Love in the place of rats by Paul Hardacre

Love in the place of rats by Paul Hardacre

transit lounge, 2007

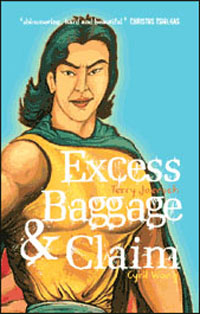

Excess Baggage and Claim by Terry Jaensch and Cyril Wong

transit lounge, 2007

Although Love in the place of rats and Excess Baggage and Claim – both published by the independent Melbournian press transit lounge – arrived in the mail together, it was the disquieting title of Paul Hardacre's second poetry collection that grabbed me first. I immediately flicked to read his bio on the last page and found out that he is a prolific thirty-something publisher (managing editor of papertiger media) dividing his life between Chiang Mai and Brisbane. He has spent time (rather than having 'travelled') in Myanmar, Singapore, Pakistan, Hong Kong SAR, Indonesia, China, New Zealand, Ireland, the Netherlands, the United States, Italy, India, Cambodia, Vietnam, Laos PDR, and Malaysia.

For two weeks now I've been carrying his slight, handsome collection graced with a single photograph (by Sam Shmith) of a dark, windy sky on the front and the storm lifting with hope on the back cover. I read it on foot and trams. While walking I seem to constantly get lost on each page, and the same happens to me on trams. But when I stop moving and sit in a caf?©, I throw out my bookmark; because Love in the place of rats begins on every page, on every line. Open it where you please; and there is no end to its fragments jotted down, ideas in capsules carefully savoured, created with a chisel, recorded with a paintbrush.

The ocean rolls, whispers and returns, right through the avoided commas and full-stops; brackets that are opened but rarely closed, backslashes cut and add / add / add. It exhausts me. Time and experience are molten into liquid and, like the question of love, the answers are in the sand scooped up and poured through our hands. In 'Poem in 5', for example:

in her bifocals what does it all mean

she asks a range of objects shoe lingam

typewriter people (attesting the advantages

of civil service) farmers stick collectors

headmen mendicant children the raj or its shadow

undefined mourners & here the value of a good driver

The collection is dedicated to 'she-of-one-hundred-&-eight-names', and she is all over it. Who is she? Time, movement, or indeed simply the poet's girlfriend? At the end of my journey through Love in the place of rats, I decide to read the acknowledgements purely to find extra clues, and I learn that 'place of rats' is apparently the indigenous name for those suburbs surrounded by the Brisbane River just south of the CBD – South Brisbane, West End, Highgate Hill, Hill End, Dutton Park and parts of Woolloongabba. I'm not so happy about finding a literal reference for the title so easily, having its mystique destroyed so quickly. But it's a great title all the same. People hate rats; and love is, well, often far away from the comforts its fulfilment promises.

Hardacre's objects of desire are obviously manifold, and Love in the place of rats references all the places he has spent time in, as well as the company he has kept in the work of Joseph Conrad, Jack Kerouac, Phillip K. Dick, The Opium Clerk, Tricky, Cindy Lauper and Arthur Schopenhauer. Graham Greene also joins the list, and his quote from The Quiet American I find most revealing: 'Rooms don't change, ornaments stand where you place them: only the heart decays.' When you travel to so many destinations, where are you going? Do you ever leave, or just carry your home around with you? Hardacre provides an answer of sorts in 'Boiler':

richard undoes my head speaking

chekhov or dostoyevsky & somebody's

father was a gambler in a caravan park

at hasting's point & closer to pottsville

words give way to sand blown so hard &

southerly it stings the legs of juvenile poets

& this all happens near a causeway or a bridge

so romantic it rains at the first sign of reality &

words return at low tide only five letters

heart stapled a steady diet of stained thought

Travel promises love fulfilled through experience itself; whilst spending time in a place suggests a deeper engagement, and commitment. It is this conflict that makes Hardacre's unwieldy Love in the place of rats such a rich result that demands to be read and re-read. One will ultimately find escape inside oneself, if that's what one is escaping from.

In contrast, Excess Baggage and Claim by Melbournian Terry Jaensch and Singaporean Cyril Wong is much more matter-of-fact. Again, the authors appear to be two thirty-somethings trying to make sense of what matters the most: love. One of the voices is an Australian tourist, the other a Singaporean local. Both are gay men. Their words sing to the world, melting the gulf between Singapore and Australia into one universal exploration of love and lust.

This much I discover from reading the back cover blurb and the endorsements. I launch into the first part – 'Excess Baggage' – and find Jaensch, as the Australian tourist, contemplating during his flight to Singapore:

Had I but the right cutlery, I could cut it

but in this age of convenience and terror I

am not to be trusted.

He asks before landing: Is the act of exploring love through poetry as useless as this plastic cutlery? Once on the ground Jaensch doesn't disguise any fear of the unknown, whether in the matters of love or being in an alien place. In 'Leaf the Size of My Torso', Jaensch writes: 'What can be accomplished now? Better, I had attempted something erotic or biblical or cheap, or to have simply named it, from the outset love – thoughtlessly.' Then in 'I Am Listening To-': '#3 The colour of my skin shouting – quietly down Kerbau Rd.' and '#13 Last night's curry – dealing with my shit alone.'

Jaensch's brutally honest words make me immediately warm to his persona that is reminiscent of Christos Tsiolkas's. In fact, Tsiolkas's own endorsement of Excess Baggage and Claim adorns the front cover of the book: 'shimmering, hard and beautiful'. Not unlike Tsiolkas's protagonist in the novel Dead Europe, Jaensch's tourist arrives on strange shores feeling out of place, clammy, over-compensating the attempt to take it all in his stride. He makes the reader wonder if it matters where one is from, or where one is going, when one is in the familiar company of oneself.

In 'Excess Baggage', Jaensch frequently contemplates such questions – and, of course, love – through songs and in karaoke booths: love in a booth, love as karaoke – it seems so simple, obvious, and predestined until the speaker actually picks up the microphone. To shout or to stammer? To sing or to whine? The concluding lines of the poem 'Placebo Effect' throw all caution to the wind:

This is

and is not the bridge, the frets. Is and is not

the moment. Hell, anyone can strike a chord –

this is a spasm, an accident that has and has

not waited to happen. A forgetfulness on the

part of our driver: let's not take for a truth, for

a lucid moment – a wind or caution thrown to.

Jaensch strikes one hell of chord, as he is not complacent. 'There is such a thing as too much comfort!' he writes in the poem 'Haw Par Villa', quoting from a father who claims that with comfort comes eternal gratification. But Jaensch believes that love is not static, but rather an ever evolving entity, even if it is with the one person.

Cyril Wong starts each poem in 'Claim' – the second section of this collection – with a fragment of a conversation between lovers, and then writes a response or continuation. The first line of this conversational fragment is then also the title of the poem. Some quotes feel like tousling with a lover's hair; others reek of rejection, confront – and thus set up each poem. In 'Are you comfortable talking about this?':

'Are you comfortable talking about this?'

'Yes, not a problem.'Back home from the beat,

I thought about the man

who had stood me up. I saw

his face at that first meeting.He sat down beside me

at the bar, alone. He was

the first to say hi, and even

offered to buy me a drink.

'I only knew about this place

a month ago. I wasn'tout to anyone, even myself.

Whilst Jaensch is constantly asking the reader something, Wong ends up answering himself by beginning with the question of the quote and then delivering an answer through the rest of the poem. But Jaensch's words are more self-centred, internalized, whilst Wong's poems read like short stories, or succinct first person scenarios. The directness of the language ensures that the reader can't sidestep the most confrontational scenarios that recur in Wong's collection of poems, especially the looming figure of a sexually abusive father. Wong both tells us and lets us feel his own escape mechanism through Singaporean pop culture's mix of Bollywood, Almodovar films and Ming dynasty period dramas. In 'Are You On Tonight?', for example, he takes us on stage to feel what it's like to perform in front of an audience of your own good and evil ghosts. In 'Turn Around.' Wong is stuck in the deepest blues, and contemplates a life of not being able to 'sing all of my dwindling days' due to throat cancer.

The constant presence of sickly sweet pop music in both Jaensch and Wong's work ties this collection into one, but what makes it a compelling collaboration whilst retaining two individual voices, is the two author's referencing of each other's poems. At times they are subtly intermeshed leaving you wondering if they are talking about each other – only to find out that they're not. But when in one poem Wong says 'I went to a Karaoke pub once and did it with an Australian in one of the rooms', I find myself rereading Jaensch's karaoke adventures, and, whilst looking for references, I discover new meaning in his poems. I then go back to Wong and feel the same thing happening again.

This endless exchange – between the two poets' philosophising and sharing their experience in love; between what is and what isn't love; between being Singaporean and being an Australian abroad; between memories conscious and subconscious – is what makes Excess Baggage and Claim as enduring as the pop music referenced in the poem, and the conversations we have to this soundtrack; as our lives go on, with memories evolving, and we lose and find ourselves in love.

Moses Iten is a Melbourne-based freelance writer, DJ, radio host, editor and curator.