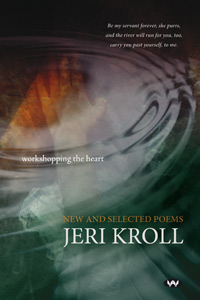

Workshopping the Heart: New and Selected Poems by Jeri Kroll

Wakefield Publishing, 2014

Workshopping the Heart brings together poems from Jeri Kroll’s five previous books of poetry, with thirty or so pages of new poems and the opening chapter of a verse novel. Her distinctive voice – lyric, tough and spare – is evident early. Take the poem ‘Genus and Species’, in which the speaker recounts visiting her grandfather as a young child:

He kissed hello too hard. Tasted pruney.

Stared a lot. At me.

(‘Genus and Species’)

Kroll’s concision and her talent for arresting imagery is apparent here and elsewhere:

A white lady opened her wound,

licked it shiny.

Slow hiss. The door.

(‘Genus and Species’)

Internal rhyme is used to particularly striking effect in the poem’s resolution, which is reminiscent of the childhood poems of Gwen Harwood and Elizabeth Bishop:

Grandfather bent like a weary dog

trying to mouth his prey.

He raised a limp paw as I flew out the door

drawing his good eye and father behind.

(‘Genus and Species’)

The book’s middle section focuses on the domestic and familial. Hamlet presents the world as a prison ‘in which there are many confines, wards and dungeons,’ similarly Kroll employs a deft conceit to tell us:

Every family is a life sentence.

The only things that change

are pictures on the prison walls

and the view from the window.

You make your peace with the system,

learn to play off the inmates ...

(‘Parole’)

Her lyrics on motherhood are compelling and unflinchingly sharp – never collapsing into sentimentality. There are moments of tenderness, in which the speaker is besotted with the beauty of the infant:

His penis floats like a white-tipped asparagus,

his tummy swells like a melon.

(‘Bathtime’)

In other places, the demands of the present interrupt meditation and love battles with darker impulses, as the speaker struggles to retain sanity:

But today you came close.

I could easily have done you in.

The ambulance would have been too late

to save what’s left of my martyred patience.

(‘On watching a sleeping child’)

Such battles often end in a hard-won synthesis of dutiful, yet jaded, resignation:

… my voice rolling in like friendly fog

making you invisible till dawn.

The blind raps us awake

and sun begins to burn me off,

letting you confront the clear-cut day.

(‘Night Waking’)

In later poems the son’s childhood and his absence in adulthood are movingly evoked. I can recall few poets, in Australia, who have written, so consistently well on this theme.

The poet’s mother is central to the final part of the selection, as Kroll describes the effects of Alzheimer’s:

My mother is floating out to sea

without buoy or boat. She smiles as she drifts.

(‘Water to Water’)

The literal sea that the poet’s mother lives beside is now ‘dolphin-smooth’ and ‘[n]othing worth comment breaks the skin.’ These lines articulate a terrifying banality: dolphins – with all their mythical associations – are unremembered and unseen, nothing breaks the skin of the water and the speaker’s viewpoint fails to break the surface – fails to communicate.

Even the word sea means nothing Because she becomes it.

‘My mother’ later becomes ‘the mother’ – as if she were shedding personhood; her degeneration increasingly harrowing for the speaker, who retains the consciousness the mother has lost:

The mother is a still pool,

waiting for me to ripple with my words

I stir and stir.

(‘Exercise 1: Similes’ from ‘The Mother Workshops’)

Aging and death are revisited in thirty pages of new poems. In ‘Skin’, ‘furrows … remind us that the past is getting closer’, and soon skin ‘is all we can remember’. The new work has a similar epigrammatic quality but these poems have not been through the same winnowing process and the weakest lack the interest and strangeness of metaphor so consistent throughout the rest of the collection.

The book concludes with the opening chapter of Vanishing Point, a forthcoming verse novel. If Kroll maintains the lyric intensity of this taster it is sure – as this New & Selected is – to be a great success.