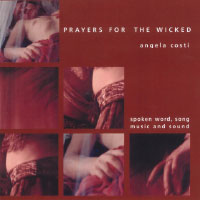

Prayers For The Wicked by Angela Costi

Prayers For The Wicked by Angela Costi

Sunshine and Text Studio, 2005

To begin with, it should be noted that Angela Costi's Prayers For The Wicked – a CD of “spoken word, song, music and sound” – tells a tale of Greek Australians, deals with many traditional topics, and occasionally features Greek dialogue; and I myself am not Greek, and know none of the language. Some would argue hence that I am inappropriate to review this work, but it must be remembered that much of the potential audience of this work – and surely they should be taken into account – will not be of Greek descent, thus not possessing the bilingual luxury that I too lack. In this context, I am as qualified to review this as the next person – after all, the contexts that the language is used in within this work alone speak volumes. Also, Greek is a beautifully melodic language, and, to use a very bad musical analogy, you don't need to know German to bang your head to Rammstein.

To the “work” at hand (for uniformity, I'll refer to it as a “work”, as opposed to poems or a recording or whatnot). Costi, at the launch, called this a “creative closure on a decade of poetry and spoken word, from 1993 to 2003”. Consequently, perhaps, it's a very developed and mature work, the product of living in wildly varied moments coupled with creative retrospection.

Most significantly, unlike most examples of this genre, it tells a causal narrative, a story. It begins with the character (rather obviously, presumably Costi) as a child, describing a day with her grandfather Pappou. The local reference in the work is instant – indeed the first word spoken in the work is “Epping”. Somewhere in Epping, grandfather and granddaughter are out collecting artichokes – or at least the former is, while the latter is not exactly zealous about it, “wishing artichokes would go back to Pappou's foreign land”. While hacking away at the heads of these plants, Pappou suffers an injury by accident, “the knife his embattled betrayor”. While the narrative doesn't say whether this incident was fatal, it was obviously serious – “Pappou's song hobbling into prayer” – and it appears to have made a lasting impression on the child. From a psychological point of view, and especially in the context of the narrative, it appears to be the beginning of the character's questioning of mortality, belief and faith.

From here the story fast-forwards to the (subjective) moral quicksand of nightclubbing. For the next three tracks (from a total of eleven), the character struts her stuff in this quagmire of moral decadence, hedonistic freedom and spontaneous sexuality – “my tongue is a-pummeled into passionate pulp”. Despite the freedom, however, the underlying feeling of these nightclubbing tracks is undeniably the wanting to become part of a whole, to feel belonging, and never quite achieving it – “My feet, they want to dance E, but they shuffle like dope”. She may be feeling the moment, but she doesn't seem to belong in it. The tracks reek of confused exclusion, of being there yet not there, as if the environment is merely fulfilling the purpose of track three's concluding refrain – “filling the silence of lust”. Or perhaps track four puts it more succinctly, describing being lost in:

The song, the dance, the boy, the girl,

the moon, the mirror, the view, the skill,

the smack on the cheek, arse or brain.

and concluding with the line “we all get loose, in the lost”, implying that everyone there, not just her, is lost. Track five waves the nightclub universe goodbye in a short instrumental flutter, to be replaced with Greek music – beautifully and crisply recorded, like the rest of the CD (more on production values later). With the shift from doof to Greek comes, finally, a feeling of acceptance:

She is as Greek

as I am Turkish

I accept her invitation

of hip bone and song

we dance the same history

and our seduction is fierce.

The use of the Greek language, as in this track, is often sung, and works wonderfully within the context of the work. As mentioned earlier, the Greek tongue is very melodic, and even if one knows no Greek, here it flows naturally with the English narrative, serving to reinforce both the culture and atmosphere of the text.

This aspect is particularly effective on one of the work's standout tracks, `Grey Sundays and Unanswered Prayers'. This track paints an effectively realistic portrait of a working class Greek-Australian family battling with its own faith. It talks of drinking, menial jobs and events such as:

The loss of half week's pay on a poker game

with greedy brother-in-laws,

the loss of wife's respect when she searched pockets

the next day.

And yet the fire of hope thrives on, perhaps ironically, within the next generation; for instance, when the child wants to wipe the flicked Holy water from her face, the father says no – “He wants the Holy water to stay with her as long as possible – she still has a chance”.

The curiosity in the child's character is well expressed, as she “thinks more than she talks, imagines more than she prays”, and “crosses herself from left to right, when her Dad's not looking”. This curiosity manifests itself in her yearning to see the sections of the Church where “girls are forbidden”, a realm which her father – eventually and significantly – permits her to enter.

The title track is a mixture of self-searching and self-actualisation; or more specifically, of the character becoming aware of her own beliefs (“I realise that I am the Daughter and I have my own liturgy”), and wondering where they fit into the pre-established order of belief structures. For example, she is aware that her hunk-like impressions of Jesus – “I could see him in suede, a goatee, a nose ring, even in leather outrebelling James Dean” – would be seen as heresy to those with “closed-legs and locked-ears”.

The pre-established universes of dance/rave clubs and churches mingle when one of the character's friends analogises the two institutions – God being the DJ, the priest the manager etc. Yet while the simplistic divinity of both seems clear to her friend, uncertainty still thrives within her. Sitting in a church, she reflects:

I search for any glimpse of myself

– half an eyebrow or an ear?

Nothing of me shines back

like the mirror ball of squares

all you can do is stare into glazed reflection

and hope for acceptance

then wonder why you need it?

The story of the last track, `Grandmother Maroulla's Liturgy', is one of both acceptance and displacement. It brings the work to a conceptual full circle, if ending on a note that's up to interpretation – much like life. It speaks of people far away from the “ancient Greek gospel”, from their homeland. The words depict a character (the grandmother), that isn't entirely compos mentis, yet “pole-vaults expectations to accept a maturity only the blessed reach”. The simplicity of this track's short tale offers a potent emotional conclusion to this collage of mental maturation, especially while interlaced with the refrain –

In the well of silence,

echoes of childhood,

reminders of destiny,

creep back.

The overall effect is ethereal, surmising that despite all of life's noise, destiny still underlies it, if only one cares to listen. Perhaps this was one aspect Costi hinted at during the launch, mentioning “the Cypriot-Greek world of contemporary myths” – or perhaps this is simply a universal message.

All of the above has been a simplistic synopsis of the work's story. I'll conclude with some comments on the text and music in general. Costi's singing vocals are noteworthy unto themselves, and her narrative voice is suitably rhythmic and dynamic, although occasionally they lack the passion the text can demand. The text is colloquial and insightful, very much up to Costi's usually high standards. Some words will be known to those familiar with Costi's work, for example some of the material on Prayers For The Wicked appeared in her anthology Dinted Halos (Hit & Miss Publications, 2003). From a literary and artistic point of view, perhaps the most commendable aspect of Prayers, as mentioned, is that it forms a narrative whole. It has the beginning, it has the progression, and it has the resolution. It does paint a picture of emotional and spiritual growth, eloquently and concisely, within only eleven tracks, a venture in which so many artists – poets and musicians – try to do and fail.

But it is important to remember that this does only consist of eleven tracks – clocking up just under an hour – so don't expect a War and Peace, Aeneid or Odyssey. But it isn't meant to be; as a work, it's more akin to Pink Floyd's The Wall, in the context of a half a lifetime of emotional rapids being represented by a mere hour or so's worth of material. In this context of sweeping, essentially indiscriminate editing, it succeeds in its aims admirably. It also makes it very accessible.

Some comments on the music/sound, which was performed/sampled by Peter Davis, Duncan Graham, Paul Huntingford and Rex Watts – beautifully played and recorded, and, more pertinently, appropriate. In much of the poetry-put-to-music material I've heard, it seems that the music/noise/whatever has been more pasted on as an afterthought at the last minute, rather than taking context into account. One of the best exclusions of this was Steve Smart's 2003 EP Diatribe (Bootfull Audio), yet even those poems could have featured pretty well any genre of music, and not strictly the electronic backing tracks that featured on the recording. Not so with Prayers; the music and sound effects are the text, lending themselves to eachother with atmospheric ease. In this context also, Prayers succeeds where others have failed.

This work has the potential to have a wide appeal; it's slick, eloquent, concise, with professional production values. But more significantly, as an attempt at merging the mediums of spoken word and music, with Prayers For The Wicked, Costi has set somewhat of a benchmark for other local writers to aspire to.

Ashley Brown is a Melbourne-based writer, having had reviews, articles, interviews and poetry published in many Melbourne literary haunts. He is a currently postgraduate student in Literary Studies and holds a BA in Arts Business.