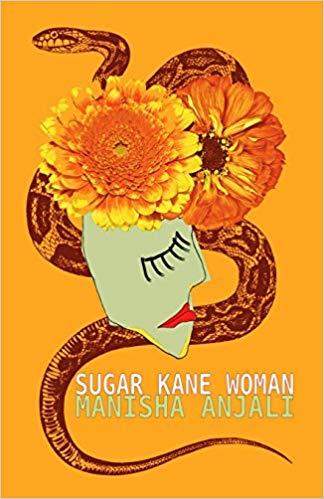

Sugar Kane Woman by Manisha Anjali

Sugar Kane Woman by Manisha Anjali

Witchcraft Press, 2017

Towards the end of the nineteenth century and after the turn of the twentieth, colonial British rule brought indentured Indian workers to the fertile shores of Fiji. The colonisers hoped to boost the local sugar cane industry without antagonising local Fijians, and so boats filled with indentured labourers from all over India were trafficked to the island for a life of servitude and abuse.

Such is the bleak background from which Manisha Anjali’s colourful debut, Sugar Kane Woman, published through Witchcraft Press, comes alive. Snakes, hibiscus and tobacco smoke twist up from the pages of this mid-length collection. We are drugged and danced through generations of Anjali’s women as they work to find their identity, the instinctive connections between each other, and the sand between their toes.

The poems begins with ‘all woman is a snake’, a poem that at first asks specific traits of woman (‘all woman who has brwn spot … all woman who has long black hair … all woman who has red dot on her skull’), then takes them away from her again, repeatedly shouting ‘ALL WOMAN IS A SNAKE’. This generalisation so early on might set the reader on edge, implying a certain set of requirements for woman-ness, the inescapability of the serpentine and its connotations of the untrustworthy, sly and slippery. Anjali follows this opening up, though, with a collection of poems discovering the unique in her women, avoiding a proscriptive consideration of gender.

She swings from the woman general to the woman specific with grace, narrativising the unique existence of the Fijian Indian woman in the whitewash of the global patriarchy, and imagining what it might be to break free:

how lovely it was when we burnt our saris & swam naked with tiger sharks in the white cyclone the garlic from beneath our fingernails mixxin’ with saltwater i was no longer a wife but a fish swimming under the stars of mo(u)rning (‘3 wives’)

In ‘marriage advice from two kaiviti sisters in a nadi bakery’, the cultural and social politics between Kaiviti (indigenous Fijians) and Indian Fijians becomes apparent through dialogue. The implication is clear – a Kaiviti woman thinks that ‘you marry fijian ok. / fijian good. indian bad.’ Cultural assumptions and generalisations leak in on top of uninvited commentary on the right weight and shape for a woman to be when seeking a husband: ‘here you take two cream buns / you too skinny lewa / fijian dont like skinny’.

Anjali makes distinct choices to own the language in which she writes this collection. Non-English words are not italicised. Sugar cane becomes sugar kane (which might reference Marilyn Monroe, or Sonic Youth, the Velvet Underground; or it might reference none of these), brown is reclaimed as brwn—in the same way the spelling of blak in some Australian Indigenous writing takes back the positive power and ownership of the word—and your is always yr, which can be a divisive stylistic move in itself. This ownership, as well as the non-capitalisation and, I assume, intentionally inconsistent punctuation throughout, feels youthful despite its generational retrospectives and magic realist time-travel.

Indeed, it can be difficult to place the woman subject in Anjali’s timeline – whether the poem be from the perspective of the poet, a mother, a nani (grandmother), or otherwise. The collection might have benefitted from delineated sections, or chapters, to establish the generations in structural form – thus borrowing from Marquez not only the magic realism of the oppressed, but the generational storytelling elements of the master’s prose work. It may be, however, that this uncertainty is precisely what builds the sense of continuity, of a layering that cannot be unlayered. In any case, ‘my mother’s dreams are not my own / ’, insists the voice in ‘girl shaman’. So, ‘who is the owner of these little brown shoes?’

Poems like ‘3 bloods’ work to gather the generations for the reader and make the connections clear, and often painful:

mamma’s mamma kicked my mama dunked her head in 3 rivers until the bloods came because mamma’s papa was a drunk & a cheat so my mamma paid. my mamma beat me blind broke my two cheeks & scratched my two eyes until the bloods came cos my papa is a drunk & a cheat so I paid. when I am a mamma and I have a daughter and her papa is a drunk & a cheat what will I do to make the bloods come?

‘The bloods’ are removed from the natural association of menstruation and pushed into a generational history of domestic abuse. As foils to love and warmth, violence and exploitation are constant, frequently masculine presences in Sugar Kane Woman, writing a reality that surfaces in the kava- and alcohol-driven furies of Anjali’s men:

he moon drunk. he kava shine. he smell like piss and smoke my pots and pans he throw broke on the floor or our the window (‘moon drunk kava shine’) when he is angry he will piss on his red plastic chair on the front porch just so he can watch me clean it up & anybody else walking past can watch me clean it up too. (‘housegirl blues’)

And though there is some anger and resentment in return, more often the female presence in the works is simply self-assured, imbued with ‘magick’, marigolds, coconut, kava. I am reminded of the strength of older women I have known, who have learned not to break after years of almost breaking despite the pressures of oppression, assault, medical mistreatment, unhappy marriage and other injustices.

I was born in the field & made to work the same day

with the blood the blood running down my legs

the blood the blood running down my legs

yeah I moved mountains in my dreams.

I don’t care for sunsets

I’ve seen them one hundred and one times. (‘sugar kane woman’)