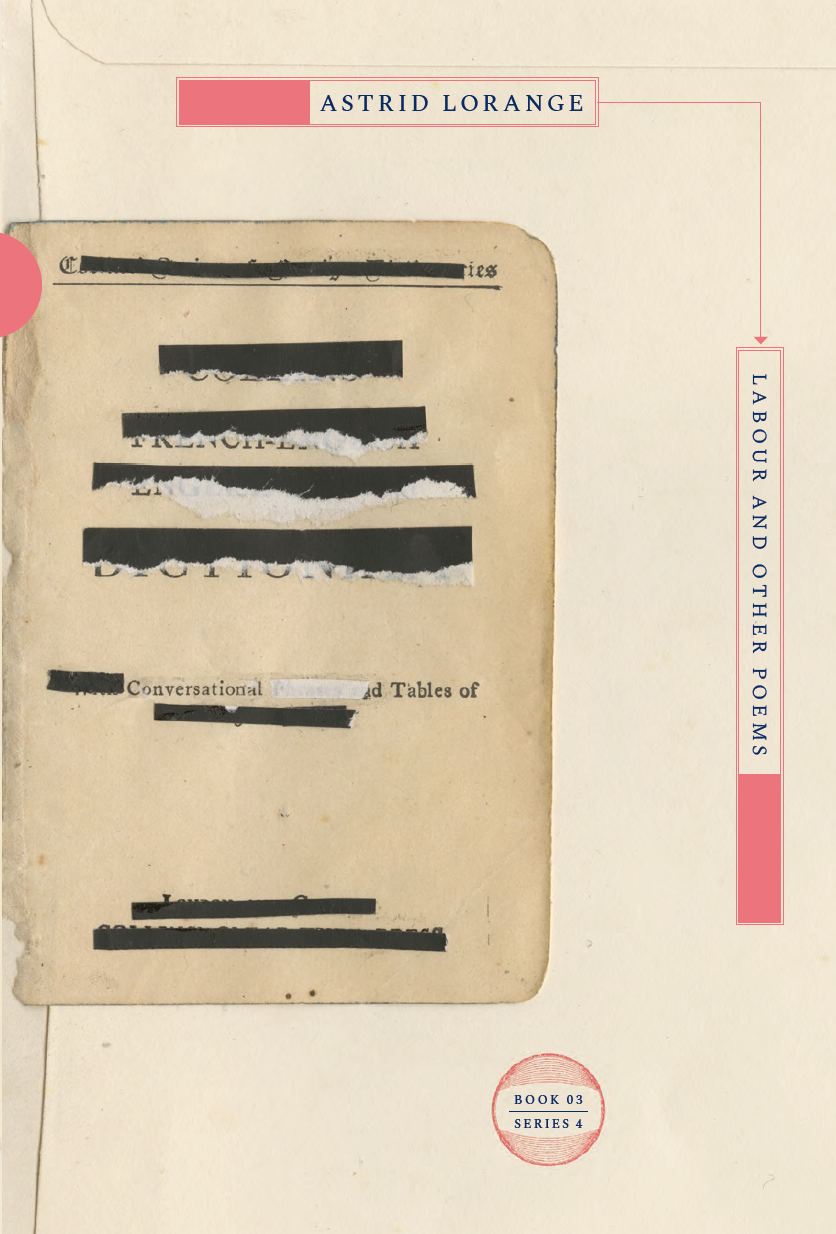

This book is titled Labour and Other Poems. Just as Astrid Lorange speaks of building a poetics – intensive and intentional – as a way of perceiving the world of relations in their shadow, every poem here requests an attentiveness to the multiple relations of our lives, to the entwining of senses and references.

Labour is a word that enters English from Old French, where it not only means ‘task’ or ‘exertion’ but ‘hardship, pain, affliction, misfortune, suffering, distress.’ Labour is a word that cuts across all traditional divisions of, well, labour, insofar as it designates at once childbirth, ‘the sublime and violent history of reproduction,’ and hard yakka, the foundation of production. Almost always and everywhere, Lorange reminds us, this labour is extorted and expropriated: birth slavery and wage slavery and slavery tout court.

In The Human Condition, Hannah Arendt makes a distinction between labour, work and action. Each corresponds to a basic condition of being-human: labour corresponds to the biology of the body, to the condition of life itself (‘nature’); work to the unnaturalness of human activity (‘culture’); finally, action takes place specifically within and between the plurality of human beings, for being human is not to be human like any other human (‘politics’). Labour concerns life and the life of the species; work, the production of things that persist beyond mortal lives; action, the production and place of history itself. Arendt famously identifies natality – the entrance of the new life into the world – and not mortality – being-towards-death – as the motor of all values in their constant revaluation. Labour, as Lorange writes, both with and against Arendt, the labour, never finishes.

This too is part of the labour of poetry. ‘Toast for Friendship’ concerns secret organisations and their politics of friendship. Like the CIA, the Nazi jurist Carl Schmitt considered that the essence of the political was the power of deciding on an exception, and that such an exception entailed the formation of friends and enemies. What does toast mean here? Stéphane Mallarmé wrote a famous ‘toast’ or Salut, a poem of greeting and celebration to his poetic friends. But toast is not only a form of delicious fire-charred bread, nor a public salute to outstanding persons or deeds, but a demotic idiom meaning ‘destroyed, decimated’. In an Australian context, think how ‘Toast’s penumbra of significations – grains and alcohols and vast aggressions – are correlates of the invasion of the wheat eaters. And the remnants are everywhere: take ‘Ex’, which proposes a kind of molecular pheromonology, of abiding if often imperceptible micropolitical affects.

Oddly, labour is also a collective noun for a group of moles, e.g., ‘a labour of moles’. In Hamlet, Shakespeare’s eponymous hero acclaims his father’s ghost in such terms: ‘Well said, old mole, canst work i’ th’ earth so fast? A worthy pioner! Once more remove, good friends’. Labour, law, life and friendship are thus linked. This image of the old mole that burrows unseen and unknown, clandestine, beneath the soil of the symbolic, impressed the German philosopher G W F Hegel, who invoked it to characterise the labours of world spirit; in Hegel’s wake, Karl Marx picked it up to designate the labour of revolutionaries in The Eighteenth Brumaire; for her part, Rosa Luxemburg used it to propose the slogan ‘Imperialism or Socialism!’ These moments are also part of Lorange’s labours:

Patriots, says the CIA, should be wary of poetry: it can be revolutionary but not even feel like it. It’s time we started really feeling like it.