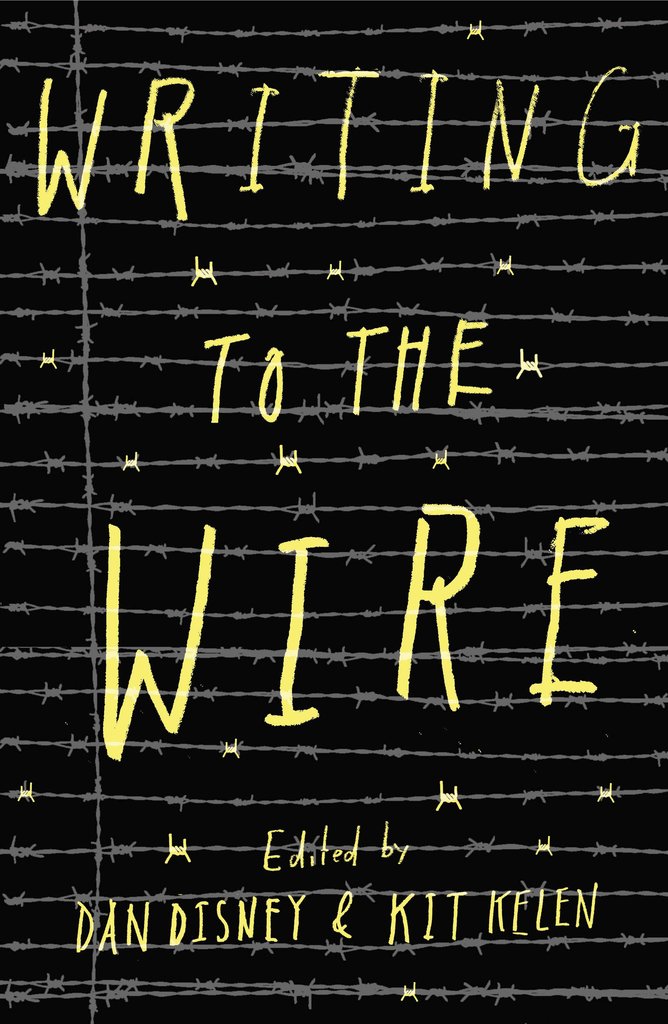

Writing to the Wire, Dan Disney and Kit Kelen, eds.

UWA Publishing, 2016

Hannah Arendt clearly noted it: a dog with a name-tag has a better chance of surviving than an anonymous dog. She also noted that the alleged protections offered by legal and moral rights – human or otherwise – would only be made available to those who did not need them. The right to have rights would be stripped from the rest; they would be consigned to the worst. And so it came to pass: governments around the globe, wearied by the difficulties of politics, turned themselves into servile machines whose only raison d’être is to help deracinated multinationals to extract as much surplus as fast as they possibly can from the peoples and places of the earth. Politicians of every stripe are now the sworn enemies of the people that they allegedly represent, preferring to torture children than risk being put out of office by an irritable corporate goon.

So Dan Disney and Kit Kelen, clearly horrified by the situation that they outline in their introduction to Writing to the Wire, have commissioned a truly diverse range of Australian poets and asylum-seekers to call us back to our responsibilities through verse. It is clear that this is an issue that should bring us together against the entrepreneurs and exploiters of human misery, and it is surely not nothing that so many well-known writers have answered their call. One exemplary bio reads: ‘Rachael Briggs immigrated to Australia from the U.S. Became a citizen. People in camps deserve the same opportunity.’ Yes they do.

Yet many of the contributors are not marked by their publications and other accomplishments, but only by an initial: ‘A. is from Iran’; ‘A. is a Hazara boy from Afghanistan who has been incarcerated in Australia’s immigration detention network for more than two years’; ‘B. is a young man who has been incarcerated in Australia’s Manus Island detention camp for the past 27 months. He chooses to withhold his name.’ Several have even lost their initials altogether: ‘Name withheld’; ‘anonymous.’ Such a severing of bodies from names is symptomatic of dictatorships, not democracies.

Whether anonymous or notorious, all contributors are concerned to speak as best they can about such a deleterious state of affairs, evident from even a glance at the alphabetised titles: ‘drone illuminations’, ‘Drowning Inland’, ‘The Duty of Punishment’. As Samuel Wagan Watson writes in ‘No entry anytime’, which has Muhammad Ali’s famous anti-imperialist and anti-racist boutade ‘No VietCong ever called me a Nigger!’ as an epigraph: ‘Restraining orders come natural to me…this isn’t my country unless a federal court deems it so. I’m not welcome here and I’m not welcome there …’ Or there’s Ali Alizadeh, whose ‘Who’ speaks of ‘the degradation of the political to policing’. Or, as B. describes in ‘Night’:

Every thing is worse than our nightmares –

torture and despair.

Bring me the night.

At this point, there is no difference between poetry and testimony: the true speech of the witness, which goes beyond the brute facts to touch upon what cannot be experienced without misery and dissolution; the address to others who were not there, who may not have eyes to see or ears to hear, but whose existence provides a (minimal) hope that there is more to the world than unjust incarceration, primitive accumulation, and murderous rapaciousness. Writing to the Wire does not provide a context for aesthetic evaluation, but for the transmission of testimonial gestures of justice.

We know the fiscal costs of one great Australian corporate and governmental cabal: nearly $10 billion dollars to date to keep refugees incarcerated by private companies on foreign soil. That this indefinite incarceration of innocents is now the preferred alibi for governments to transfer taxpayers’ money to private hands – and so impoverish their own polities, their welfare and education systems, as if that impoverishment were the very essence of the salus populi – is a kind of epitome of Orwellian double-speak and double-think. An epitome of contemporary charity, too, given that the sadistic sociopaths who chuckle and sneer on Q&A as if they were simply discussing the qualities of snuff, constantly congratulate themselves on taking the hard moral decisions for our benefit. Nathan Curnow’s ‘Reply to a father from a Federal Member’ takes up precisely what W H Auden would have called the ‘elderly gibberish’ or the ‘gushing drivel’ of these irredeemably corrupted personages: ‘Explain to your kids / that you can’t be specific / in the interest of national security’. When you live in a world where reporting on a crime is considered worse than committing one, it becomes ever easier for the culprits not only to evade responsibility, but to turn the victims into the true criminals. Sigmund Freud points out that, since that every individual, no matter how timid, submissive, or law-abiding, remains a potential threat to the masters’ rule, the ultimate telos of government must be to ensure perpetual peace through universal mortification.

It’s perhaps noteworthy that, despite the embittered irony evident in a number of these poems, nobody proffers a satire on the order of eating refugee babies or selling them for medical experiments, like Jonathan Swift on Irish impoverishment, or Monty Python on indigent Catholics. Perhaps that’s itself a sign of how bad things are, that the extremity of radical literature may be too uncomfortable to sustain in the ambit of these actual atrocities, that the concentration camps are simply too calculated in their evil to permit any too-extravagant an imaginative response. Still, I was queasily struck that several poets here almost seemed to compare their perceived lack of attention as poets in Australia with indefinite incarceration behind razor wire, out of sight out of mind on client islands – but there you are. It’s a reminder that the wire doesn’t simply divide us from each other, but runs within us, dividing our own actions from themselves, our affects from our effects. To that extent, we ourselves have become a ‘Trash Vortex’, to use Felicity Plunkett’s disturbing phrase.

As Julian Burnside QC writes in his foreword, taking up an image of Vladimir Mayakovsky’s: ‘I hope that all Australians who read these poems will be inspired to start hammering our government for a refugee policy which more honestly embodies the true values of this country.’ I hope so too. Yet I also fear that poetry itself isn’t really politics; it may even be the opposite of politics. Power politics is often the committed enemy of poetry. Still, even such politics must retain an attenuated link to the same language which poetry deploys. Opening and opposition, then: where there’s language, there’s life. Is that enough? Think of Bertolt Brecht’s refrain from ‘The Infanticide of Marie Farrar’ (in S.H. Bremer’s translation):

But you I beg, make not your anger manifest For all that lives needs help from all the rest.

There are many ways to read Brecht’s plea, including that anger is a signal of despairing impotence that can trick you into moral self-regard rather than political action. At the very least, then, you should read this book, before hammering your Federal Member.