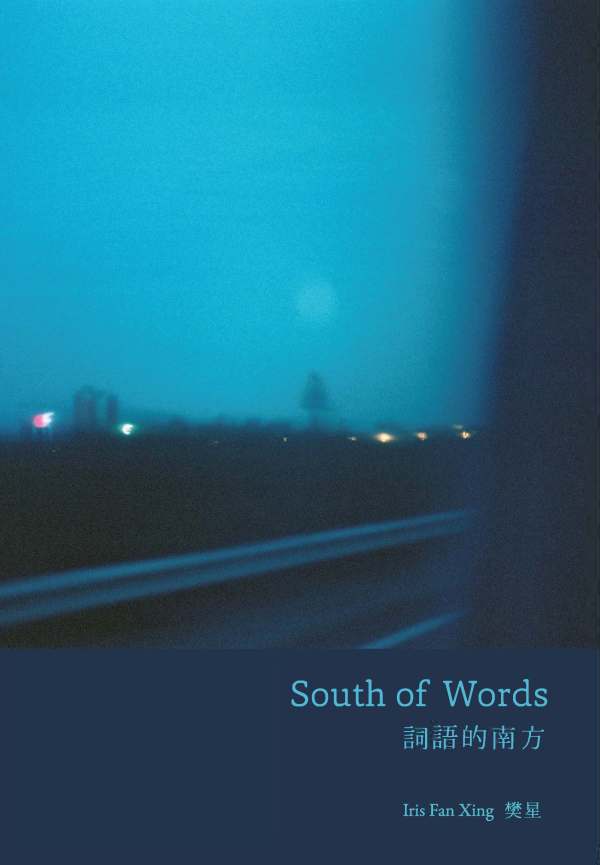

South of Words by Iris Fan Xing

South of Words by Iris Fan Xing

Flying Island Books, 2018

Christopher (Kit) Kelen has described Iris Fan Xing’s South of Words as ‘not translation’. The intersection between English and Chinese Mandarin lies at its heart, reflecting Fan’s converging identities across settings and cultures. Her publisher, Kelen identifies that readers’ engagement with bilingual poetry can be limited by our evaluation of translated works predominantly by their faithfulness to the assumed ‘original’ product, often regarding translation itself as necessarily an act of ‘watering down’. Fan has previously subverted this notion in her debut collection, Lost in the Afternoon (2009), which was intended instead as a conversation between parallel texts, capable of greater richness and imaginative value in tandem than as a standalone works.

South of Words operates in a similar manner; as a non-Chinese speaker, I am acutely aware that my reading of the collection is incomplete. Nonetheless, it is this prospect of her multilingual poetry that allows Fan to represent cross-cultural identity on its own, authentic terms, while offering a uniquely nuanced experience to readers, particularly those belonging to the author’s diasporic communities. In the same way, South of Words does not convey Fan’s relationship to Australian and Chinese cultures as discrete influences, but rather in their cultural synthesis.

The most overt representation of this occurs in the titular poem, which lies at the centre of the collection as a division between the English and Chinese sections. In ‘south of words’, the languages weave in and out, with English words in black text and Mandarin in white, together on a hazy, grayscale photograph. As the poem progresses, its background fades closer to black until the English words are almost fully obscured and the Chinese characters are starkly clear. This transitive quality serves to exemplify the collection’s emphasis on journeys, tenuously mapped out with direct and indirect references alike:

the music will never be lost 又比如在黃昏的鄉間路上 透過飛馳的車窗 if you know how to listen sit under a jacaranda 瞥見一匹桉樹下的馬 豐滿垂墜的腹部 when it’s blooming let it play out loud 懷著一輪橘紅的太陽

The dialogic relationship between English and Mandarin is echoed with Fan’s thoughtful paralleling of physical locations – not by means of seamless, perfect comparisons, but through the sincerity and occasional disjointedness of personal perspective. This can be seen in ‘smog’, where Perth and Macao share common ground within their respective opposites:

don’t know why but parting always reminds me of drifting clouds maybe because I know that Xü Zhimo poem embarrassingly well and you’ll agree with me a seaside town like Macao presents the best kind of summer cloud generous in volume and almost tangible the same kind in Perth in winter

Similarly, ‘after Hayashi Fumiko’ elicits an unsettled emotive response by drawing connections through—and in spite of—elements of disconnect:

living in a country on the condition of a visa is a visa is a visa […] and our cat lost one of her nine lives to a passing car but we know in Chinese eight is the lucky number

In this sense, the bleeding of cultures into one other allows Fan to subvert the notion of a perfect metaphor in favour of a perfectly subjective metaphor. Memories are conveyed in their esoteric honesty – closer to the odd, internal logic of a child trying to rationalise the world, than the platitudes of an adult attempting to neaten it. Fan’s metaphors feel uniquely authentic in their refusal to be overwrought—or sanitised in a social vacuum—for the sake of universal relatability. The result, however, is relatable in its affective significance as a reader. Speaking a truth that is equally personalised by direct confession and subtle contextualisation of Eastern and Western influences, contemporary and mythological figures, and multilingualism, Fan produces work that is layered with interpretative nuances, but can still be appreciated at different levels of depth. This allows for a diversity in readership of Chinese and non-Chinese speakers alike, and both casual and academic readers of poetry, without alienating those who lack specific contextual knowledge and may simply enjoy the thoughtful intrigue of Fan’s language choices.

South of Words demonstrates the subjective merit of its intertexts in their capacity to enrich traditional modes of evocation. The relationship between experiential and referential elements allows for an undiluted representation of the self that is not confined to the East or West either in physical location, nor language, nor self-identity. This is also depicted frankly in ‘love it or…’:

love it or write it in your language ignore grammar – tense and gendered nouns mine for the sound of storm in clouds for the image of a peninsula and its reflection on the sea where evening tides race like ten million octopuses love it or reverse the mirror a waratah is still a waratah a frangipani a frangipani but a word is not the same word love it or live it

Not only does this poem portray an uninhibited self, but it intertwines the entities of place and person. ‘love it or…’ also emphasises the metapoetic urge to create one’s own rules and write in a manner of authenticity that is self-defined in expression. In ‘Canton holiday’, the wider implications of valuing subjectivity are also conveyed as a protest against detached, officialised views of history:

she said when representing history you need to defamiliarise does she mean we should see through the eyes of that stray cat?

The poignant simplicity of these words is undercut by the power of their suggestion, simultaneous calling on the reader’s internal and societal awareness. South of Words ultimately feels like an exploratory journey of re-familiarising, where the self is as elusive and evolving as its physical settings, and histories are personalised within experience itself. In Fan’s poetics, while nothing is immune to change, nothing is quite devoid of familiarity either.