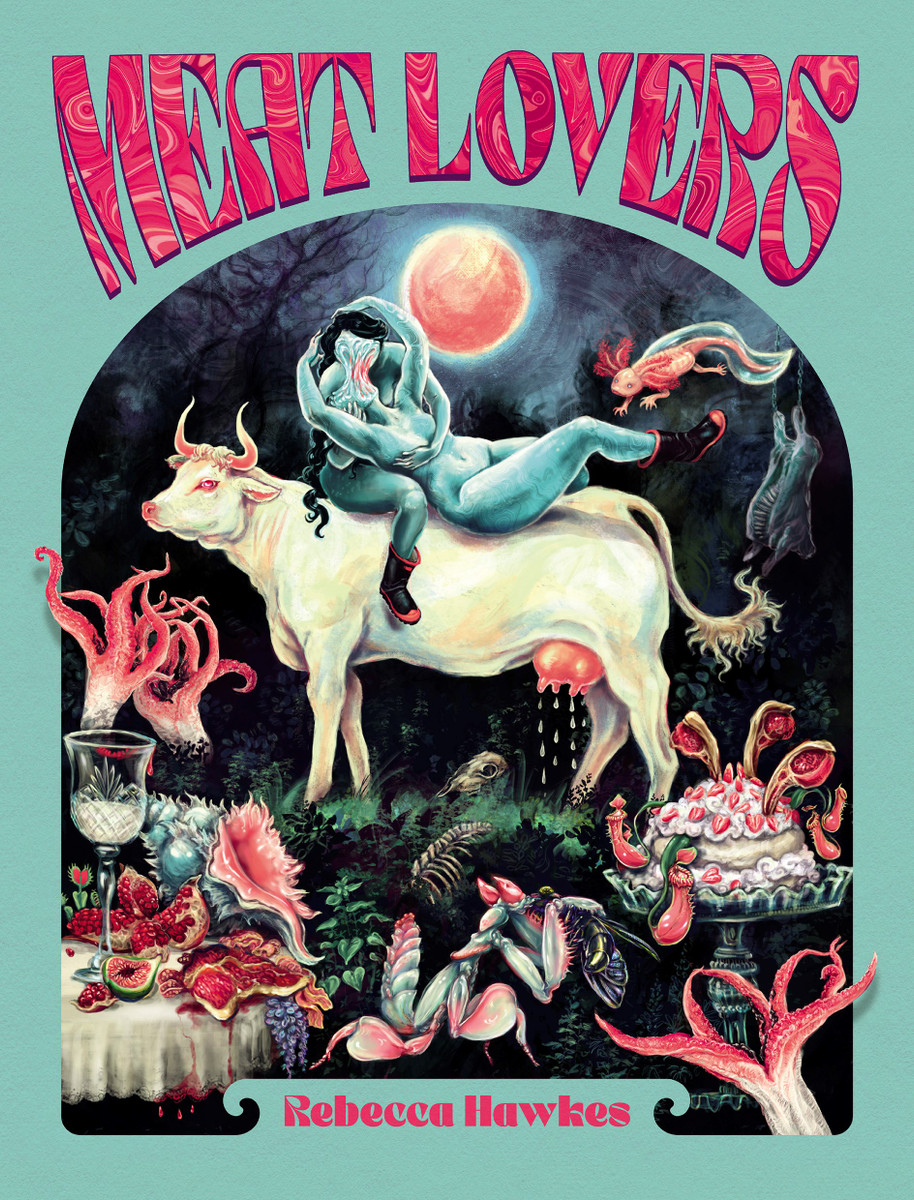

Meat Lovers by Rebecca Hawkes

Meat Lovers by Rebecca Hawkes

Auckland University Press, 2022

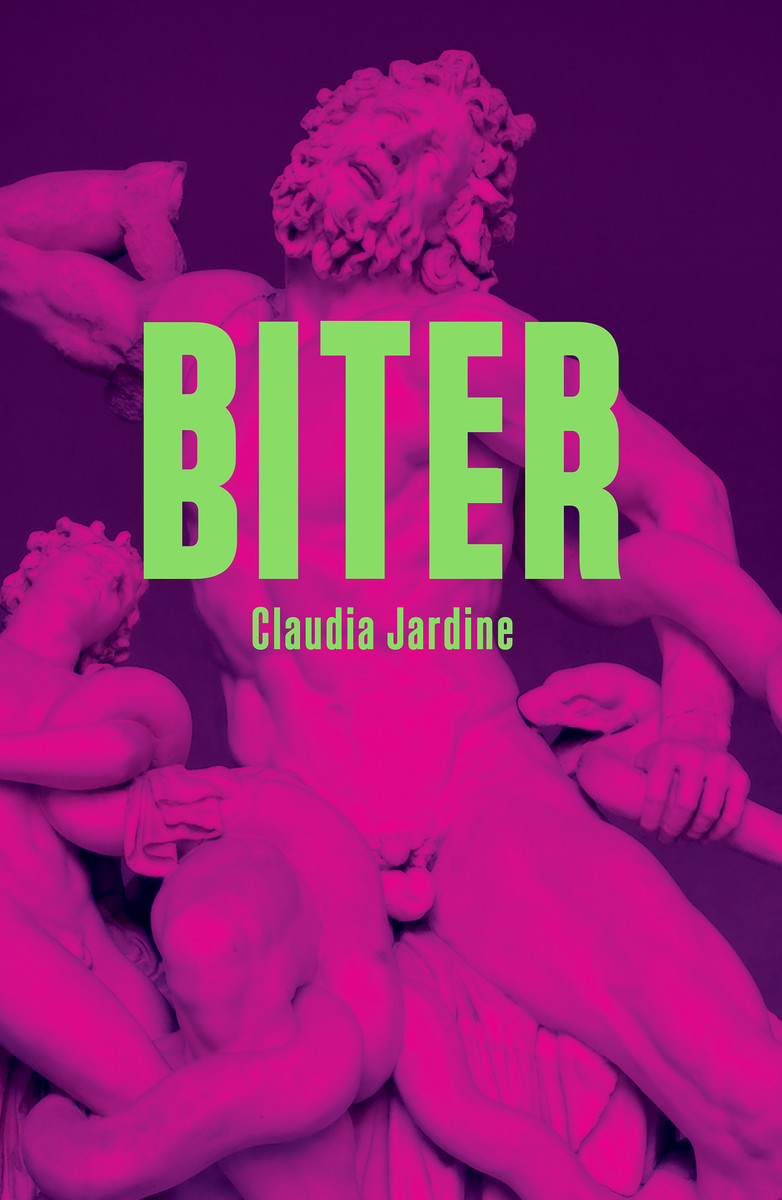

Biter by Claudia Jardine

Auckland University Press, 2023

In her Cordite essay ‘What Blooms Beneath a Blood-Red Sky: A Year in Aotearoa Poetry,’ Rebecca Hawkes, author of Meat Lovers writes:

Poetry is so hot right now, the bright young rhapsodists proclaim (if largely to a devoted audience of each other). Are we just saying, we’re hot now, evidencing the glow-up since high school, the already-anxiety of what it will mean for our newness to fade when we’ve truly emerged and the first-book fetish fades?

(2023)

Good question. Hawkes, queer Pākehā poet and painter, raised in Canterbury and living in Wellington, concludes that no, the poets will always be babes, and maybe she’s right. Poetry is hot right now in Aotearoa and it’s hot in Melbourne too. From my own Pākehā observations across the Tasman in Melbourne, there exists an emerging class of largely millennial writers in Aotearoa revelling Dionysiacally in their post-high school ‘glow-up.’ Claudia Jardine, a Pākehā and Maltese musician, poet, and author of Biter, is also a member of this gleaming cohort.

Nearly all of Aotearoa’s best contemporary writers are alumni of the International Institute of Modern Letters (IIML), based at Victoria University of Wellington, with Tayi Tibble, Chris Tse, Hera Lindsay Bird, Tusiata Avia, Eleanor Catton, and Rebecca K. Reilly among them. The IIML was established as an institute of Victoria University in 2000 with funding from US casino owner, businessman, and Iowa Writer’s Workshop graduate Glenn Schaeffer.

There is a definitive style arising from these IIML peer groups so curiously funded by American casinos (just as the Iowa Writer’s Workshop was funded by the CIA). Tinfoil hats aside, funding for the arts is rarely in perfect accordance with the conclusions we draw from art itself. But it’s worth considering: what interest might American capital have in guiding the flows of poetry in Aotearoa New Zealand?

Aotearoa New Zealand is a tiny country. This is not an understatement. I heard recently that the nation’s gross domestic product is half that of the state of Victoria, so if you think the Australian literary scene is modest, think again. Fellow poet and bookseller Ender Başkan writes in Overland, in his review of my review of Sick Leave co-director and poet (and not NZ politician) Gareth Morgan’s When a Punk Becomes a Spunk (2022), that reviewing is a difficult task.

You are navigating risk, you don’t want to piss your colleagues off, you want to build links, be positive because the scene is small and there are finite organs to publish in or perform with, limited funding. Which is to say that robust debate requires the safety of density—or tenure—a density we might often lack.

(“Poetry can already be free”, 2023)

This is my fifth literary review to date, and I find myself again writing in uncomfortably close proximity to the writers I review. Rebecca Hawkes and Nikki-Lee Birdsey published my first poem in Sweet Mammalian. Hawkes and I are mutuals on both Instagram and Twitter. Hawkes also appeared in one of Claudia Jardine’s music videos. They thank each other in the acknowledgements of their respective books, alongside a number of other IIML graduates.

Heeding Başkan’s caution, I approach this review carefully. In Naarm, or so-called Melbourne, as in Aotearoa, it feels imperative to engage in critical thought about our social standpoints when producing art, and to entertain our own possible investments as a safeguard against the furthering of the naturalised fascism of enduring colonialisms. Başkan prompts further: “Australia is being settled every day. Can anyone who has settled downplay a part in unsettling Australia?” (2023).

Poet and critic Jasmine Gallagher writes that “New Zealand art and poetry is increasingly marked by a form of New Sincerity” (“New Sincerity in New Zealand Poetry”, 2019: 122). She theorises New Sincerity as a cultural reaction to postmodernism, “away from cynicism, irony and scepticism towards a poetics of recovery, hope and sincerity” (2019). I wonder how much this style pertains to the increased access to global publishing afforded by the internet, and the “first-book fetish” acknowledged by Hawkes in her Cordite essay (2023).

The way we express ourselves online has in turn seeped into the way we write offline (if there is such a thing in 2023). There is an immediacy to typing thoughts into a blank field against the blinking cursor of the present, and writing with a pen or pencil doesn’t feel the same. Form influences content, and vice versa.

I can think faster and more freely when I type than when I handwrite, and anything I write on a screen is more widely circulated than anything I say or write by hand. Never before in global history have we been able to overshare so rapidly. Never before have there been so many prescriptions for speed. New Sincerity is a culmination of several world-historic shifts in literature’s form and content, in turn arising from our preoccupation with relentless micro-blogging and the changing conditions of experience.

The rise of internet culture has increased the possibilities for propaganda and power. It has also increased access to publishing, beginning with blogging and arguably never ending, given most forms of social media are essentially new forms of micro-blogging. Perhaps this, combined with the pressures of academic publishing, is where the first-book fetish comes from. In an age where anyone can publish a digital chapbook from their living room, the speed of print publishing makes us impatient.

Where previously poets in Aotearoa weren’t widely read outside of New Zealand, the internet age has provided the opportunity for global readership. Just ask Tayi Tibble, whose poem ‘Creation Story’ was published in The New Yorker earlier this year (2023). Hawkes’ work, too, is set for a North American reception, given her recently awarded (and well-deserved) Fulbright scholarship to pursue a Master of Fine Arts at the University of Michigan.

Stemming from this new reception for contemporary New Zealand poetry is an excitement and a naivety which has shifted away from the cultural emulation of the British empire towards North American modes proliferated in part by micro-blogging and the world wide web. Arguably New Zealand’s most canonised millennial poet, Hera Lindsay Bird’s writing has become emblematic of this IIML style. Oscillating gently between ironic self-contempt and surrealist Tumblr confessional, Bird’s work represents a certain mid-2010s affect which continues to bleed into the tone of young poets in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Opening her self-titled poetry book, The Spinoff agony aunt Bird writes in ‘WRITE A BOOK’:

Now I have a Masters degree in poetry and no longer wet myself But I still have to die in antiquated flowers Does this make me sentimental Well, who’s to judge You can get away with anything in a poem As long as you say my tits in it But it’s a false courage to be so………… modestly endowed And have nothing meaningful to say (2016: 7)

Rebecca Hawkes has something meaningful to say about tits, though she says it a little more sincerely than Bird, with a delightfully perverse flavour of South Island farmgirl sentimentality. Hawkes’ debut book of poetry contains 40 odd poems, separated into two parts entitled ‘Meat’ and ‘Lovers.’ Meat Lovers opens with a visceral conundrum in ‘The Flexitarian’: the poet is trying to be a good vegetarian, but finds herself in “the PORK section,” fondling “sheets of pig skin through their clingfilm” (11; 11).

As far as openers go, this one is queer lady-millennial as fuck: cast as objects under patriarchy, we are perturbed by our own bloody desire for the other. Hawkes discovers a strange horror tucked inside the plastic tray: a nipple, serving as a complex symbol for nourishment and sex, perhaps in service of posthuman mammalhood. The poet tries to cut the nipple out. She scores it and scrubs it raw, but ultimately succumbs to her bloodlust, cooking the nipple and burning her tongue.

What I like about Hawkes’ poems is the generosity with which she allows the reader to witness her coming-to-terms-with. This is a poet who is willing to interrogate the uncomfortable, in equal parts gentle and jarring. This slightly deranged demeanour lends well to a fresh treatment of the problem of meat. ‘Is it cruelty,’ for example, opens with “If the sheep has a broken leg?”, immediately enjambed by a line break which gives way to a series of short, uneven stanzas of questions (29). The poem refuses to look away, finally asking:

If the sheep tries to get up but can’t? Can they walk away from it? Can they still go swimming? (29)

This and some of the other poems in Meat Lovers are difficult to stomach, but that’s a good thing. Poetry can be a portal to the sublime by breaking the little binaries in our brains and providing us with new possibilities. Hawkes does this by evoking a Mid-Canterbury settler posthumanism, drawing us into a truly mammalian bucolic where she blurs human subjectivity against various dichotomies to form her own ethics of ambiguity.

This is one of the most masterful features of the book, and identification with the non-human may well be a feature of an antipodean New Sincerity. Hawkes takes up the position of the dairy cow In “Hardcore Pastorals VII.”, originally published in 2021 as poem “VII.” in Cordite Poetry Review as part of Hawkes’ online chapbook Hardcore Pastorals.

The poem begins, “I am an astoundingly beautiful cow and I know my fate”:

and although you have not yet solved your problem of meat you are something like me I think in kinship you upright wolves you wet-eyed feeling fiends sisters sisters sisters sisters your tiny hearts swelling like bladders take your place in the herd of dying things let us jump all the fences and piss in the rivers yes you already eat of these fields now get down on all fours and graze (53)

While poems about cows are not necessarily new, Hawkes’ particular identification is. She forces readers to examine their existing ideas about the inner life of cows, and challenges these inherited western representations of the animal. The farm is born to sustain the colony, and in the fenced-off paddocks we find everywhere the subjugation of nature by culture in a locked dialectical binary. By going ‘hardcore’ on the pastoral, Hawkes helps us to ask: is the colonial pastoral ever really about cows and wheat, or is it merely power masking its own illegitimacy through romantic obscurity?