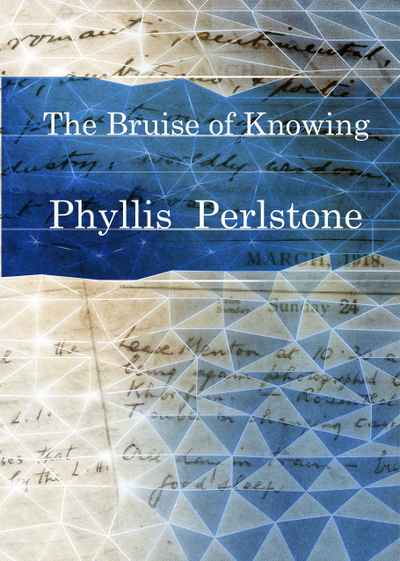

The Bruise of Knowing by Phyllis Perlstone

The Bruise of Knowing by Phyllis Perlstone

Puncher & Wattmann, 2019

The Bruise of Knowing is Phyllis Perlstone’s third collection of poetry from Puncher & Wattmann, and arguably her best to date. It tells the story of Sir John Monash, highlighting themes of ambition, power and warfare. A talented engineer and commander, Monash’s progress was conflicted by religious bigotry, the rise of feminism, and a growing awareness within himself of the devastation wrought by war. But this is not just history, although the Australia and Britain of Monash’s lifetime are vividly recreated. Perlstone selects revealing episodes of strength and weakness in her protagonist, interpreted through poetic devices that allow the reader to experience undercurrents well beyond the series of events. At the same time, this anecdote is counterpointed with several parenthetic poems drawing the writer-researcher into the framework and underlining current concerns with the encroachment of the built environment on the natural.

Part 1, shifting back and forth in time, deals mainly with the nineteenth century. The collection begins with the poem ‘Two Incidents as Engineer …’ in 1901. In this poem, the language is deliberately hard-edged and precise in its description:

the bridge twists concrete bits break off the water's splash, the crashing pieces the slow time of gravity's next is like glass in an accident the traction engine tips and falls

The impact is heightened by concrete, enjambed lineation and broken syntax, brief lines directing emphasis to where the poet wants us to pause and absorb. In this poem, also, the reader is given early notice of Monash’s ‘greatest regret’ for the needless ‘loss of life’:

stilted, his mind's stall word's remove him from the moment − as if he could speak for the pall of ends in the air, of being stopped of waiting

By contrast, in poems such as ‘In the new Barangaroo Reserve’, we are offered Perlstone’s perspective on the resultant feats of engineering:

As in Sydney now, walking in the city that some dreamed we would wish for, the heights and bridges built − though sometimes we want to descend from these intersecting frets strutting steel, sharp-cut graze of concrete blocking the intimacy of trees

She follows this with ‘Barangaroo’, where her evocation of the natural world is uplifting:

In this place that's retrieved today from industry at Barangaroo this recreation of a ruined shore buoys now sway again, against the white trailed water of a ferry's wake

Monash married Victoria Moss in 1891. Three months later, diagnosed with suspected tuberculosis, she was convalescing with her sister in Beechworth, Monash travelling back and forth by train from Melbourne. As Perlstone notes, ‘The Law and its outlaws / mixed in Beechworth’, none the least the infamous Ned Kelly. She describes the settling of power that happened here:

Poor equipment like Kelly's makeshift headgear − dark imprisoning iron − more than masking armour − Nolan's later icon.

A disputed mythology has grown up, linking Monash to Ned Kelly, as in Peter FitzSimon’s 2014 biography of the bushranger. Perlstone has eschewed including any such incident but uses the iconography with metaphoric force. She introduces an attested meeting between Kelly and Monash’s father (in Jerilderie) and suggests Monash’s later interest in the Kelly Gang. In an ekphrastic poem ‘The Slip’, based on a well-known painting by Nolan, the horse’s fall from a ‘precipitous’ height is perhaps reminiscent of Monash’s own trajectory.

In this first section of the book, Perlstone begins to show the uneasy relationship existing between Monash and his wife Victoria (or Vic). This, she mostly develops through interpretation of photographs and artworks, with an impressive sensitivity to bodily language and gesture, as in the poem ‘1898’:

Vic's full skirt, jacket and jaunty hat free-stand on her, almost and match the double-breasted suit constricting Monash

The rift appears more strongly in ‘An Early Photo of Monash and Vic’:

looking in separate directions they have the same upholding of themselves for the camera to be seen, yet between them their expressions dilate with defiance, expose opposite views […] And what is inner with Vic is there by her mouth her dark hair and dark dress the high collar around her neck and head, prevent any premature list or lean into Monash's plans

The continuing disintegration of their relationship is interwoven with related themes including the growing rise of feminism and husband’s and wife’s opposing responses to it:

He's avoided Vida Goldstein, feminist, 18 years old. Monash announces she is "all too self-possessed and affected". […] Quarrels start He should be "the master" their future should be shaped so he can succeed.

Once again, the poet’s voice interposes, interpreting and responding to emotional overtones, as in the visually evocative ‘Damp Window in the Rain’:

umbrellas passing under the fig tree leaves hold the patterns like a slide-show each walker giving way to another on the wet black pavement the tented colours screening shapes traced like under-lit shadows without the sun Abstrusely a sight I turn to reflecting on Vic watching the hesitant configurations. It was her time of not wanting a life rushed through Hardly one to seize