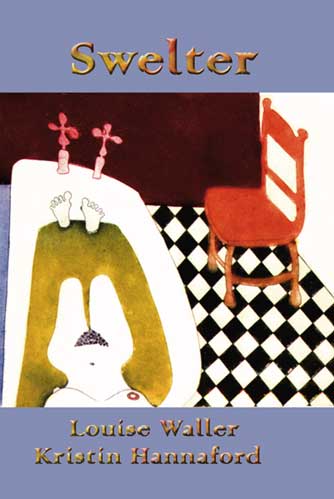

Swelter by Louise Waller and Kristin Hannaford

Swelter by Louise Waller and Kristin Hannaford

Interactive Press, 2004

It was with anticipation and trepidation that I approached Swelter, an audio and text CD compilation of Louise Waller's Slipway and Kristin Hannaford's Inhale. At first I expected some type of multi-media explosion – always a hit-or-miss affair, as most multi-media 'experiments' entail artists getting overly excited about something old-hat in the 'new' commercial sphere. My concerns were exacerbated by the work's New Age publicity blurb (full of words like 'family', 'nature' and 'life-affirming') that filled me with fear and led to my leaving the CD untouched in a drawer for weeks.

However, after listening to and reading the words, I could see that both poets have found their own types of beauty. While Waller's work is tightly bound in the shroud of isolation and loneliness, Hannaford's is smooth and sensual. Yet sadly much of their work is immediately stuck in a mire of 'performance' and clich?© and I battled long and hard to discover and appreciate their beauty.

I listened to the audio as I read Swelter on the screen to experience the work in its entirety, but little did I realise the damage that could be done by the great Australian drawl. Even now, I am haunted by that droning voice punctuating each syllable of “For you this wide arm of friendship lifelong” (from Waller's 'The Fourth Whiskey').

I once felt that poetry, like song, was more than just a digital medium for our analogue minds and should be read aloud. But today there is a culture of the self: everyone wants a 'voice' and tries to get in touch with their inner-troubadour. The modern performance of post-modern, computerised, over-produced poetry is symptomatic of this trend. It might give the arts-funding bodies a warm fuzzy feeling inside to know that there is a poet reciting in a forest somewhere – and there are many great performance poets out there – but the industry as a whole would do honours for itself if nine out of ten poets would learn to shut the hell up and stick to writing. I do not wish to scapegoat Waller and Hannaford for a disease of the entire Western world, but their readings do them little justice.

This reading was compounded by a typically Australian content that bears little relation to typical Australian life. It is steeped in our peculiar blend of academia-bound pretension with its desperately insincere folkish twist. Almost all of Waller's poems start with a quotation by someone else, and her pieces in particular are riddled with intertextual literary/artistic allusions:

I suffered two accidents in my life. One in which a streetcar knocked me down. The other accident was Diego.

– Frida KahloFor the two Fridas debut

you paint hearts, the veins join

It seems you have just used scissors

to take a small sorrow out

Two open heart Fridas

who hold handsBlood spoils in a pool on the folds

of your white dress

Beside you, the wild she is spared

Keeps the Diego souvenir in her fingers

It looks like a stone

to guard against forgetfulness(from 'The Frida Dialogues')

I fear that I am maybe conveniently unleashing a torrent of invective built up after studying poetry for five years straight. Indeed, there is beauty in the collection. Stripped of the more cliche conventions, of the audio track and of my own personal stylistic gripes, there are diamonds in the rough of Swelter.

There is, for example, something sensual and tactile in Hannaford's 'Inhale'. The need for the reader to hold a degree in English is generally absent, and in its place there is a sense of location, time, emotions. The audio recording is still best avoided, and stylistic clich?© abound, and much of the content is still alien to me; but it does not feel so alien. It feels apparent, existent, there before me, touching me:

this day, our children, the minutes of our lives together.

Let me have this possession. Don't movebut you do, as you leave by the grey sky

sinews unravel and I am undone.(from 'Possession')

There is a tension built by the repetitive 'don'ts' that accentuate the physical force described, but this tension is not released satisfyingly – like the act of sex cut short, without orgasm – as the pleas are left unheard. The poem remains allusive, but also devoid of the literary pretensions and in their place are emotions. By giving us a tangible sense of place and physical sensuality, the emotions are made real, imminent, and somehow universal.

The pure physical act – and its incumbent emotions – is explored in 'All This Kiss' which portrays what seems to be a story of innocence lost. 'Lips Sore From Too Much Kissing' continues this exploration, but this time the experience is inverted, and Hannaford becomes a voyeur of young love:

oblivious to this crowd of coffee drinkers

who, as they observe, reach under steel tables

holding hands as they pass-

remembering swollen body textures

and love's complete first bliss

This loss-of-innocence theme is pushed further in 'After the Shower', which discusses border disputes in mother/child and woman/boy relationship. The discussion could almost be seen as Oedipal; yet this is not Greek tragedy or Freudian theory, but visceral and concrete humanity. The mother has knowledge of sexuality, the son none, and she knows that when he becomes aware they will both lose their innocence. But since she knows this, it is already lost. As with Eve, the loss of innocence comes not with doing but with knowing. There is something almost disturbing here, but that only comes through because the mother is worried about it being so, and because she knows it will one day happen. Once again a tangible, and sensual, feeling of place belies a deeper and highly charged meaning.

There are many problems with Swelter: the audio tracks are close to a waste of time – somewhat akin to the director's commentary on a DVD, of interest only to fans – and my cliche alarm sounded manifold klaxons. At the end of the day, a slimmer volume would have been welcomed (maybe one millimetre instead of two?). But both authors have something to say, and they do offer different perspectives.

A person is more than their check-box answers to the National Census and poetry is more than 'content'. To treat being a woman with a family living in Queensland as a genre (as is often done) should be left to the domain of the marketeers, sloppy academics and arts-grant committees. Waller's is hardest hit by such off-putting 'data' and clich?© and I found myself almost fighting her poetry for meaning and connection, although I suspect there is something there, albeit hidden. Hannaford, on the other hand, places us in a physical and sensual environment, and her poetry hence comes across as relevant and meaningful. I found it touching; and a reader not turned off by terms like 'life-affirming' would be all the more touched by her work in Swelter.

Andrew Craig is a twenty-four year old editor of the Flinders University Writers' Club Journal and has a coronary incident planned for August, 2010, which he is currently working on.