John Mukky Burke – one of my favourite philosophers – is the most underrated poet in Australia. His usual lacerating intelligence and empathy are here in this sensational collection, but ‘exuberance’ is the word that keeps occurring to me as I read. Burke is a poet who, in maturity, has shed many masks and is the better for it. He revels here in the godawful, funny, earthy business of being alive on Country today. Sex and death dominate (‘when a cock approached a cunt’), with detours down any manner of kangaroo pads. And there’s bold new authority in his voice, too:

Who said something about someone somewhere somehow caring for a sparrow? Didn’t you fucking know that?

‘My Sister and I Get Our Mess of Pottage with a Small Kid Dead on Mr Boynton’s Double Bed’ tells of a stark rural childhood. There is zero pathos and no dogma; rather, a blunt country voice, reporting:

No one ever said to me not to go there, not to see, not with the house full hushed with crying, and the dead child frozen, laying on the bigger bed and in the back room, congealing porridge in the kitchen spoilt with tears and snot, yours cold, mine not. I left you there, and could stare at only death right in the arse.

Similarly in ‘Warts, an Extract’, an old man reflects on his life, then and now: ‘No toilet, no mattress, no primus, no kero … And now I can type on computer, Jesus!’

Burke has dialled the dryness up to eleven, and by Christ it can be funny. As a young teacher, stuck, Burke got his kids in the Northern Territory some Kiwi penpals:

One girl over the Tasman wrote something that ran almost exactly like this: There five people in my family: me, my mum and dad, my younger brother and my grandmother, but she’s dead at the moment.

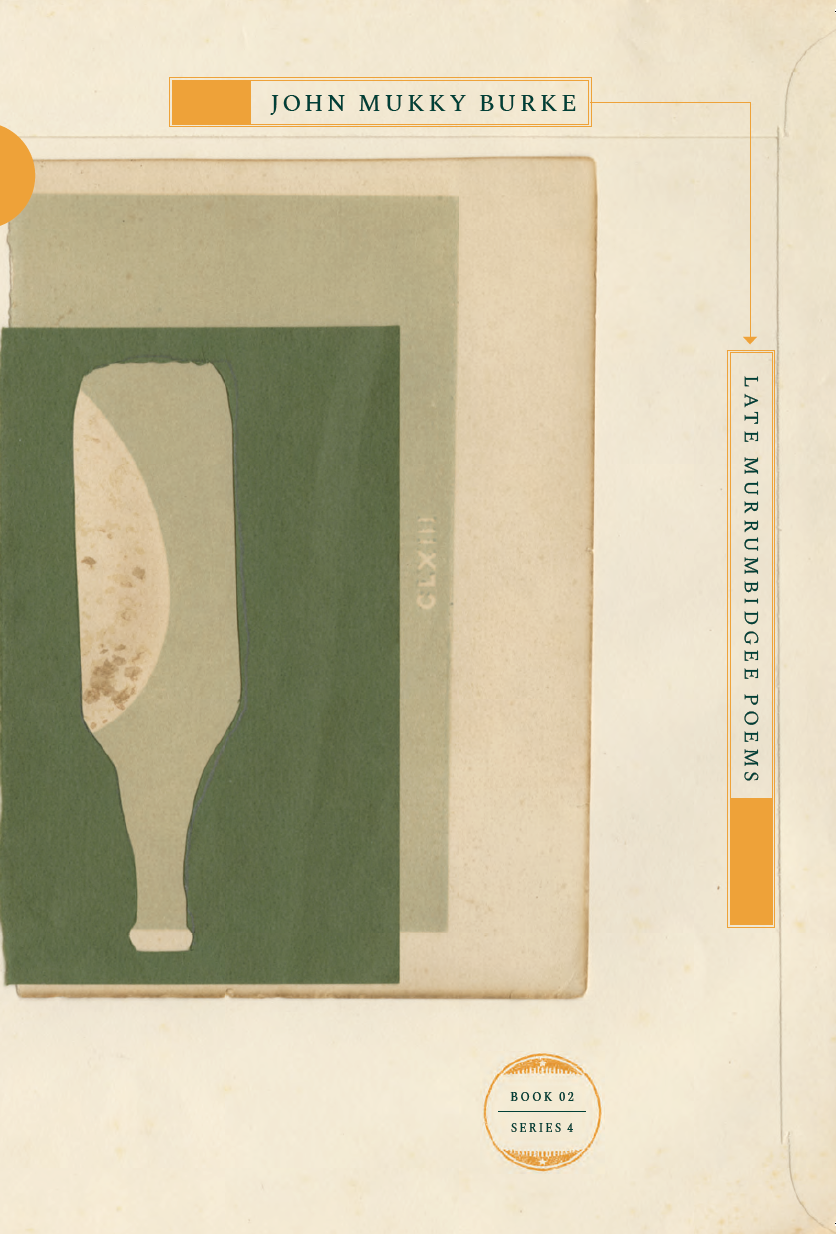

There is always death, of course, and worse, for ‘we people who have walked at midnight have seen a great delight of pain’. But death and pain are no more than components of the great game. Proudly Wiradjuri after battling his white skin for years, openly gay after decades of closeted torment – Burke’s pen crackles with energy in Late Murrumbidgee Poems. I busted out laughing at the excoriating ‘Happy Wagga, an Overview’.

The collection covers vast territory, from the insufferability of colonial explorers (‘Cook Was Not an Anthropologist’) to experimental work in the voice of a religious petrol sniffer. I was delighted to find included here my favourite Aboriginal poem, ‘Poem for the APEC Ministers’. In ‘Zac’, Burke speaks lovingly as an elder to a younger Koori man (‘with the blackest eyes’) struggling with life and in denial of his aboriginality.

The natives of Turtle Island tell that, collected, poems and stories are medicine bundles. They feed us and give us courage. This collection is just such a medicine bundle, but it’s more than that. It’s a kangaroo skin scraper passed to us from the hand of a master wordsmith and intellectual giant.

Hold it close.