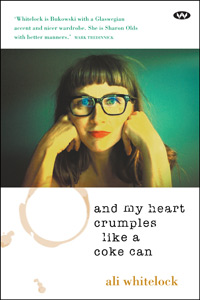

and my heart crumples like a coke can by Ali Whitelock

and my heart crumples like a coke can by Ali Whitelock

Wakefield Press, 2018

Despite the sorrow of its title, and my heart crumples like a coke can will have an utterly expansive effect on the reader’s beat-box. My little heart almost burst as I read through this collection for the first time. And then the second. Like some classic 90s rom-com – or was it drama? – that you watched and then re-watched every weekend on VCR as a teen, Ali Whitelock’s book seems to encourage a closeness, invites the reader to experience a genuine connection with the poet/protagonist and with their bevvy of sidekicks, both the heroes and the villains. I find myself genuinely touched by the liquid, visceral rawness, the careful simplicity and confessional glory of Whitelock’s poems.

Perhaps it has something to do with the seemingly breezy style; I picture Whitelock scribbling these poems in five minutes – maybe ten – on the underside of napkins in a crowded café somewhere on Glebe Point Road, the Bukowskian edginess of it all just floating off her fingers to bless everything it touches like butter grease. This, I thought as I read, is precisely the poetry I would like to write. This, I thought, is the poetry I should be writing. Why am I not writing this bloody poetry? I thought, these odes to the horrid heat and shopping centre scourge of of the suburbs, the aging body, vaginas, chicko rolls and the farts of the dying? I am awestruck when confronted with such passages as this one, from ‘what you must you do/ you must keep your mouth shut’:

if you want you can tape it shut with the snoring tape – he keeps it on the side of his bed. Sometimes it rolls off onto the carpet the cat hair sticks to it because what you must understand is how you feel is not how others feel. The important thing you must do is not say how you feel if you say how you feel he will roll his eyes and sometimes after the eye rolling there will be a sigh and what that means is you must not say that thing again. Eventually you will get to know the things that make the eyes roll and the chest sigh and you will stop saying them. If you hold a hermit crab shell to your ear you can hear a rushing and this rushing is the sound of everything and the sound of nothing

This excerpt – and I would have included the whole poem if there was room for it – reveals Whitelock’s singular flair. The emotive content is moving without falling into sentiment, the motif and metaphor clever without leaning towards the pretentious. Even the centred structure works to jolt the reader into the importance of the particulars. This familiarity – imperative yet as casual as a conversation with a bestie – is I believe, is the kind of tone we all aim for, while endlessly editing and re-editing that seemingly unavoidable bullshit out. Her no-holds-barred, uncensored honesty when it comes to the small things – snoring tape, choice of lipstick when you turn fifty, brand of cooking chocolate – and the terrifyingly large things – death, exile (both voluntary and forced), aging, the mid-life affair, the aftermath of the affair – is so powerful it is contagious. Here are a few lines from ‘your friend said it was a love poem’:

the therapist had seen it all before – a thousand times apparently – in women my age with no children go on then rub it in at least i’d had the presence of mind to ask about diseases you said you had none backed it up with a printout of your latest blood results you kept in a folder marked ‘bloods’ which I didn’t find strange.

This blunt conversational tone is echoed, with perhaps even more harrowing honesty, in this excerpt, from the stand-out poem, ‘water’s for fish’:

as cliché as it sounds i always imagined i’d get the call in the middle of the night the one that would announce that you were dead or at the very least be dying i’d be bleary eyed would thank the caller and hang up grateful that i am safe my seventeen thousand kilometres away and geographically exempt from delivering your eulogy from shaking hands with those i have no wish to shake hands with

These excerpts also highlight the less cohesive aspects of the collection, which are the slightly discombobulating lineation choices, and collisions of atypical sentence structures. Quite often, the poems appear as performance texts adjusted for the page; sometimes fully punctuated and precise, and sometimes – part emphasis, part rebellion, I’d imagine – utterly not. While Whitelock’s lineation most often works to build emphasis, at other times it can start to feel a little heavy-handed, especially when the powerful and poignant word choice is more than capable of speaking for itself and perhaps needs no further emphasis. That said, anyone who has read the Beats, perhaps especially Bukowski (who is clearly, wonderfully, a strong influence on the collection), will have little or no problem navigating the momentary bumps caused by unpunctuated sentence collisions. Certainly, when listening to these poems read aloud (in a smoking hot Scottish accent; Whitelock is an impressive reader), any thought about formatting fades away.