uses the law as well as acknowledging its misuse and colonial nature. A poem about the Mado decision, ‘the skeleton of the common law’, is full of phrases referencing colonial structures and names. In particular, references to ‘the Crown’ are in almost every stanza, lingering, giving the poem a heavy weight. Similarly, ‘exhibit tab’ looks at the death of Ms Dhu in a detached, clinical way. The removed ways these poems consider the displacement and death of Indigenous people only serves to highlight the rigid, colonial nature of the Australian legal system and the historical way leading figures in this country have and continue to talk about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people so that our voices are muffled or all-together obscured.