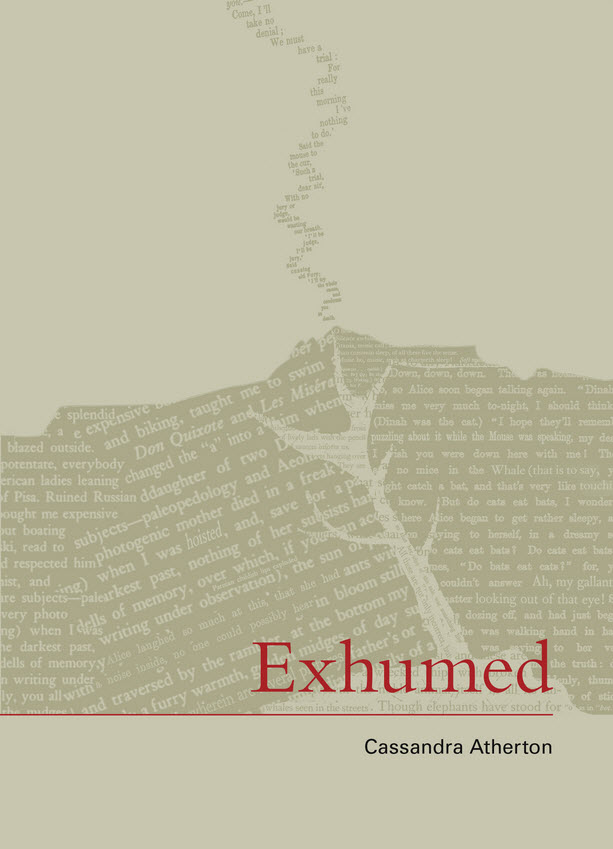

Exhumed by Cassandra Atherton

Grand Parade Poets, 2015

Dazzling, vibrant and terribly witty, Cassandra Atherton’s Exhumed does not give itself over entirely to the horribly serious, gruesome images invoked by its title. Nor of course does it travel down to the desperate depths of its epigraph’s hero, Rosetti, who (in)famously ‘recovered’ the book of poems he had buried with his wife. Yet Atherton’s collection of prose poems is nonetheless morbidly fascinating and even darkly exhilarating, with some of the more raw, emotionally-fierce poems evoking similar queasy feelings in the twenty-first century reader, perhaps, as the nineteenth-century poet might have experienced recovering writings from the grave of a loved one. For loved ones haunt the pages of Exhumed in abundance, with all their conceits and betrayals on display, coupled seamlessly with high literature or popular TV, colour or sound, texture, taste and scent. These are embodied, visceral poems, alive with sticky sex, sugary gastronomy, grandiose and not so grandiose imbibing: ‘no gripe water. Maybe absinthe’ (‘Seed’ 22).

Picking up Exhumed, I confess I was daunted. Perhaps I was in a bad mood, perhaps glancing over the great chunks of text with their pages of intertext endnotes felt a little like facing the suggested reading list for an end of semester essay. This collection felt heavy, both in word length and subject matter. And yet within moments, the opening poem, ‘Bonds,’ sucked me in and under, even with its thirteen references in the back pages:

There can be no valedictions here./ So now our lives are cotton. And although cotton breathes, it is also the/sarcophagus of our relationship. Embalmed memories. But I promise to/ dig you up. Like Heathcliff. Or Rossetti. I promise to unbind you and gather you in my arms (11).

Exhumed contains a romantic, Romantic quest: to ‘write the space between / my heart and my pen’ (‘A Room of One’s Own’ 28) or perhaps to uncover what was lost (often before it becomes lost): ‘I worry every day that you will go to ‘Empty Trash’ and / I will disappear.’ (‘Rubbish’ 49). The quest of the reader, then, is to follow along, to become lost deep inside the narrative (and then of course endeavour to dig themselves back out). For this book of prose poems unfolds a love story, with its everyday ins and outs: ‘I want a red Smeg 473L fridge. I want my whole kitchen/ to be red. He draws the line at a red fridge.’ (‘Plum(b)’ 12), moments of exhilarated hope: ‘I belong / in Massachusetts twirling myself in his sheets. Rotation. Revolution. / Spinning ginny. Ginnie to his Riddell’ (‘Anonymous’ 15) and boldly confessed fears of the imminent end: ‘But you have never bought me flowers. / Or shown up unexpectedly. And you won’t stay for a lifetime. Because / neither of us has a lifetime left to spend. Together. Or apart.’ (‘Tsundoku, Neon Love’ 74). There is no small amount of sorrow at the inevitability of imperfection in relationship here, coupled with a maudlin yearning for perfection nonetheless; all cleverly drawn out with the grand device of allusion. A supermarket notebook in ‘More’ becomes a motif for all that cannot be gained: ‘You want to buy/ all the green notebooks at $1.99 each but know they will replenish the / stock when you leave. You can never have them all. Somewhere, someone / else will be using one of your green notebooks’ (34). Yet, in ‘Chigger’ there is still joy in what can be experienced, what may be grasped, albeit momentarily: ‘I fell in love with fireflies in Pennsylvania. / I remember trying to take photos of their luminous green abdomens as / they took of and landed in the long grass’ (60).

Exhumed contains far too much viscera to dissect in such a short review. For all their sparkling intelligence and playful satire, these poems, I believe, are profoundly embodied and emotive. There is a glorious layering here, and the themes flow on from each other through the interring process to the necessary disinterring to create what is an (albeit diverse) narrative whole. The ‘glue’ (‘Bonds’ 11) of childhood food such as a ‘McDonald’s Happy Meal’ (‘Alice’ 41) sticks literature giants like Nabokov (‘Lolita’ 23) to the ‘Hello Kitty love hotel’ (‘Shinjuku Morning’ 74) with seemingly little effort.

While there are some actual belly laughs to be had throughout, the vast blocks of text (and endless intertexts) do not make for easy reading. Sometimes it is difficult to determine who or what is hiding whom: does the sarcasm reveal a vast emotional void or does the almost gruesome body imagery and heavy reliance upon others serve to place a shield over what is perhaps a raw and unknowable human response to upheaval? Everything slightly mentioned on this expansive ground seems to open the way to something else entirely, and heaven forefend we should arrive at a conclusion concerning the speaker here, the quixotic voice is only too ready to set us off on yet another bisecting or bifurcating path. Perhaps, though, this obfuscation hardly matters, the pikes of prose alone are enough to ward off the queasy reader and the robust reader will devour it all, with vigour and a large dose of ‘Apple Pie Moonshine’ (‘Seed’ 22).