Since 1972, satellites have circled the earth, collecting images of it and sending them back to be catalogued and examined. Conventionally these satellites are called landsats, sometimes EarthHawks. Landsats tend to have a 16-day orbit. Most of them only last for three years. But Landsat 5, it lasted for 29 years, meaning it circled the earth over 150,000 times, sending back over 2.5 million images. Landsat 5 captured Chernobyl three days after the nuclear disaster. And the oil wells that were lit on fire in Kuwait as the Iraqi forces left. And the tsunami in South-East Asia. But it did not just capture large historical events. As Landsat 5 circled, forests burned down and then became deserts or parking lots. Flowers bloomed and died and bloomed again and died again. Rains came and went. As did floods and hurricanes and droughts. Ice caps melted and 11 new emperor penguin colonies were birthed.

When Ella O’Keefe writes about landsats in her poem ‘Landsat 5’ she points to ‘our unspeakable / patterns of use, inhabitation’.

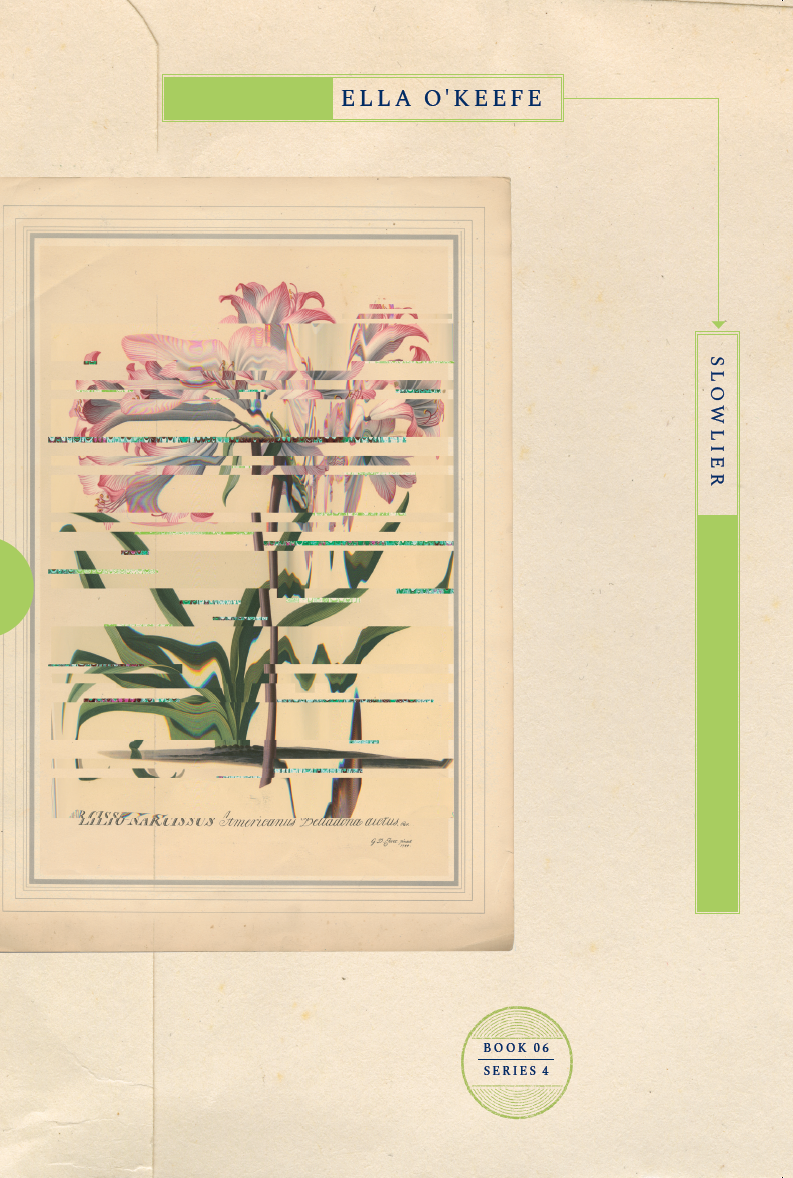

O’Keefe writes with a landsat aesthetic. She uses juxtaposition so that fragments of the world float by, bumping up against each other. The poems travel, board planes, catch the bus, have a lot of walking to do. Unsurprisingly, things are often seen through a screen. In one poem, there are ‘whole corners for televisions / that burst from brackets’. In another, ‘flat screen jellyfish inhabiting conversions’. In another, workers ‘hold phones / up to the hidden moon’. Sometimes these same screens broadcast the riots of our time and are ‘a ledger / of brutality that stays near’.

In ‘Landsat 5’, O’Keefe speaks of ‘the uneconomic fraction’. The same year Landsat 5 was launched, the USA privatised satellites and their data was turned over to a commercial vendor. Image prices skyrocketed. And the vendor, as commercial vendors do, only collected data that it could sell. The rest became the uneconomic fraction. And these images disappeared. Our unspeakable patterns of use made even more unspeakable.

Poetry might best be understood as a corrective to this, and as itself an uneconomic fraction. In O’Keefe’s poems, these fractions are the waste products of capitalism. She, for instance, attends to the bottom of a Hackney canal, one filled with ‘150 years of Britain’s industrial history’. At other moments ‘pink smoke’ floats by, a reminder of ‘how much of our domestic scene / is held together with compounds / squeezed from tubes.’ Often O’Keefe is concerned with how products are created. She begins one poem with a moquette rug, notes its tenderness and give thanks to its ‘soft passage’, but then as it continues she notices the ‘livestock prices’ within it, next the rug being made, the yarn being ‘loaded into the matrix’ and the poem continues on, reminding us that mockado, a sort of fake velvet, was made to conceal. The poem ends with an allusion to courtly poetry. But it is not just a rug that experiences O’Keefe’s keen eye. So too a cartouche, an AlkAway, a scratchcard. And through these items, O’Keefe builds a complicated world, one that attends to the uneconomic fractions, the waste rock, and turns them into the poem, or ‘crystal form data-mining in the apricot light’.