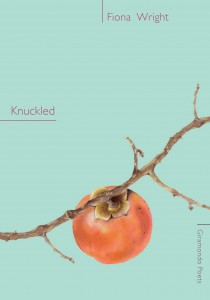

Knuckled by Fiona Wright

Knuckled by Fiona Wright

Giramondo Publishing, 2011

Knuckled is the debut collection from Fiona Wright, and can I just start by saying that ‘knuckled’ is a great title for a book of poems? It’s a word that’s easy to understand, one that immediately brings images to mind (hands, fists, gnarled trees, walking-sticks) but also one that you don’t hear that often. It’s also a fabulous word to say out loud over and over again. On first read, my thoughts were that this was simply another collection of lyric poetry: a bunch of measured short free-verse observations (some wry, some earnest) and descriptions of things (a frangipani, cutting open a persimmon, bushfires, bus rides in Sri Lanka), one observation per poem, one poem every one-to-two pages. An interesting collection: diverting but unremarkable.

On second read, though, I liked Knuckled much more than that. The poems are strong, clever, tight. They feel like they’ve been edited and rewritten until their focus is much clearer, until any first-draft excesses that may have existed have been stripped back considerably. It’s solid stuff – the kind of poems you want to talk to people about, read out loud to them.

This is a poetry charged with image and emotion that leaves enough unsaid to allow the reader their own responses, but which is detailed enough to be unambiguous. In ‘Mona St’, Wright cleverly and evocatively describes station wagons as ‘herringboning’ one-way streets. In ‘Something Has Happened to Katie’, there’s a line that talks of ‘sheeny-dressed girls who slip / from bar stools to flexed biceps’. In ‘My Sister Doesn’t’ she describes hot days sitting in old cars as she and her sister become ‘the pork that’s roasting / out of season’. ‘Cannula’ describes ‘jelly solid as arteries’. ‘Kinglake’, a poem written in response to the bushfires that devastated Victoria in 2009, sees Wright describing the burnt-out bush as having ‘a silence / eucalypt and lunar.’ ‘Treehouse’, a poem about the not-entirely-enjoyable nostalgia of furtive adolescent fumblings, perfectly describes the light from neighbours’ houses barely illuminating naked skin as two young people fool around in a cubby house.

Here and there some of the elements of Wright’s poems don’t quite work. The occasional metaphor or simile clunks down onto the page or leaves awkward questions in the reader’s mind. What’s dangerous about Wollemi pine? How can a mind be ‘emulsive’? What does it mean to be ‘tubular as a dissection’? Does a sunburnt, peeling nose really look like a prawn? These are minor quibbles, though, and easily forgiven or overlooked in the face of streets herringboned by station-wagons and artery-solid jelly.

Of the four sections that Knuckled is divided into, ‘West’ is my favourite. It feels vital and contemporary, which befits a sequence of inner city portraits. The poems here are funny (name-checking librarian porn, pointing out how hard it is to look sexy on a beanbag, apologising to the children of poets on behalf of their daggy parents) and attentive (noting smaller details like succulents in gardens, bins that are merely buckets, boxes of washing powder stacked on footpaths, torture rehabilitation clinics next door to delicatessens…).

The other sections of the book are ‘Bruising’, a deft collection of – for lack of a better term – nature poems (eels, trees, fruit, bushfires), ‘Inheriting Colombo’ (a poetic travelogue contrasting Wright’s travels in Sri Lanka with her grandfather’s war service there) and ‘The Waters’ (a more loosely themed section that touches on floods, drought and beach holidays, among other things).

It may simply be due to its slightly more intangible (or slightly broader) theme, but the poems in ‘The Waters’ don’t feel like they hit the mark as often as those in the other three sections. There’s still some crackers, like ‘Old Jindabyne: Flood’, about the ghosts that inhabit a drowned town, and ‘The Last Family Holiday’ with its bemused look at a father’s relationship with his adult daughters, but Wright feels somehow less present in these poems than she does in the other sections.

This is one of the potential risks with dividing poetry collections into thematic sections: the segregation is sometimes arbitrary, and there may be poems in a section that don’t fit the ostensible theme very well – that may in fact not fit any of the designated themes. This can sometimes prompt the reader to look for thematic connections between poems that may not actually be there, which can weaken the impact of an otherwise well-written poem.

That’s just another minor quibble, though – it’s worth noting that one of my favourite poems and the first in the collection to inspire me to dog-ear the page for future re-reading, ‘Old Jindabyne: Flood’, comes from this section.

In this poem Wright imagines the abandoned town of Old Jindabyne at the bottom of Lake Jindabyne, and speculates on what might still live among the submerged buildings, serving up dry-land/bottom-of-the-lake juxtapositions like tidal hills hoists and cabbage-weed gardens before concluding with:

They say that soggy shadows of ourselves still walk on the old roads stand in queues in banks, buy groceries in plastic bags, soft and bulbous as jellyfish.

The image of the jellyfish plastic bag is immediate and vivid, a worthy counterpart to the swirling, dancing plastic bag used to such good metaphorical effect in the movie American Beauty.

Also dog-eared for re-reading was ‘Lithgow Panther’, part of the ‘Page Three Girls’ sequence, a modern retelling of the old big-cat-escaped-from-the-circus urban myth, full of tension and danger as the poem’s protagonist is ignored by the police and bureaucrats and mocked by shock jocks, all the while the panther getting closer and closer to her. The fear that this situation engenders is reflected well by Wright onto her sinister description of the touring circus that the panther has allegedly escaped from. This cleverly taps into the universally unsettling nature of circuses (or is that just me?), full of ‘the smell of damp straw / iron bars and facepaint’, a description that she complements in the following verse with a line about ‘the crying clowns, the brown bears in jester hats / visiting Lithgow’.

The collection concludes with two pages of explanatory notes at the back, providing some context for the few poems that use found text (the ‘Page Three Girls’ sequence and ‘Persimmon Poem’), and defining some of the Sri Lankan words used in ‘Inheriting Colombo’, as well as a couple of other obscure terms used throughout the collection. This section is mildly helpful, but I was left wondering if the information they contain might not have been better incorporated in the poems themselves, or even, in the case of the identification of the quoted texts in particular, left unremarked upon altogether (for example, it was perfectly clear from the context set up by ‘Colombo: Day Leave’ that kassipu was a kind of alcohol – being told this in the notes section felt redundant).

Again: quibbles. Knuckled is a fantastic first collection: smart, confident, engaging and inquisitive. Any poet couldn’t help but be happy with this as their debut.