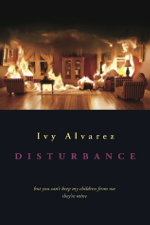

Disturbance by Ivy Alvarez

Seren Books, 2013

re-membering by Janet Galbraith

Walleah Press, 2013

How do we truly belong here on this continent, come to terms with our collective and personal history and build a genuine home for the future? And what of the ongoing legacy of violence on an intimate scale, by men against their partners and children – how can this be challenged and interrupted, changed into mutual trust? These are crucial questions; complicated and painful, yet unavoidable. Two new books recognise this and respond with what, to me, are poetry’s great strengths: the generation of an empathic interpersonal encounter, and that aching paradoxical space of both knowledge and productive ignorance.

Disturbance is Ivy Alvarez’s second collection of poetry. Its dedication to Dorothy Porter, Ai and Gwen Harwood is not at all surprising given that, Alvarez’s poems are comparably unflinching, unsettling and precise, exposing the horrors of family violence with an artistry that is always in the service of its compassion. Furthering the link with Porter’s work, it is also a verse novel, but a relatively unconventional one. Rather than following a linear progression, Disturbance throws us immediately into atrocity and its aftermath – the murder of a mother and a son by the father, who takes his own life, leaving a daughter alive. Each poem that follows is a fragment, retrospective and prospective, accumulating a picture of what we want to know but feel disturbed to approach – how did this happen?

When I began reading it, I assumed that the story at the heart of the book was fictional, a composite of many cases synthesised from research. Subsequently, I began to wonder how ‘real’ the poems were; in a way, attempting to measure the gap between poem and reality, I was reaching for the real, yearning for it. But Alvarez notes that Disturbance is ‘an imaginative retelling of and a response to actual events’. Like an exhibition of documentary photography, it presents framed yet incomplete impressions from particular perspectives, which confront us with the existence of the real while acknowledging the gap between an account and its source.

The book is both kaleidoscopic and choral. We are presented with the thoughts and memories of the mother, Jane; the police officers, in their enculturated impotence; the journalists, with their condensations and abstraction; and the son and daughter, with their confusion, bravery and cornered-ness. While the poet’s own aesthetic temperament gives them a certain consistency, each of these character voices is distinct and convincing. The grammar, vocabulary, emotional tone, punctuation and lineation, are all finely attuned to reflect their individual posture and energy. Yet the music of the poems is subtle and unobtrusive; Alvarez doesn’t want anything to overshadow what is being exposed and examined. Sentences are generally complete and naturalistic, a fusion of the mundane and the metaphoric, of the composed and the chaotic, which is quietly chilling:

My dinner rests warm in my belly. I’ve just come in for my shift. Familiar smell of old coffee, stale sweat accumulates, hovers near the ceiling. … ‘What is the nature of your emergency?’ Weariness wears my voice. But then she speaks. I type quickly. I press buttons. ‘What is your address?’ The pads of my fingers prickle, become slick. Keys slip beneath my skin. (‘Operator’)

Appropriately, there are also occasions where the language itself breaks down or fragments. Here, the poetry draws on an almost risky knowingness and wit, but it never loses its focus and visceral impact, as in ‘The Detective Inspector II’, which begins ‘ – eyes make/in/cre/mental/adjustments/in the dark’. Or, in ‘Hannah’s Statement’, where the breath catches and is held in white space:

once after my brother ran he placed my hand on his heart

Alvarez’s language is most chaotic and unmoored when we hear from Tony, the father, whose ‘own hands must do something’. His confusion and possessiveness seem fuelled by a profound detachment – of his self from his body and from others. If there is any summary of his motivation to be found, Alvarez provides it negatively, as Tony states: ‘there is no explanation for me’; ‘Real things seem untouchable to me’; ‘I pass for someone ordinary/someone who looks like me’ (‘Tony’). Near the end of the book, we spend quite some time in his mind, which is populated by familiar and archetypal metaphors of ‘red’, ‘hunting’ and ‘dark’, yet also with surreal and unexpected images, such as ‘dust that skims/across your eyeballs’, ‘the subdermal itch’, ‘rank/bin juice’, and an account of the aerodynamics of golf balls. These bring us closer to a kind of visceral intimacy, rather than understanding.

The one poem which I am still ambivalent about is ‘See Jane Run’. Here, the central murderous event of the book is depicted through the truncated sentences and simple language of the iconic children’s characters, Dick and Jane. While only two-thirds of a page and in short paragraphs, this prose-poem seems to be Alvarez’s way of conveying, through parody, the unconveyable horror. It’s an undeniably affecting poem, but one that I am not drawn to read again.

By contrast, ‘Disturbance’ compellingly revolves around a black hole at its core – the mundanity of evil and the seeming inevitability of violence. And the short poem that opens the book, ‘Inquest’ signals silence as a response to inexplicability:

Members of the family wept as the coroner read out her pleas for help. Nothing softened as they cried. The wood in the room stayed hard and square. The windows clear. The stenographer impassive. The spider under the bench intent on its fly.

I say ‘seeming inevitability’, because while there is an echo of a kind of ‘natural’ hunter and prey in the poem’s chilling conclusion, and while the wood stays ‘hard/and square’, the reader is constantly drawn into a state of empathy and resistance. These events, condensed into black text with such articulate and meticulous white space around them, are given to us in all their horror as artefacts, made things, which can conceivably be unmade. It is Alvarez’s great talent to frustrate us, to refuse to provide easy explanations. The only possible response is outside the book.