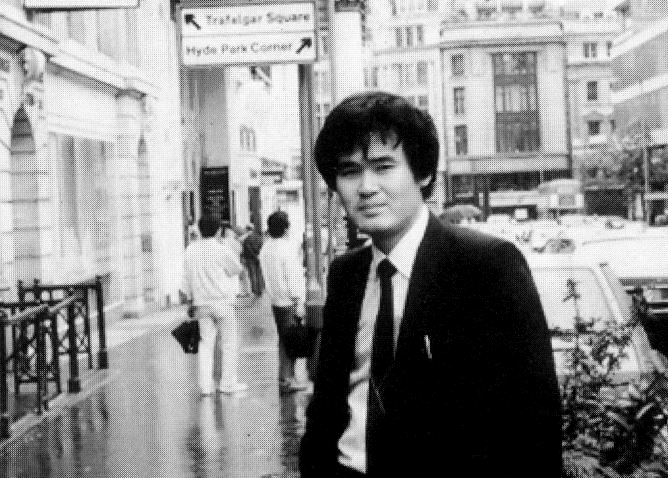

Photo from Beyond the Horizon

Gay/Poet/Korea – these were the first three words I typed into a search engine prior to undertaking the Cordite/Asialink residency in Seoul, South Korea. I’d typed these three words out of genuine interest in each – both singularly and collectively – but also out of a kind of frustration, having first consulted the section for gay travellers in the Lonely Planet guidebook:

In a country like South Korea, where social pressures to conform to a rigid standard of ‘normality’ are intense, it’s not surprising to learn that Koreans are intolerant of homosexual behavior. Lack of tolerance is hardly unique to Korea, but what is interesting is the lengths to which Koreans will go to deny, dismiss or rationalize the existence of gay and lesbian relationships. For most of mainstream Korea, homosexuality is a) non-existent or so rare that it’s hardly worth mentioning (so don’t); b) a freakish crime against nature; c) the manifestation of a debilitating mental illness; or d) a social problem caused by foreigners.

This section goes on to suggest that things are changing in South Korea, though it fails to state these changes as categorically as it does opposition to them. Perhaps this failure highlights the great disparity between a thing ‘changing’ and a thing having ‘changed’ but what of the subtle negotiations taking place daily for those that would benefit most from change?

And so, the search for more information.

Gay/Poet/Korea – it is not lost on me that with these three words I might well have been searching for myself, attempting to locate myself in a new context, a new country, but in the end the search produced Gi Hyeong-do.

‘Gi Hyeong-do: A Misunderstood Modern Gay Korean Poet’ was the heading. An article with a concise overview of his short but eventful life, from his impoverished beginnings, his father’s cerebral palsy, the death of his elder sister, his academic success and time as a journalist to his death at the age of twenty-nine in gay sex venue. A venue more often than not euphemistically referred to as a ‘movie theater’.

Three of Gi’s poems – ‘Grass’, ‘Front of the Bar’ and ‘Dead Cloud’ – accompanied the article. With the first four lines from ‘Grass’, my interest peaked:

I have an appendix but I don’t like eating grass I am a poor excuse for an animal

Whilst in Seoul, I sought out the translator of these poems, Gabriel Sylvian, in an effort to further understand the significance and impact of Gi’s work in South Korea, the subtle negotiations inherent in the translation process and the assertion of homosexuality as a fundamental and formative reality for Gi, a reality that shaped the narrative of his life and work.

Terry Jaensch: Gabriel how and when did you first come into contact with Gi Hyeong-do’s poetry?

Gabriel Sylvian: The first time I heard Gi’s name in connection with gay poetry was seven years ago, at a gay bar called ‘Contact’ near Hongik University Station. It was a karaoke bar (actually ‘dive’) in the basement of a run-down building a few blocks from where the Commission houses its grantees. I’d just arrived back in Seoul after ten years and was trying to get some sort of political project underway. After researching during the day, I’d go alone to the bar and hang out. Small groups of customers would come straggling into the bar after midnight for their second or third round of drinks and, just by chance, I got to know some poets and one or two teachers. One guy, a Korean literature teacher at a high school, mentioned Gi’s name in passing. ‘Gi’ is a rare family name in Korea, so at first I misheard it as ‘Gim’. It was a few days before I figured out his name, surprisingly written with the Chinese character for ‘strange’ (laughs). His work wasn’t hard to find since his Complete Works had come out five years before. I just borrowed the book from the library and started reading.

TJ: When did you first decide that you were going to translate his work?

GS: Once I got the book, I began with the shorter pieces, trying to get a quick sense of his style, themes, something. One of the shorter poems appearing near the beginning of the collection is titled ‘College Days’. It describes a college student, a loner intellectual, reading Plato on the school steps, or hiding in a grove of laurel trees at the rear of campus while shots sound in the distance. I checked the poet’s bio and saw he was a Yonsei student.

The shots, of course, refer to the clashes between student demonstrators and riot police that were a regular feature of campus life during the Jeon Du-hwan era. I’d lived just a five minute walk from that grove in the mid-1980s, in a Western-style house for international students near the university’s back gate. History professor Milan Hetjmanek, now at SNU, was teaching at the International Division that year, and Richard Krebill was our de facto house mentor. So I knew that grove, the old red-brick structures in the background of Gi’s graduation photos, and that same horrible sound. Yonsei University was a hotbed for student activism then. Classes were frequently cancelled due to tear gas explosions. None of we foreign students were psychologically prepared for it all. It all came back to me with that poem. The poem affects everyone who was a student in Seoul at that time in the same way, I think.

Gay cruising in Seoul was like a darkness within a darkness. You felt steeped in criminality at all times. Nobody really trusted anyone else. You had to keep your bag close to you or it would get stolen (laughs). Gi’s poems are dark and at first I just thought he was a depressed poet, maybe gay, maybe not. Later, when I found out through an article that Gi had died at the Pagoda Theatre, things came together more clearly to form a composite picture. So early on, by virtue a few coincidences in our backgrounds, it was easy to feel that I should try to translate his work. From that point I started thinking about how Gi’s life and art might be integrated into a political project.

TJ: There seems to be a great deal of conjecture surrounding the suggestion that Gi Hyeong-do was homosexual, even though he died in a gay cinema. What is your take on Korea’s inability, despite this fact alone, to even raise it as a question?

GS: The call for ‘proof’ is a central problem that the project has had to grapple with. The intellectuals in the gay community have always claimed Gi as one of their own, but I have sought proof. While translating his poems, I read everything Gi wrote, including essays and fiction, and every academic article, criticism and reminiscence written about him I could find. There’s not that much, really. Maybe less than one hundred articles. Except for one essay appearing in a book on postmodern Korean culture published in Europe, I found no mention of Gi’s sexuality anywhere in print.

TJ: That sounds extraordinary, but I’m guessing it was no shock to you?

GS: Well, who would ever expect to find a study of any Korean poet’s sexuality, gay or straight, or even poetry about sex? There were, of course, wild exceptions to the rule. Poet/novelist Ma Gwangsu, popularising Freud and free sex back in the 1980s, was arrested and tried by the Korean government on morals charges for, among other things, including scenes of homosexuality in his work. Then there was poet/novelist Jang Jeong-il in the late 1980s and 1990s. Similar charges were brought against him, too, by the courts in the 1990s. Tellingly, Gi did not shun, but showed an active interest in both writers. This is important background information to consider when thinking about Gi and same-sex sexuality in his literature. As for Gi the man? In the various recollections written about Gi by his colleagues, and in the testimonies of those whom I’ve interviewed (none of whom, by the way, seemed to know Gi very well – he seems to have been very private and is described as a loner), there are clues that stand out to the gay investigator and which support the theory of a same-sex orientation.

TJ: Can you elaborate on this a bit further, or highlight some of these ‘clues’ for us?

GS: Everyone I’ve met who knew Gi personally, for example, describes his speaking style as very effeminate. His taste in clothing was also consistent with an effeminate man’s tastes. He was known for his fastidiousness, meticulousness. Also, his family dynamic fit the classic stereotype of strong mother / weak father. Now in his prose, Gi once or twice mentions his own weakness, his ‘effeminacy’, in building relationships with women (though I think tellingly, never in his poetry, where the object of desire or address is ‘the friend’ or ‘you’) and this has been suggested by some as ‘proof’ that Gi loved women, negating the possibility of his being a homosexual.

First of all, anyone familiar with the Korean gay community – even today – knows that Korean gay men marry and have children. Some desire a conventional family, and sometimes this desire stems from social pressure. Marriage and family is what has been expected of all able-bodied men and in many cases, not doing so would mean being stigmatization as a social failure. From my interviews, I’ve found married gay men love their families but they feel this is not enough to satisfy them emotionally and sexually. How much more was this the case in the 1980s, when Gi was writing, than today? Before sexual politics.

The gay-straight dichotomy we so ‘naturally’ internalize as gay men today is blurred where identity politics has not taken root. This is especially true of men who were of Gi’s generation and older. So it is naïve, a mistake, to expect Gi to conform to present-day notions of a self-consciously queer poet with a solid sexual identity structure. Again, it bears repeating that gay Korean poets writing in the mainstream today, in 2011, are still not at liberty to publish same-sex poetry for their public readership. None of the poets I met at ‘Contact’ or elsewhere did. They didn’t dare try, nor any of their gay poet friends. So we certainly could not expect Gi to have done so. Directly, that is.

Pingback: En la semana del Orgullo, dos poemas de Gi Hyeongdo – islas en la red